Kapok: America’s Lifesaver

Posted by Hunter Miertschin on August 7, 2025

The United States Navy’s hunt for a better life jacket

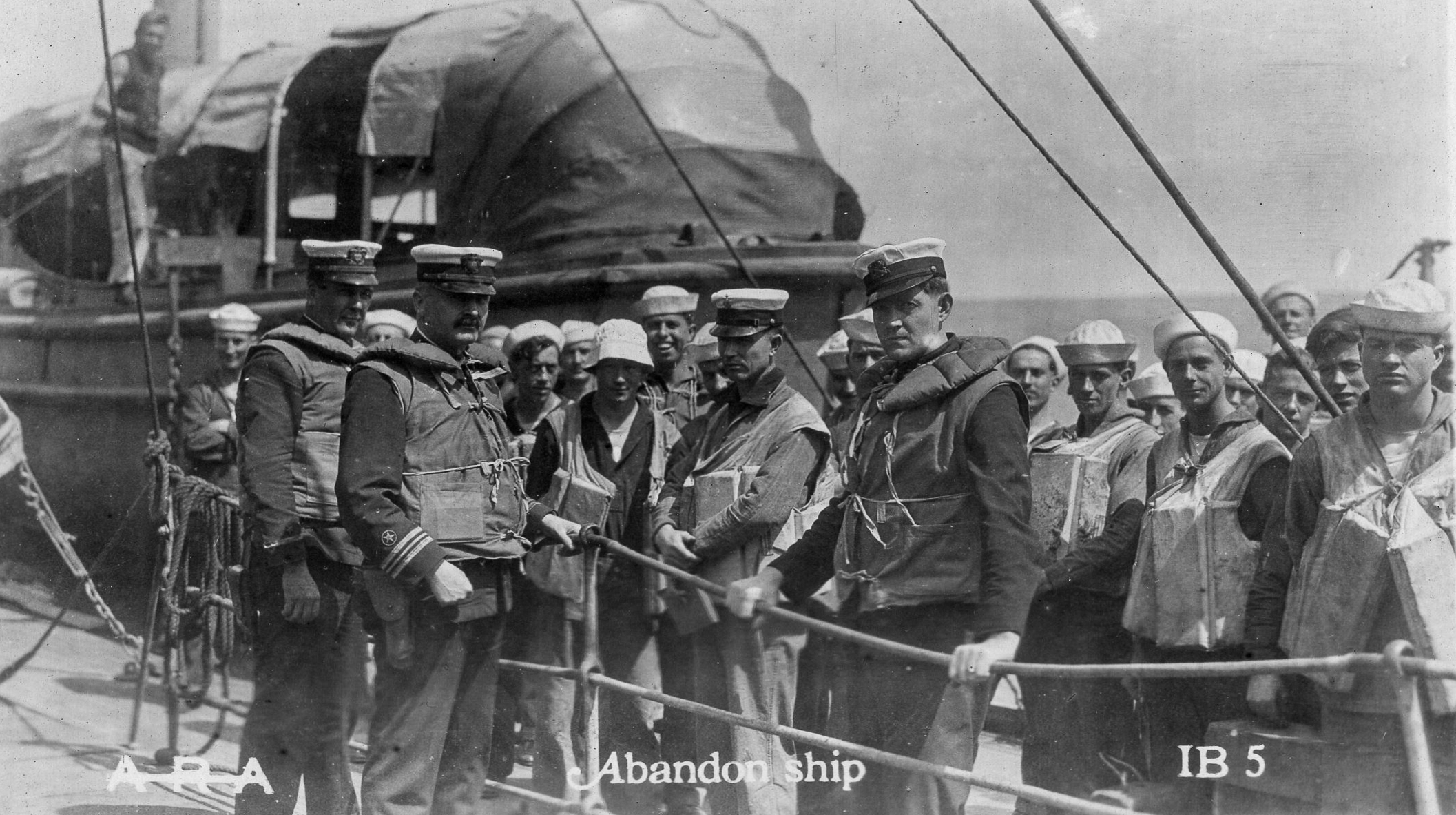

Throughout the late nineteenth century and the beginning of the twentieth century, various nations used cork life jackets aboard small fishing boats and large ocean liners like the RMS Titanic. The cork, sourced from the bark of the Quercus suber tree, was placed into a canvas vest or life jacket, giving these jackets a distinctive, rigid, and blocky shape. However, despite the high buoyancy properties of the cork, the slabs were bulky and heavy, with many wearers finding them uncomfortable. Additionally, those forced to abandon ship and jump into the ocean could sustain serious injuries to the neck, arms, and collarbones. The United States Navy considered these shortcomings when looking for a material to fill their new life jacket.

