Artifact Highlight: Iwo Jima 80th Anniversary

Posted by James Burke on February 18, 2025

As we commemorate the eightieth anniversary of the Battle of Iwo Jima, we ought also to highlight the men who served throughout Texas’s involvement. All those on Texas, in the fleet, and on the ground; from the first shell of bombardment to the raising of the flag on Mt. Suribachi contributed to the American victory. Three Texas crew members witnessed the battle from different angles. Alfredo Paloscio was a Fireman 1st class (F1c) and would have worked in the ship’s foreword electrical distribution compartment. Emory Lewis was a Quarter Master 3rd class (QM3c) stationed in either the pilot house or conning tower. Robert Zwoboda was a Fire Controlman 1st class (FC1c) and stationed on one of the superstructure fire control platforms, either in the foretop, aft fire control, or atop the main mast. Since Texas was the flagship of the bombardment phase of the battle, the actions of these three sailors carry even more significance, as the work they did directed not just Texas, but the American fleet behind her.

Items related to the Battle of Iwo Jima are spread across five different collections, three of which are named for their initial owners. Both Zwoboda’s and Paloscio’s families donated their uniforms to the Battleship Texas Foundation’s museum collection. Each has the golden “ruptured duck” patch marking an honorable discharge earned some time after Iwo Jima. While Paloscio’s uniform remains without a rate, Zwoboda’s has the FC1c patch sewn on the right sleeve. In addition, both sailors caps and slacks were also donated. Each article is carefully handled and placed within archival boxes to ensure their longevity. Acid-free tissue paper is added to maintain the shape and structure of the caps, as well as to keep the items stationary. The paper keeps the fabrics from rubbing on itself and potentially degrading the material. While the uniforms themselves are certainly interesting, the story of their owners is much more so.

Just after midnight on February 16, 1945, Texas met with her sister ship, the USS New York, and the rest of BatDiv5 and took up positions in the waters of Iwo Jima. She began bombardment with her main battery of 14” guns at 0803. Throughout the day, all three men would have been hard at work directing guns, maintaining the boilers, and steering the ship itself. Texas fired broadsides throughout the day, her engines and boilers cutting in and out as the ship steered around the future landing site. Paloscio maintained power to all systems, other sailors maintained the ship’s speed at a rather slow 2.5 knots while Lewis and others maneuvered her. As the flagship of the bombardment phase, each man’s work was even more essential, as New York and the rest of the ships in BatDiv5 kept pace with Texas. At 1705 bombardment from Texas ceased for the day. The speed of the ship was incrementally increased to 14 knots at 1915 for night maneuvers. While sailors like Zwoboda had some reprieve, those like Lewis and Paloscio continued working through the night.

It was a big shudder. I mean it was a lot of noise. You opened your mouth to sort of ease up the noise and all the concussion.Michael Scepanski, Seaman 1st class (S1c), on firing the 14” guns

