History

Battleship Texas led a distinguished 34-year career in the United States Navy. In that time, she fought in both World Wars, earned a number of “firsts”, and was home to tens of thousands of sailors and marines from all walks of life. Texas served with the Grand Fleet during the First World War and earned five battle stars during the Second World War. She fought in North Africa, Normandy, Southern France, Iwo Jima, and Okinawa, and through it all only lost one crew member to enemy fire. In 1948, Battleship Texas was donated to the State of Texas to serve as a museum and memorial. In the words of her last captain, Charles Baker, “Her wars are over, she has won the right to rest peacefully in Texas waters.”

The Early Years

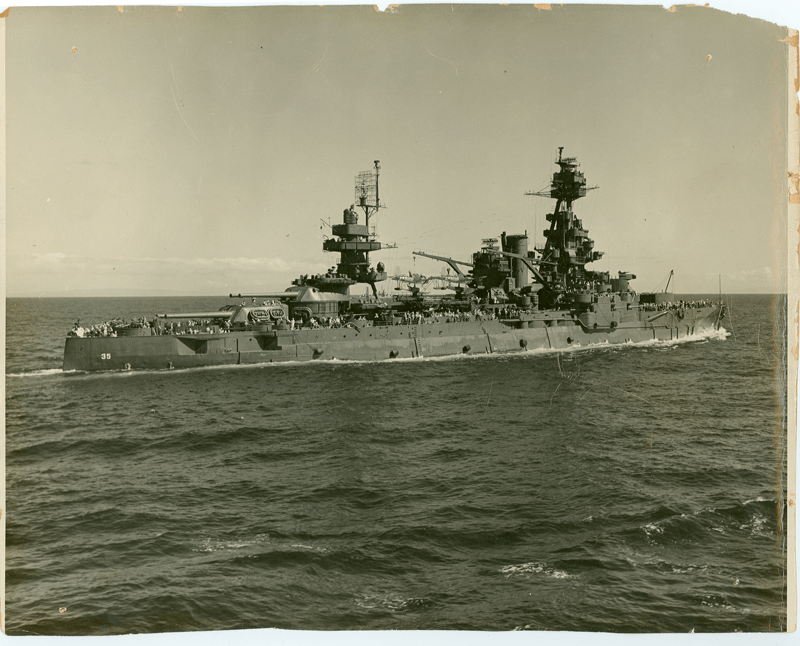

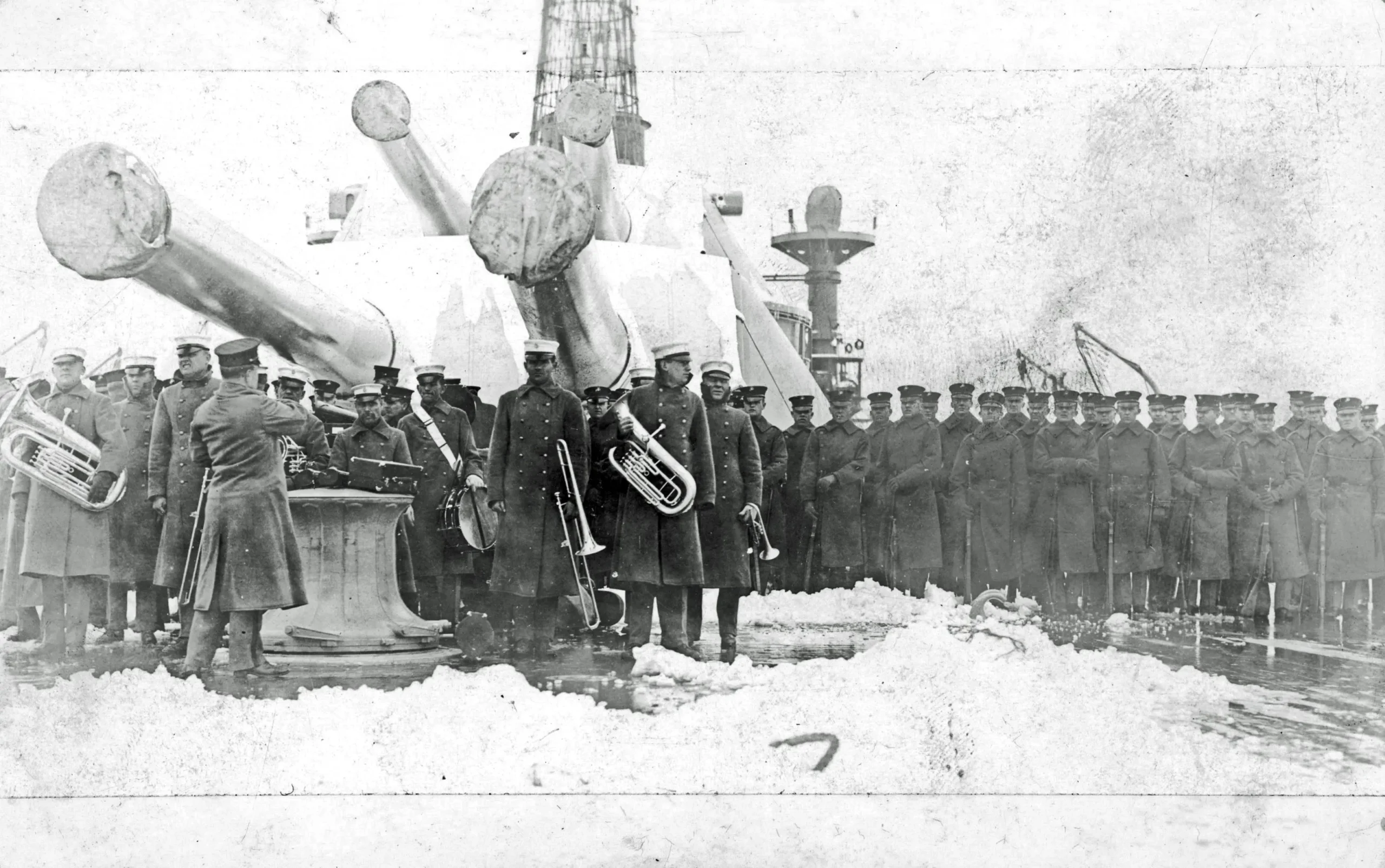

Battleship Texas was commissioned on March 12th, 1914 at Norfolk Navy Yard. The day was cold and snowy and, much to everyone’s relief, Captain Albert Grant kept his remarks to a brisk five minutes. At commissioning, Battleship Texas was considered the most powerful weapon in the world. She carried ten 14”/45 caliber guns, the largest guns on any ship at the time and the first American battleship armed with them. Her guns could fire a 1,400 pound shell loaded with over 100 pounds of high explosives up to 12 miles.