Pre-World War I

As early as 1915, the United States Navy began using a vegetable fiber filler known as kapok to produce its life preservers and jackets. The fiber is sourced from the pods of a kapok tree, or Ceiba Pentandra, native to tropical regions with distinct dry and rainy seasons, including Java, India, Burma, and the Philippines. Inside the tree’s pods is a lightweight, silky fiber with a water-resistant outer waxy coating, which helps disperse the seeds when the pod blooms. The material was extremely buoyant, pliable, and could resist water for lengthy periods when wet, making it a near-perfect fit for the Navy’s needs.

World War I

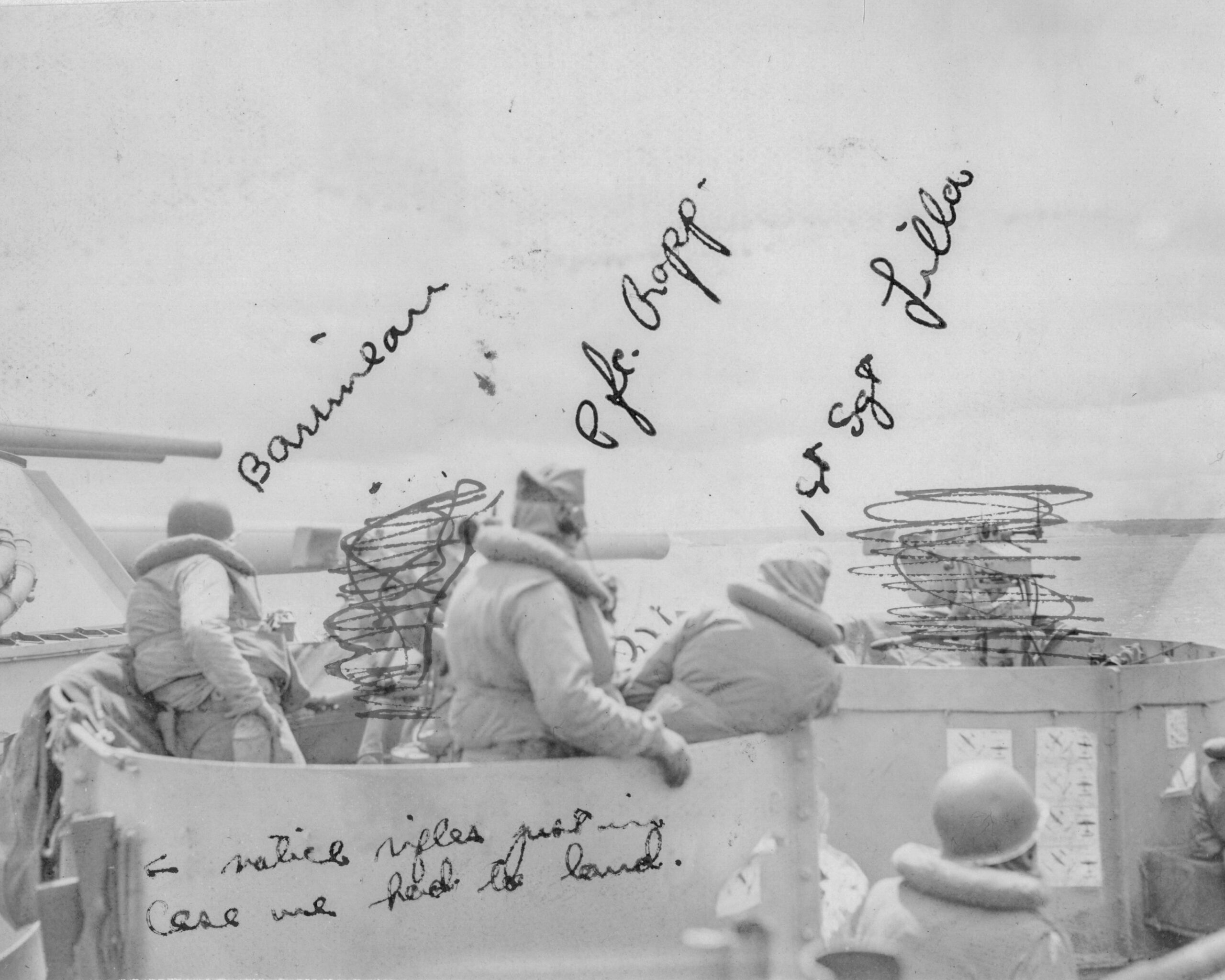

When the United States entered World War I, a waistcoat-like garment filled with kapok fiber would debut within the United States Navy. Secured around the wearer with cotton ties, a large collar behind the wearer’s head, and two patch pockets on each side, the Navy’s kapok life jacket was born. Those equipped with the new life jacket would soon realize its importance as unrestricted submarine warfare now threatened to sink every ship traveling between the United States and Europe.

