Artifact Highlight: Pieces of Admiralty

Posted by James Burke on September 18, 2024

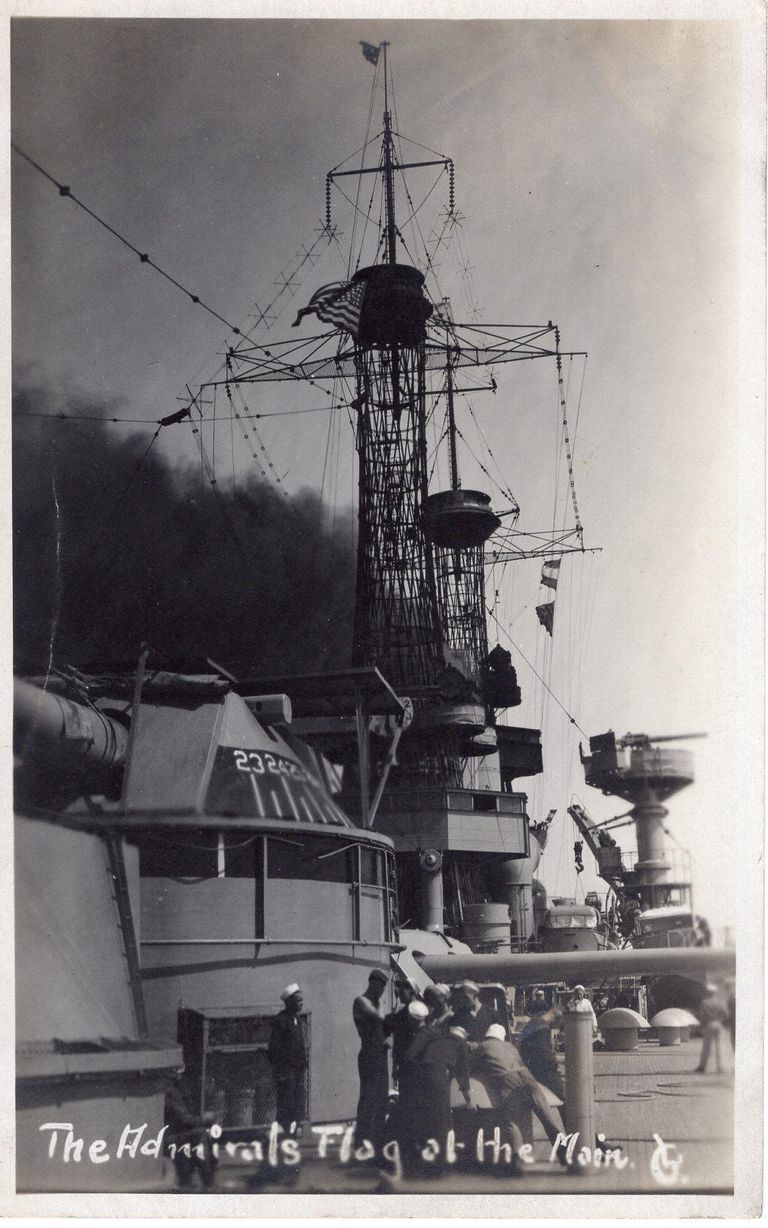

The US Navy designed Battleship Texas as a flagship. She was outfitted with a full admiral’s suite, flag bridge, and flagstaff quarters. In 1927, Texas served as the flagship of the Commander in Chief of the United States and the entire United States Fleet. She would serve in this role until 1931 and see three admirals. Henry A. Wiley, William V. Pratt, and Jehu V. Chase served as CINCUS on Texas. In 1931, Texas’s role transitioned to the flagship of Battleship Division One until 1939. Despite her age and apparent obsolescence, she maintained flagship status during World War II as head of Battleship Division Five. BatDiv5 consisted of Texas, USS New York, and USS Arkansas, where USS Nevada replaced USS New York on occasion. Texas consistently acted as the flagship of bombardment phases in several landings across the African, European, and Pacific Theaters. Often, she was part of a larger contingent of battleships, like during the Battle of Okinawa. During that battle, Texas led BatDiv5, which along with six other battleship divisions, made up Battleship Squadron 1.