When Battleship Texas was commissioned, the United States was entangled in the Mexican Revolution. Skirmishes along the US-Mexico border were regular front page news around the country and the United States had deployed battleships off the coast of Mexican ports, intent to intervene if American citizens there or American interests were threatened. On April 9th, 1914, with Texas still awaiting a proper “shakedown” cruise, there was a diplomatic incident in Tampico, Mexico, in which a small party of American sailors were detained and released shortly after. The reaction to the “Tampico Affair” ultimately spiraled out of control and led to the Invasion of Veracruz on April 21st, 1914.

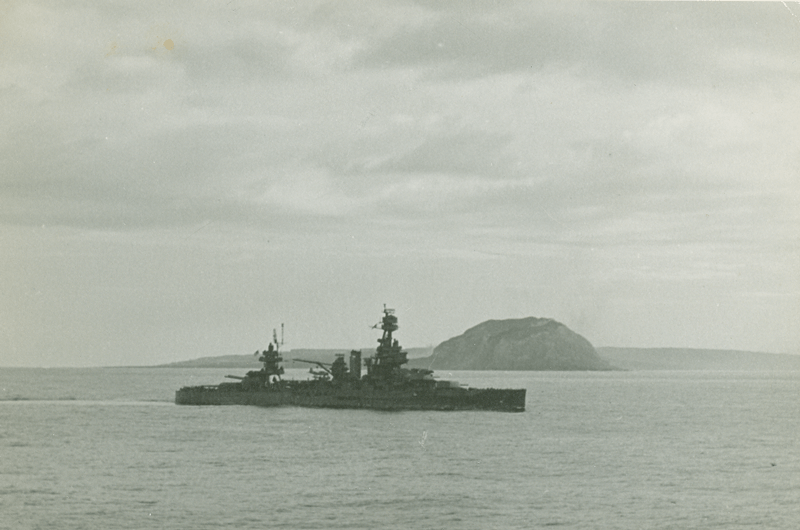

In May of 1914, Battleship Texas was deployed to Veracruz to support the occupation there – her first visit to foreign waters and her first “action”, albeit the fighting was already over. In November, Battleship Texas paid a short visit to Galveston, Texas, her first visit to Texas and her last visit until she returned as a museum in 1948. In Galveston, she was presented with the silver service from the 1895 Battleship Texas at Old Ball High School, then with her own silver service during an onboard ceremony.

In 1917, Battleship Texas shipped out for the First World War under the command of Captain Victor Blue, Texas’ longest serving commanding officer. Unfortunately, she ran aground on Block Island shortly after leaving Long Island Sound. As the crew lightened her load over several days and worked to get her free, sailors on passing ships would shout “Come On Texas!” which stuck as the ship’s motto through the rest of her career. Texas later made it across the Atlantic to join the Grand Fleet in January 1918.

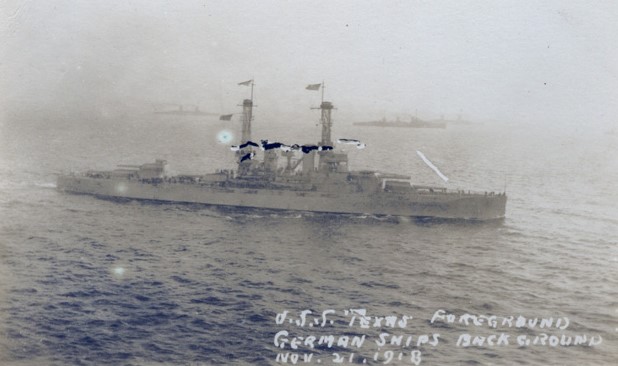

Texas and the Grand Fleet patrolled the North Sea until the end of the war, but there were no major battles in that time. The German High Seas Fleet surrendered to Texas and the Grand Fleet on November 21st, 1918. The surrender was the single largest naval victory in history, all without firing a shot.

Modernization

In 1919, Battleship Texas was used in an early naval aviation experiment. On March 10th a Sopwith Camel biplane was successfully flown off a ramp constructed on top of Turret #2, making her the first American Battleship to launch an aircraft. The pilot was Commander Edward McDonnell, who previously earned the Medal of Honor at the Invasion of Veracruz in 1914.