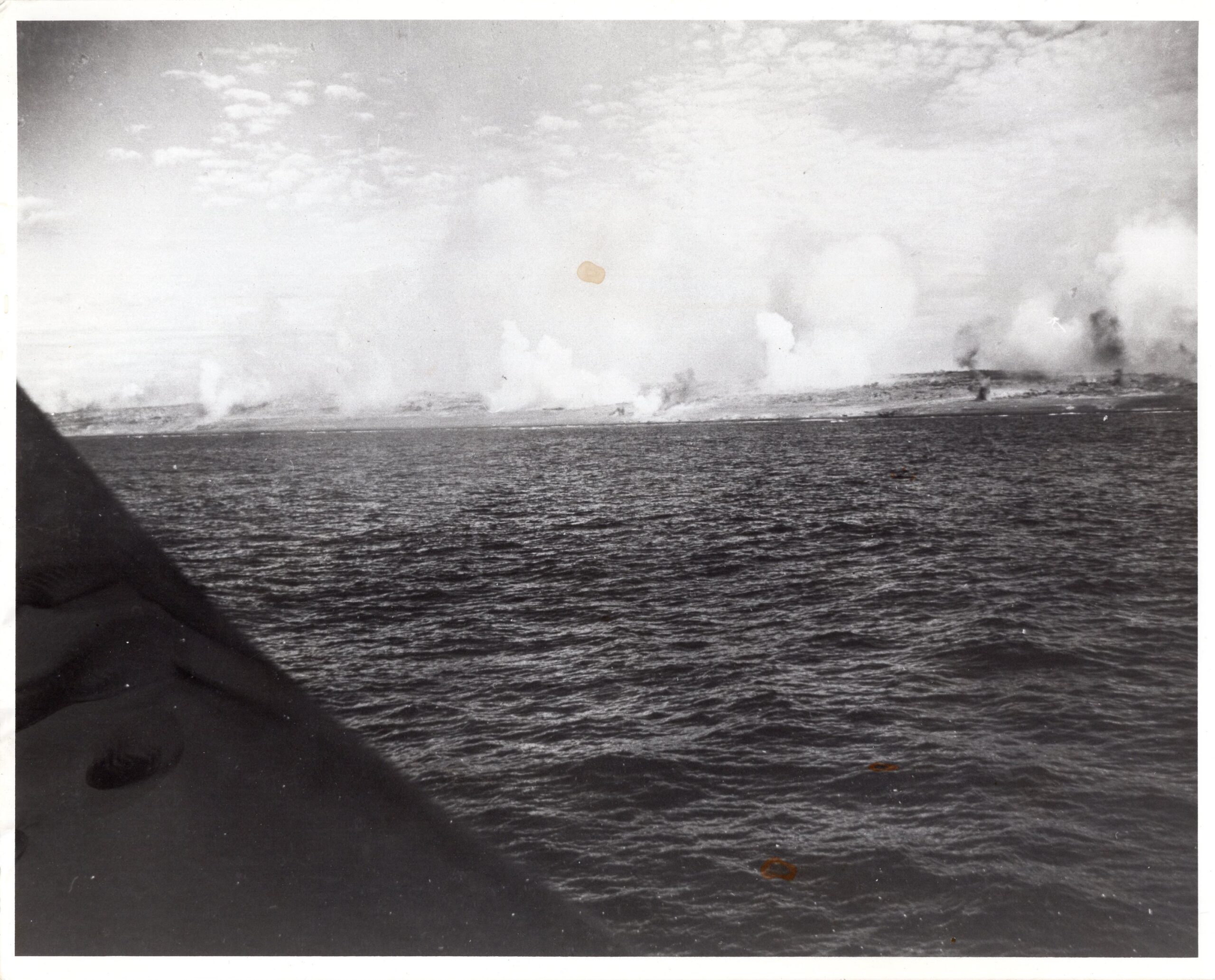

Texas began bombardment on February 17 at 0700. Her actions throughout the remainder of the bombardment phase mirrored her first day of action. As with the first day of the shelling, it is possible the uniforms in collection were worn by their respective owners during parts of the battle itself. Regardless, there remains other items from the battle that made their way to museum staff. On this day, men onboard the USS Arkansas (BB-33) captured photos of Texas right as she fired a broadside towards the beaches. By midday, those like Zwoboda focused fire on Japanese pill box positions on the island. Final bombardment ceased at 1840. Her night maneuvers and speed also mirrored that of the night prior. Action the following day was largely focused on coastal guns that hit USS Pensacola (CA-24) six times. Beginning at 0730, nearly two hundred 14” rounds were fired in revenge for damaging the cruiser. Her guns finally went silent at 1734. After which, she cruised around landing positions in preparation for the Marine landings to occur the next morning.

One time we [flew] around Suribachi. That was right at the period when we first spotted the rifle on the rails … And all of a sudden we went down a little lower, a little lower, and boy, I’ll tell you, all of a sudden that whole mountain started looking like a Christmas tree, and we got the hell out of there in a hurry.Thomas Koltuniak, Aviation Radio Technician 1st class (ART1c)

By the day of the invasion on February 19, Texas had fulfilled most of her role but remained in the waters around the island providing occasional fire support. Throughout the day her targets changed frequently to support the Marines on the ground. As her helmsmen and boiler workers kept her in movement, thousands of men stormed the beaches against what remained of the entrenched Japanese forces. Elsewhere aboard the destroyer escort USS Swearer (DE-186), a former Texas crew member Howard Flood worked to screen for potential air attacks by kamikazes. While Texas deck logs from the following days occasionally reported the spotting of anti-aircraft fire from her destroyer screen, and herself occasionally firing salvos of 14” and 5” rounds towards the island, the days after the initial bombardment were relatively tame for the dreadnought and her crew. Reports indicate a relatively uneventful guard for the old dreadnought. On February 23, 1945, the deck logs note Marines raising the US flag atop the island.

It was a moment of triumph when you saw the flag go up…We were sitting back with a panoramic view of the mountain and the troops going up the mountain and trying to get up to the top. It was a very heart-warming situation to see the flag come up.Enever Limerick, Seaman 1st class (S1c)

Texas remained in the waters surrounding the island for several weeks, and while occasionally sounding for air defense, never again fired her main battery. While Zwoboda certainly had some reprieve from rigorous duty, Paloscio, down in electrical, and Lewis at the helm, made sure the ship was in constant movement, often zigzagging the ship through fire support zones. While the guns of Texas remained silent, the fleet’s did not. Smaller craft, like those ships in the destroyer screen kept up the bombardment with 5” shells, often taking some themselves from remaining shore batteries. One of the most notable ships in Texas’ destroyer screen was USS Capps (DD-550), through which a photo of the later shore bombardment made its way into collection. Though the battle itself would not end for some time afterwards, Texas left the island’s shores on March 7, 1945.