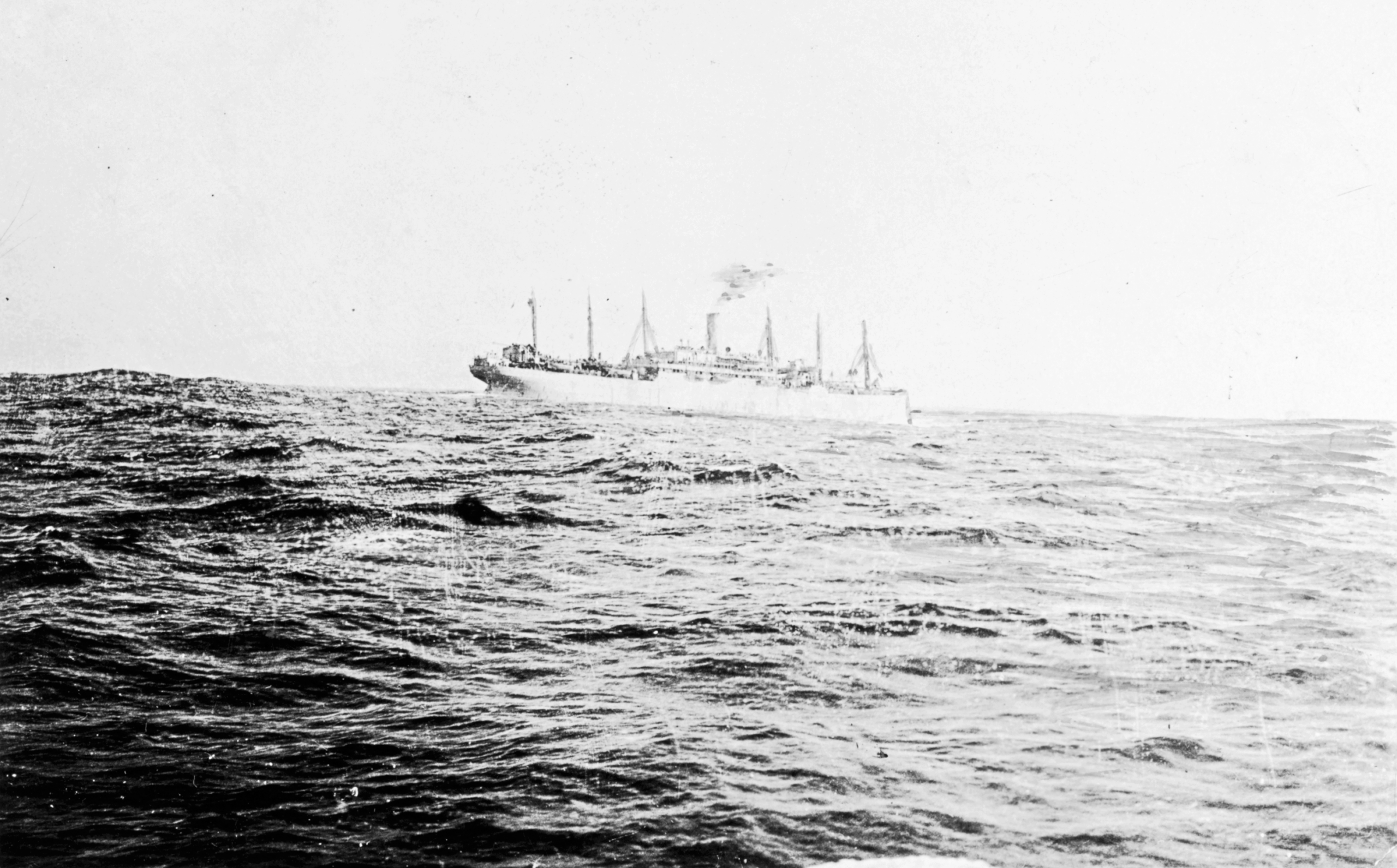

Sinking of the USS PRESIDENT LINCOLN 1918

On May 31, 1918, the ocean liner, now a troop transport, USS President Lincoln, was underway to New York from Brest, France, when a German U-boat attacked it. Sinking rapidly from the three enemy submarine torpedoes, the crew and passengers donned their life jackets, lowered the lifeboats, and prepared to abandon ship. Forced to jump into the North Atlantic Ocean, the men relied on the life jackets to keep them afloat as they swam away from the sinking ship and towards a lifeboat or raft. Miraculously, of the seven hundred crew and passengers, only twenty-six were lost, with the survivors rescued by the destroyers USS WARRINGTON (DD-30) and USS SMITH (DD-17) after eighteen hours of being stranded at sea.

I was relieved at eight and went directly to the mess hall for breakfast. After breakfast I went to my quarters to stow my gear. I heard and felt an explosion. I first thought maybe one of the gun crews was having target practice. Then there were two more explosions and the battle alarm was sounded. I rushed to my bunk, picked up a life vest, and went to my battle station. It was then and only then that I realized we were sinking. You could look down the cargo batch and see the water rising. Whitey Cramer, the senior NCO, passed the word along after it came down from the bridge, “All hands, abandon ship.”Samuel Hart, USS President Lincoln crew member

World War II

In 1940, the United States passed the Two-Ocean Navy Act, expanding the nation’s Naval force by seventy percent, increasing demand for the strategic and critical material for life jacket production for the thousands of service members who would serve aboard the growing fleet. The continued expansion of the Japanese Empire throughout the Pacific in late 1941 meant the United States had lost access to the Dutch East Indies, the colony responsible for providing ninety-five percent of the country’s imported kapok. This loss of a major supplier caused the United States to continue collecting and stockpiling as much of the resource as possible. By the end of 1941, a familiar life jacket, with little change from its predecessor, was worn by sailors from a nation at war it did not want.

The United States Government authorized a total procurement of 16,980,000 pounds of fiber from foreign and domestic stockpiles, limiting its use during wartime and restricting higher-quality grades of kapok for life preserver use by 1944. Meanwhile, the Department of the Navy obtained an additional 1,752,189 pounds of Java kapok to be placed in a special reserve and used in its manufacturing facilities. By 1945, the Navy required nearly seven million pounds of the fiber for use in its life jackets, and all existing stocks were expected to become exhausted at the end of the year.