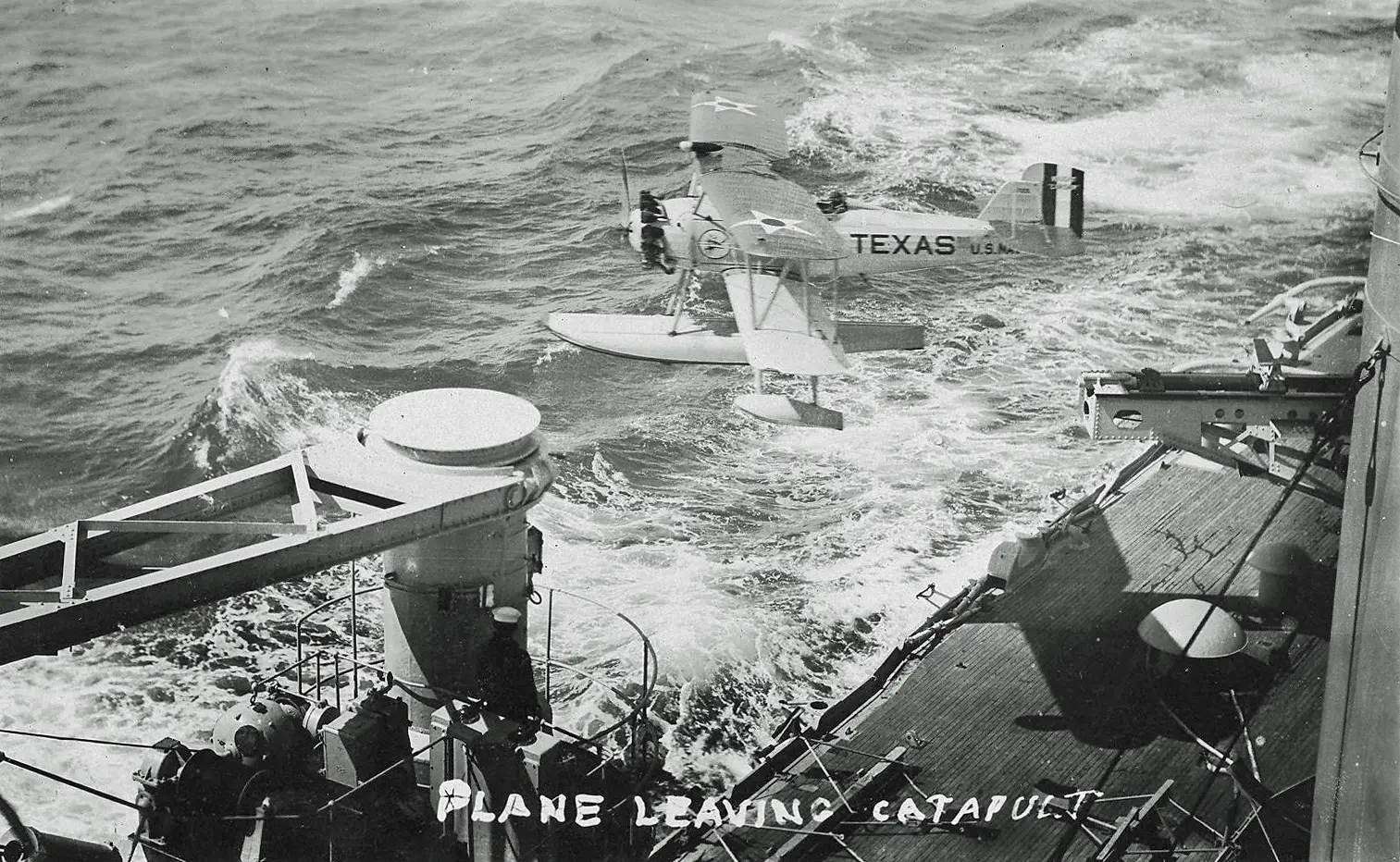

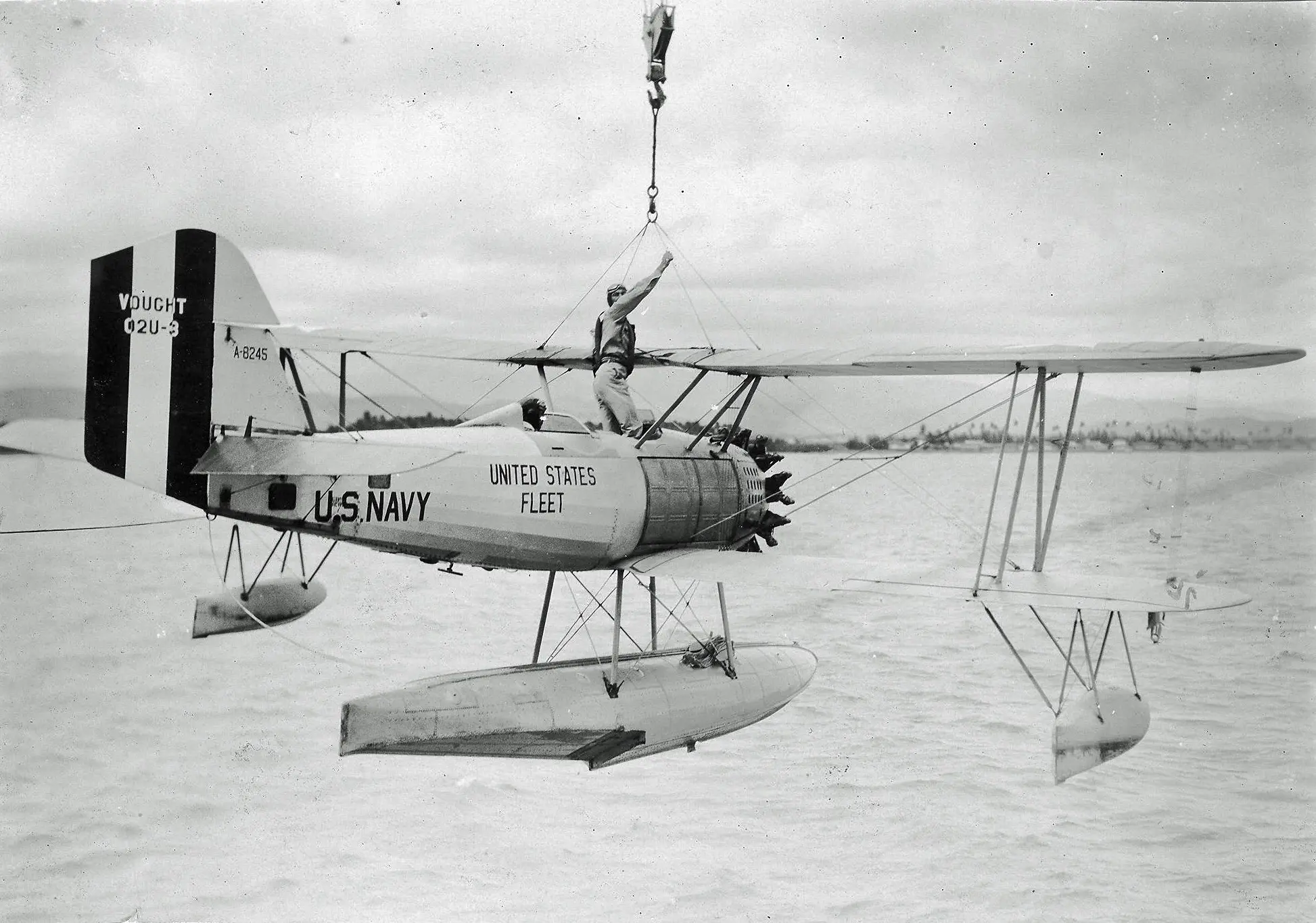

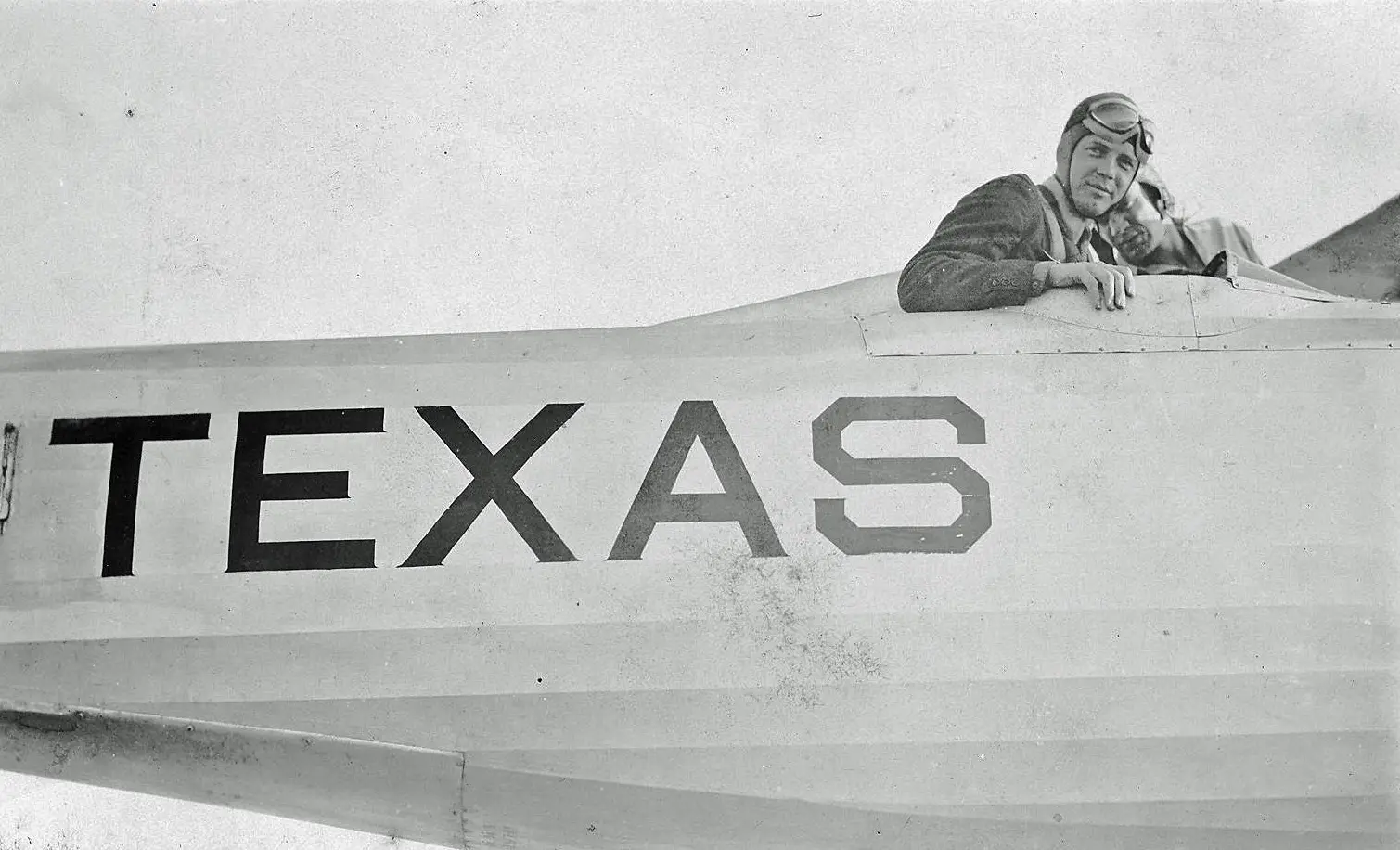

In 1925 – 1927, Battleship Texas was heavily modernized. The Washington Naval Treaty in 1922 had ended the construction of new battleships worldwide, so older battleships like Texas were upgraded rather than being scrapped and replaced. Battleship Texas had her cage masts replaced with sturdier tripod masts, her fourteen coal fired boilers replaced with six fuel oil fired boilers, torpedo blisters were added to her hull for increased torpedo defense, and a purpose-built aircraft catapult was installed on Turret #3.

The Interwar Years were peaceful for Battleship Texas, but still eventful. After her modernization, Battleship Texas was the Flagship of the US Fleet from 1927-1931. She carried President Calvin Coolidge to the Pan-American Conference in Havana, Cuba in 1928. Battleship Texas played host to many distinguished visitors, from Olympians like Helen Wills Moody to foreign leaders such as President Gerardo Machado of Cuba, to the famous aviator Charles Lindbergh. Texas continued to be upgraded over the 1930s as well. In 1935, eight Browning .50 caliber machine guns were installed for air defense. In 1939, Texas and her sister, Battleship New York, received experimental air search radar.

The Second World War