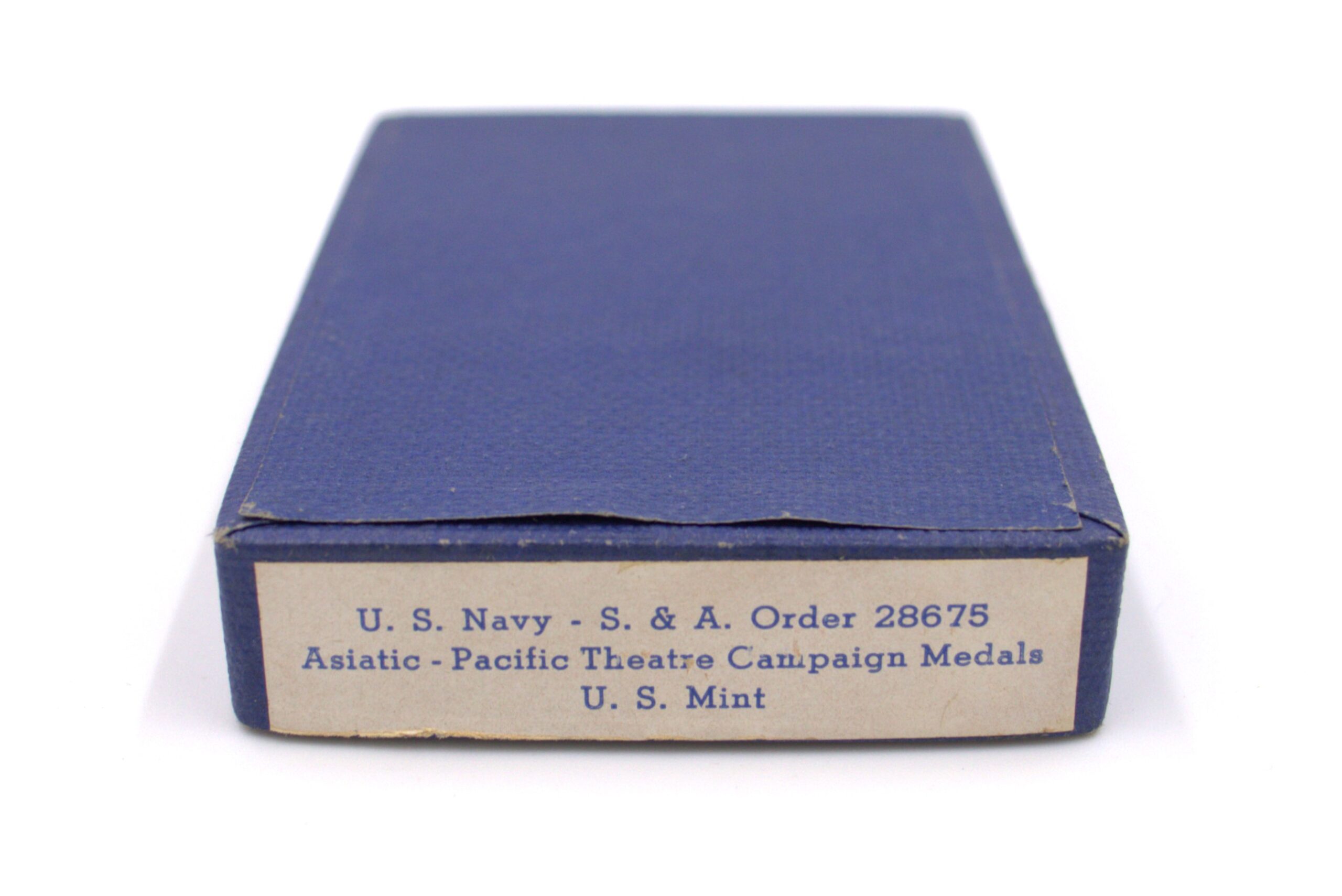

Iwo Jima was far from the first battle Texas took part in during WWII, but it was the first time she took the fight to the Japanese; her preceding service opposed Nazi Germany in Europe and North Africa. While Texas and her crew would continue to serve in the Pacific island-hopping campaign, and next provide fire support on the shores of Okinawa, their participation at Iwo Jima earned them recognition. Zwoboda, Lewis, and Paloscio, along with the other near two thousand men serving in the various roles aboard Texas, would have each earned the Asiatic Pacific Campaign Medal, one of the three campaign medals awarded by the US Navy. Emory Lewis earned the medal shown here. If you want to learn more about Battleship Texas Foundation’s collection of medals earned by her crew, and how the curatorial department preserve and store them, you can read about them here.

Generous donors give new and interesting artifacts to Battleship Texas Foundation regularly. The Battle of Iwo Jima represents an important phase in the history of Battleship Texas, and the Allied efforts in the Pacific. The items we have allow us to interpret the battle not just from the fleet perspective, but the sailors and marines themselves. The Battleship Texas Foundation is actively collecting historic items, photographs, and documents related to Battleship Texas (BB-35), Battleship New York (BB-34), or the other commissioned ships named USS Texas (SSN-775, CGN-39, and the first USS Texas commissioned in 1895). If you have an item that makes you say, “It belongs in a museum!” please email us at [email protected] with photos and any relevant information. Our staff is working diligently to collect, accession, and archive historical items of the Last Dreadnought.

James Burke is a History PhD candidate at the University of Houston and has worked as curatorial staff with Battleship Texas since 2020.