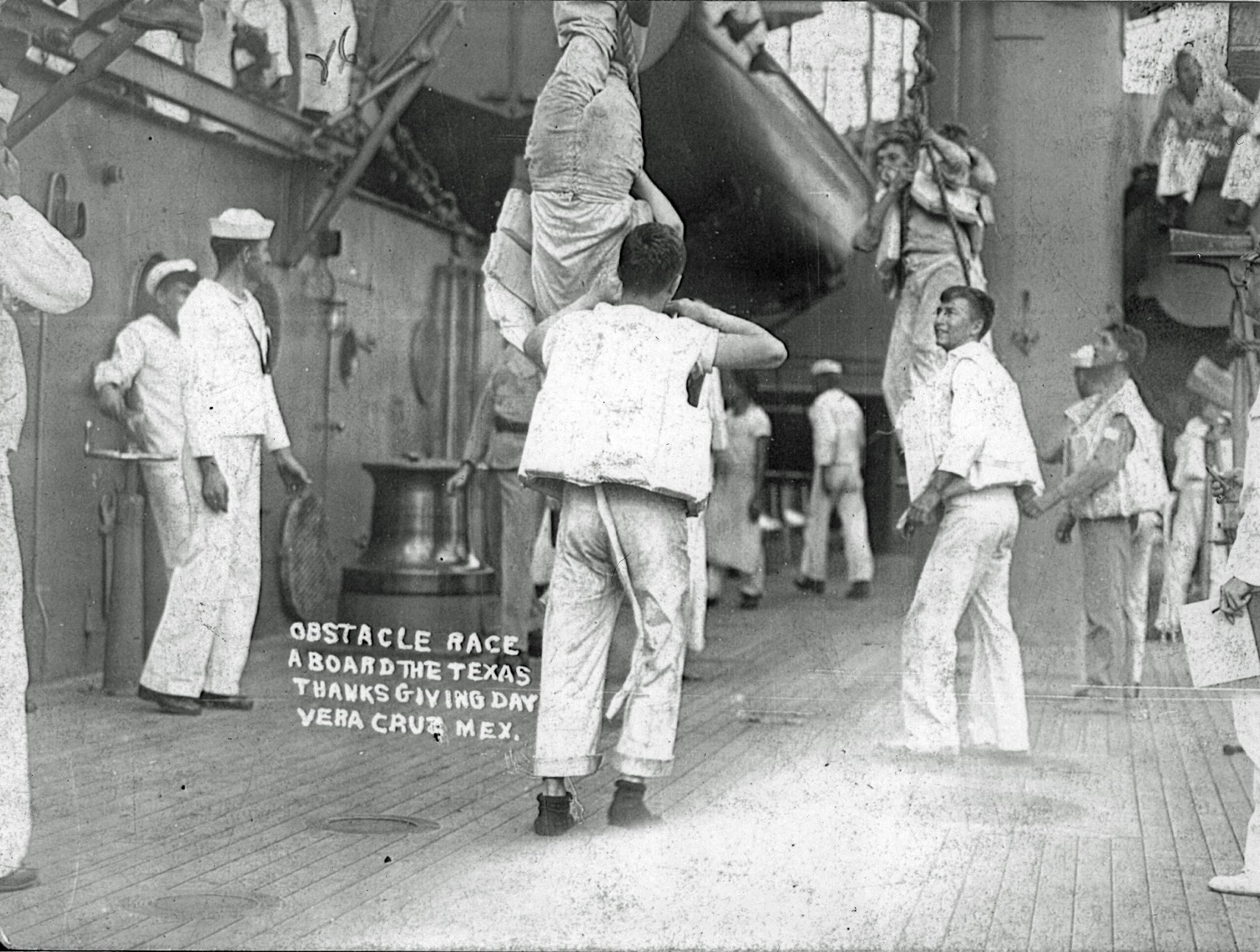

While the life jackets were excellent floating devices, they also protected their users against flying fragments. Sailors and Marines with battle stations located on and above the main deck aboard the USS TEXAS (BB-35) were supposed to wear their steel helmets and the KAPOK life jackets for the excellent splinter protection they offered.

The Allied invasion of Northern France on June 6, 1944, succeeded, and troops advanced inland thanks to the help of the large naval bombardment force positioned off the coast. On June 25, 1944, a naval task force was sent to Cherbourg, France, to destroy the large-caliber coastal guns that could prevent the Allies from taking the much-needed port. The USS TEXAS (BB-35), a World War I veteran, was steaming towards the objective, carrying a crew of over 1,600 men. Engaging with the battery, the battleship was hit twice by German fire, resulting in several injuries and the ship’s only combat fatality. As enemy shells continued to straddle the ship, one sailor had noticed a rip in another sailor’s kapok life jacket, and upon further investigation, discovered a piece of shrapnel lodged in the neck piece. The life jacket had prevented the stray shrapnel from injuring the wearer, possibly saving his life without ever touching the water.

Tony said, “What did you do to your life jacket?” And I said, “I don’t know. What are you talking about?” He said, “It has a rip in it.” And, I took it off and I don’t remember anything. He started poking around and got a piece of shrapnel about that long and that wide. Still had rings on it from firing from the shore gun. And it was buried in the neck in the life jacket.John Harberthier, Jr., USS TEXAS crew member

Replacing Kapok

While kapok proved an excellent material for life jackets, the United States Navy searched for available substitutes throughout the war. Investigations were done on alternative natural materials available in the country, such as milkweed floss, wax-treated cotton, and cattail floss, which showed promise but were never used in large numbers. Even synthetic alternatives, such as fibrous glass, underwent testing and evaluation, providing favorable characteristics. Adopting a fibrous glass filler as a replacement for Navy lifesaving equipment ended the use of kapok in future life jackets.

Traveling Trunk

Today, we continue to educate the next generation through programming about the Kapok life jacket and its importance during the two World Wars. If you’re an educator interested in bringing the story of the Kapok life jacket into the classroom, see our traveling trunk program.

More Info