When the Second World War broke out in Europe in 1939, Battleship Texas was assigned to neutrality patrol, escorting merchant ships across the Atlantic. When Japan attacked Pearl Harbor on December 7th, 1941, Battleship Texas was in Casco Bay, Maine, preparing for her next patrol. With the United States now officially at war with the Axis powers, Texas continued her patrols until late 1942, when she took part in Operation Torch – the Invasion of French North Africa.

Operation Torch, the Invasion of French North Africa on November 8th, 1942, was the first major combat seen by Battleship Texas. Texas supported the attack on Port Lyautey, Morocco, where the Army sought to take over a strategic air field. After three days of fighting, the operation was a success and French North Africa was brought back into the war on the side of the Allies.

A young Walter Cronkite was on board for the battle, working as a war correspondent for United Press. Hoping to beat a rival reporter back to the US so he could publish his stories first, on the return trip to the United States, Cronkite flew off the ship early with a pilot named Frederick Dally. Cronkite went straight to work and beat the other reporter, publishing the first uncensored stories from North Africa.

The Liberation of France

In the spring of 1944, Texas and her crew began preparing for an unknown major operation. General Eisenhower came aboard in May 1944 to meet with Captain Charles Baker about the operation. While he was aboard, he delivered a short speech to the crew on the fantail and by the end of the month, Texas’ crew finally found out what they had been training for – the Invasion of Normandy.

On June 6th, 1944, “D-Day”, Texas was assigned to support the landings of the Army Rangers at Pointe du Hoc and the landings at Omaha Beach. Texas opened fire on her assigned targets at Pointe du Hoc at 0550, firing 255 fourteen inch shells over the next 34 minutes. Texas then moved to Omaha Beach to support the main landings. On June 7th, Texas learned that the Rangers on Pointe du Hoc were in serious trouble. Texas sent ashore two landing craft full of ammo, food, water, and medical supplies. The Rangers sent back 35 wounded Rangers and 27 prisoners of war. Only one of the Rangers sent back to Battleship Texas died of his wounds, Staff Sergeant Leon Otto.

On June 25th, Texas was sent to support the Battle of Cherbourg. After the landings at Normandy, the forces at Utah Beach were sent north, up the Cotentin Peninsula to secure the city of Cherbourg, a strategically important deep water port. Texas was sent with other battleships and several destroyers to engage the German artillery stationed around the city, to keep their fire off the US VII Corps as they finally broke out and into the city.

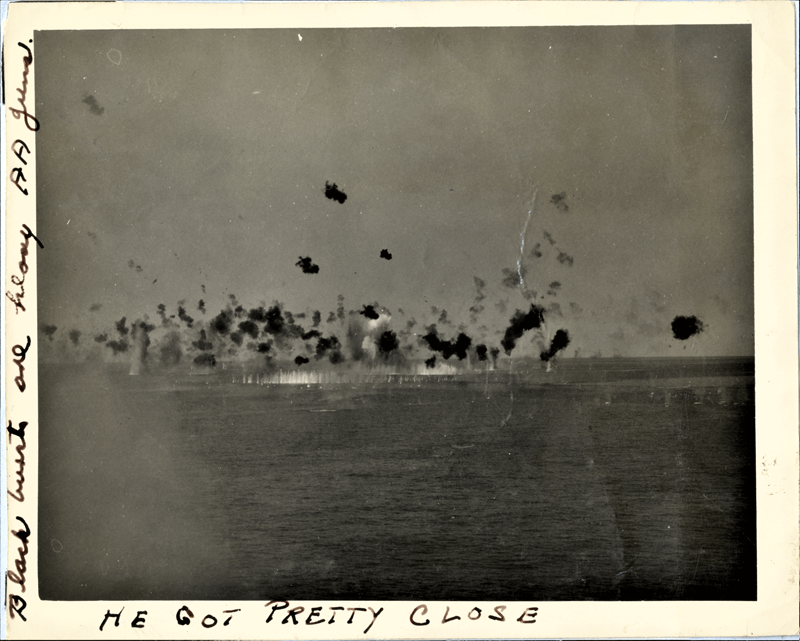

Texas was straddled by dozens of near misses from artillery and was eventually hit at 1316. A 240 mm German shell struck the top of the conning tower, wrecking much of the navigation bridge above. Eleven people were wounded and only one of them died of his wounds, the helmsman QM3c Christen Christensen. Chris was the only member of the crew to be killed in action through Texas’ entire career.

One other shell hit Texas at the Battle of Cherbourg, a 240 mm dud. The shell landed in a warrant officer’s stateroom and failed to explode, possibly due to the way it appeared to have skipped off the water and tumbled into the ship rather than hitting head on.

When Texas returned to England after the battle, Ensign Stephen Sturdevant was brought aboard to help defuse the shell. Under his supervision, the shell was removed from the ship and defused without incident and Sturdevant was later awarded the Bronze Star in part for defusing that shell. The shell returned to the ship shortly after and remained as a trophy.

After repairs were completed, Battleship Texas went to the Mediterranean for Operation Dragoon, the Invasion of Southern France. Southern France proved to be a far easier operation than the Invasion of Normandy, largely due to the overall success at Normandy.

Battleship Texas arrived off the coast of Sainte-Maxime, France in the early morning of August 15th, assigned to destroy a battery of five 220 mm guns. Visibility was extremely poor that day and Battleship Texas was never able to get a clear view of the German guns. Despite this, Texas was able to hit her targets with spotting from the destroyers Fitch, Emmons, and Rodman. The next day, Texas closed to within 3,000 yards of shore to wait for calls for fire support, but none came. During the night, Texas was ordered to Palermo, Sicily and on August 17th the German Army was in full retreat from Southern France.

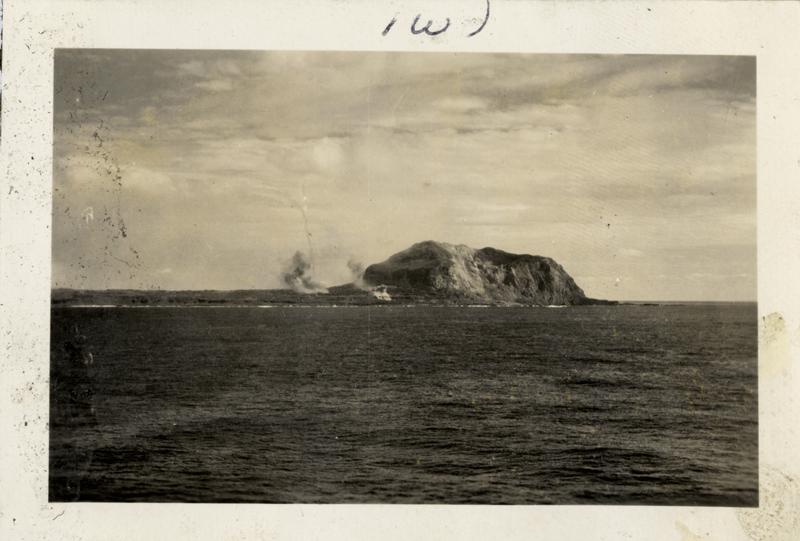

Iwo Jima

After the Invasion of Southern France, Battleship Texas returned to the US for another round of upgrades and modifications before she went to the Pacific. Texas received new radar and fire control systems and several hundred of her crew was reassigned and replaced. She made it to the Pacific just before the end of the year and was sent to the Battle of Iwo Jima in February. At Iwo Jima, Texas and her crew saw some of their most intense fighting to date. For many crew members, this was the first time they had seen up close what was on the other end of their guns. The anti-aircraft gun crews faced their first real challenge as well – Japanese air raids had proven a persistent threat throughout the war in the Pacific. Here’s one crew member’s memory of the day the Marines landed on Iwo Jima, February 19th.

“The day of the invasion, we appeared on the real landing beach and lowered our main battery guns right onto the shore and just blasted the entire area, trying to clear away where the landing took place. The most amazing thing without a doubt, after we lowered our main battery and 5-inch 51s and fired right straight into shore, we were no more than three-quarters to a half a mile away from shore. And to see the devastation that the 14-inch guns would cause when they hit the shoreline, and the swaths that they would cut through the coral and the sand beach, I just didn’t think anything could live and stand that kind of punishment. However, when we stopped firing and the landing craft passed our ship and went into the beach, we actually saw tanks, these old Japanese, looked like to me World War I vintage tanks, come lumbering down the hillside there to meet the landing craft and the Marines that were coming ashore. I couldn’t believe that that could occur. It just, still in my mind, shocked me.”-Enever Limerick, USN, Battleship Texas Crew Member

Texas’ crew also witnessed one of the most iconic moments of the war in the Pacific, the raising of the flag atop Mount Suribachi. Much of the crew gathered on main deck to watch the flag-raising, a welcome respite for them.

Okinawa

By this time, Battleship Texas was equipped with a staggering number of anti-aircraft guns. With ten 3″/50 caliber guns, ten quad 40 mm Bofors, and forty-four 20 mm Oerlikons, even an old battleship like Texas was an intimidating target for an enemy pilot. Over those 50 days at Okinawa, Texas fired nearly 6,000 rounds of anti-aircraft ammunition and made it through without a scratch on her. Texas had set a record for days at battle stations and won her last battle.

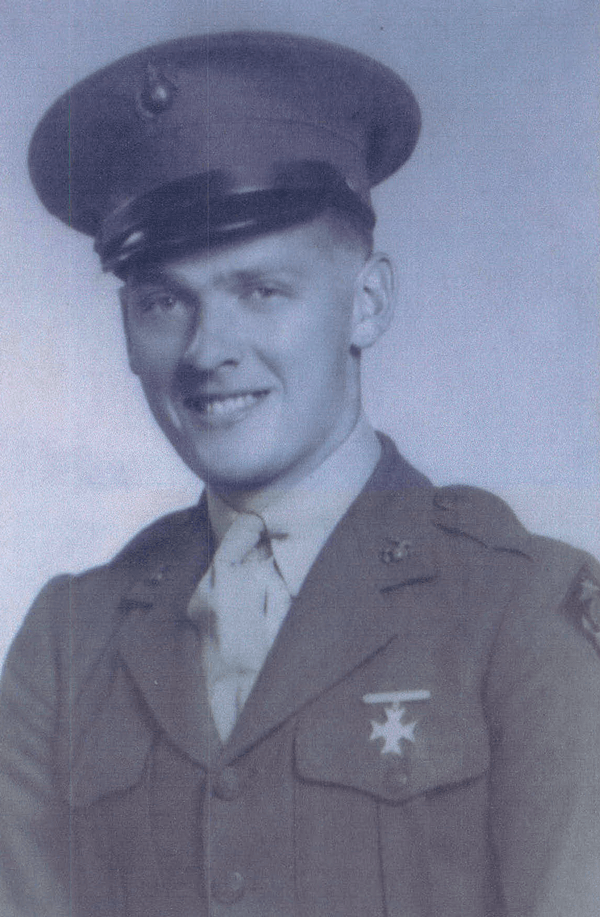

“We kind of felt irritated towards our captain, Charles A. Baker, who kept us in [battle stations] for all that time. As it turns out, he was doing the very thing he was supposed to do because some of the other ships, for instance the battleship Tennessee was a few hundred yards to our port, I could see it real good. One morning about dawn we got word that they were coming. So [on the Tennessee about] two-thirds of the crew had gone below. So when they sounded general quarters you could hear that “Bong, bong,” I could hear it from their ship all the way over to us. You could see them running just like monkeys trying to get to their battle stations. In the meantime one of those Japanese kamikazes hit them on a quad-forty gun mount just like the one that I was on.”–Ralph Fletcher, USMC, Battleship Texas Crew Member

Okinawa was Texas’ final major battle and by far the hardest. Having seen the damage inflicted on other ships by Japanese air raids at Iwo Jima, Captain Baker made the decision to order the entire crew to remain at their battle stations for the duration of the battle, over 50 consecutive days. Men would sleep when and where they could, not returning to their bunks. Food was delivered to the men at their battle stations and was mostly K Rations, an early predecessor to modern MREs.

Magic Carpet

When the war ended, Battleship Texas was in Leyte Gulf awaiting an eventual invasion of Japan. Texas’ crew knew nothing of atomic bombs, only that the war was finally over. Captain Baker gave a brief speech to inform the crew and thank them for their efforts, then turned the ship over to them for celebration. Crew members recall a massive party breaking out on the ship, flares being fired off like fireworks, and a Conga Line that a few sailors had convinced Captain Baker to lead.

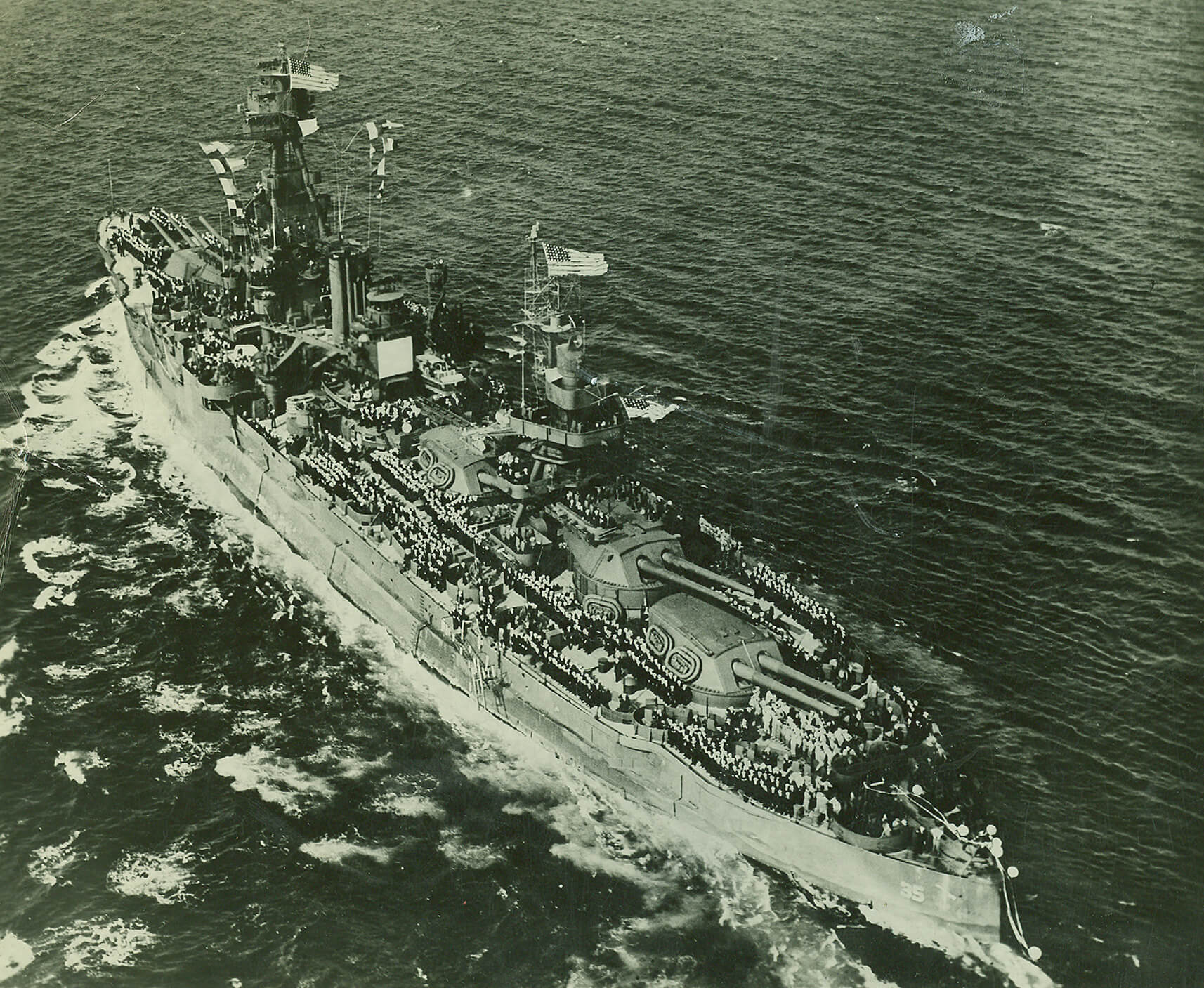

It was time to go home, but there were over 12 million Americans serving in the Army, Navy, Marine Corps, and Coast Guard at the end of WWII. The War Shipping Administration devised a plan to repatriate these millions of Americans, Operation Magic Carpet. Battleship Texas completed four “Magic Carpet Rides” between October and December 1945, carrying home as many soldiers, sailors, and marines as would fit aboard. Here is one veteran’s recollections of Operation Magic Carpet

“We were on the Magic Carpet detail. The service men on the islands that were eligible for discharge under the point system, had to be brought back to the States. The Texas was one of them. Every time we made a trip back to the States, we would lose some of our own personnel. Because, I was like USN, I was in on a six-year enlistment. But, others were USNR, Reserves, and could be discharged on a forty-four point system. The result was we were losing members of my own crew. So, on one occasion, I had to use people that were being transported, if they had an engineering rating, I would have to put them on watch in order to get the ship moving. I recall on one occasion where I had to line up every piece of equipment in both port and starboard engine rooms myself and I would have to instruct them to watch the pressure gauges.”-Walter Zessin, USN, Battleship Texas Crew Member

Decommissioning

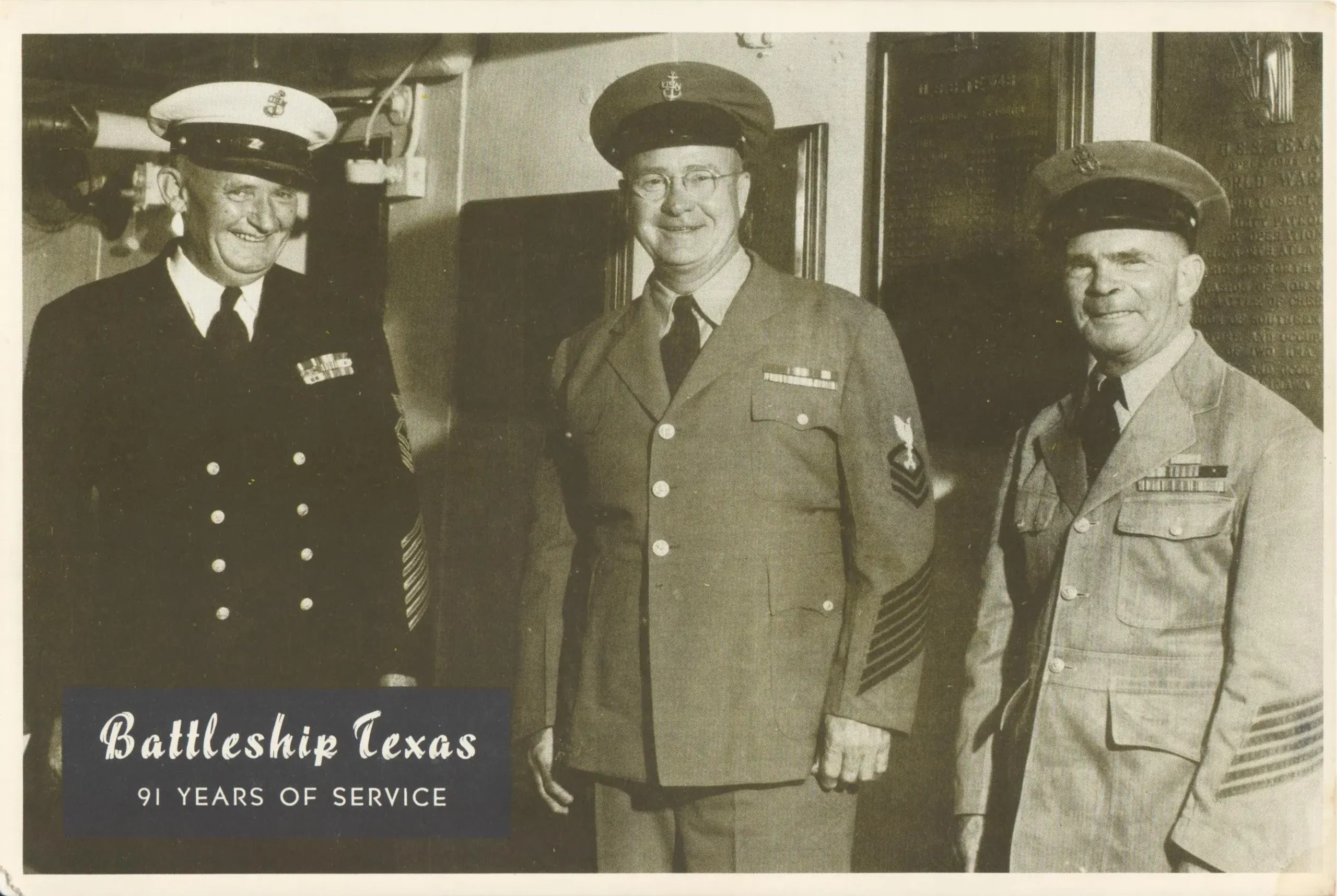

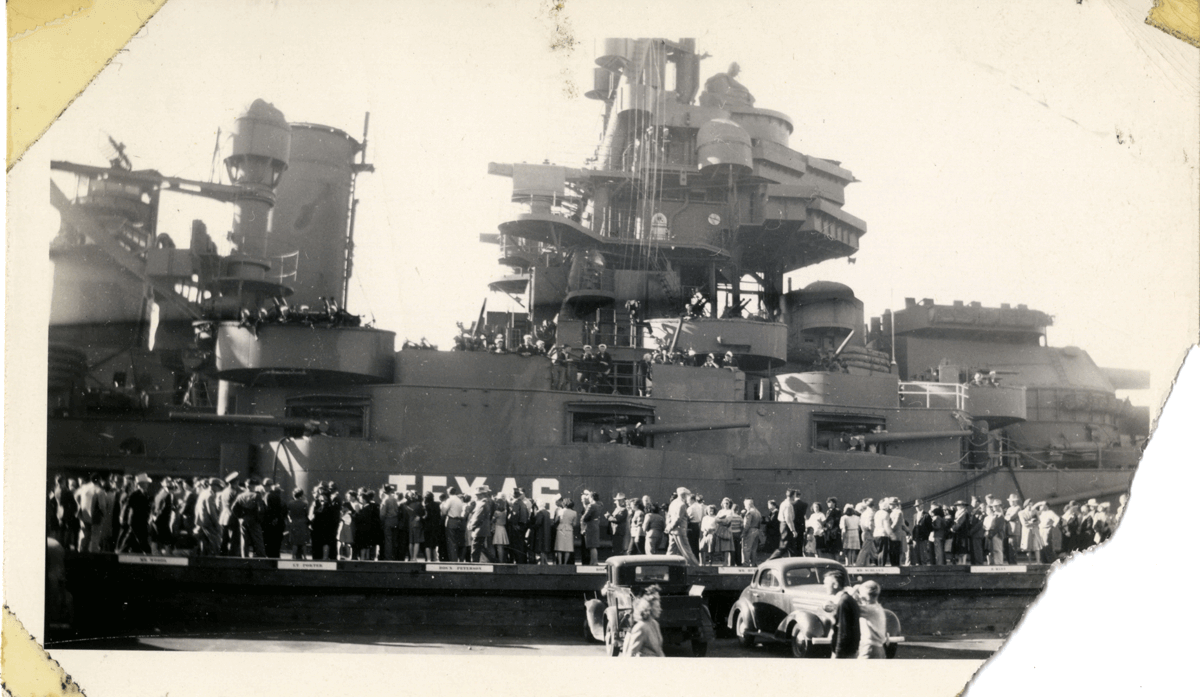

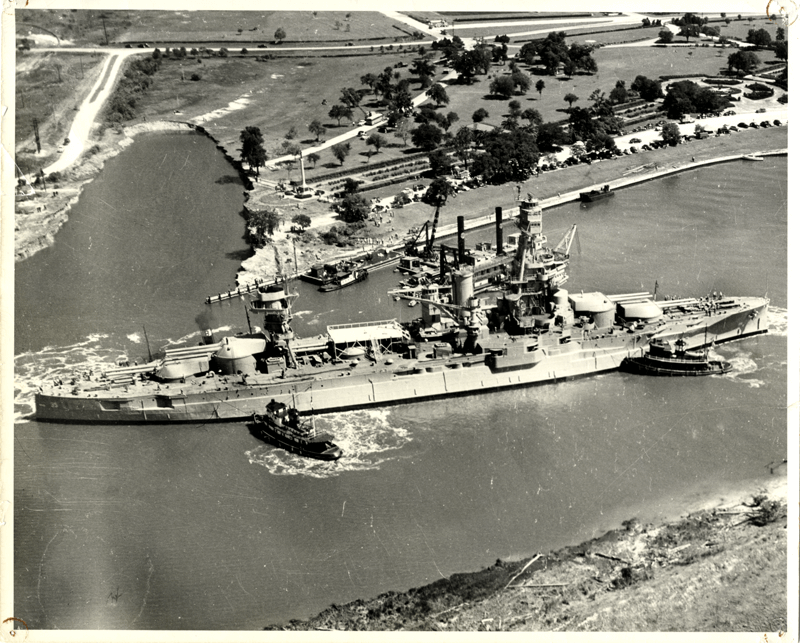

In 1946 Battleship Texas was put into the reserve fleet. By this time her fate was already known, she was to be donated to the State of Texas to serve as a memorial and museum. After two years of planning, preparation, and legislating, on April 21st, 1948 Battleship Texas arrived at the San Jacinto Battleground near Houston, Texas. Captain Baker was made captain of the ship again for that day, so that he would be the last captain of Battleship Texas.

Most of the final crew – only about 130 men by this time – was reassigned to USS Wisconsin after the ship’s decommissioning on April 21st. Chief John Jack McKeown, who had been serving on Texas since 1937, was discharged from the Navy that day so that he could become the ship’s caretaker. Chief McKeown lived aboard the ship and continued as her caretaker until shortly before his passing in 1970.