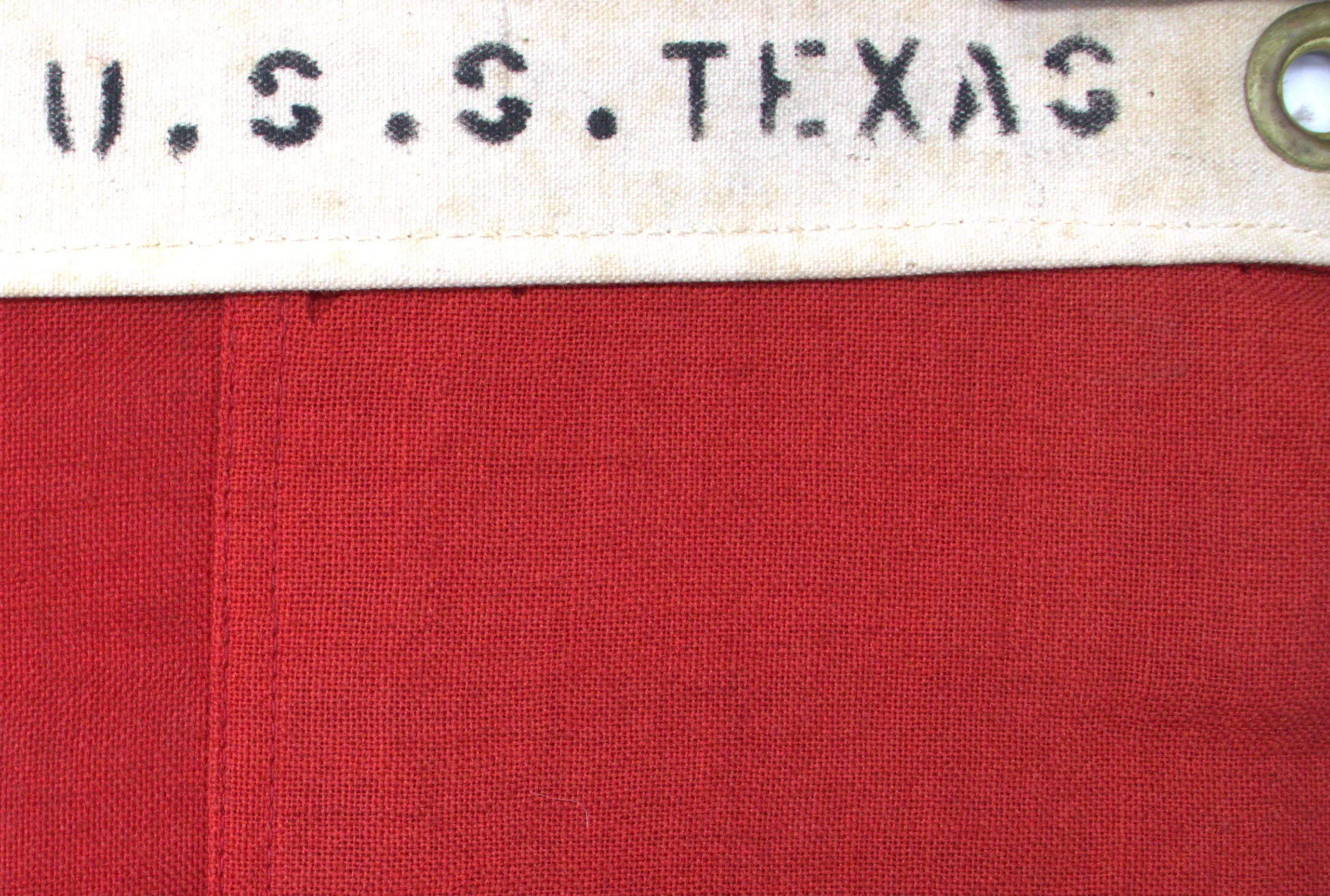

One donation received by the Battleship Texas Foundation was the flag of Rear Admiral Manley H. Simons. Simons served on Texas from June 1936 to 1937, when the Navy appointed him head of Norfolk Naval Shipyard. His flag dates to 1935 via the stamp on the trim, which would mean Simons carried the flag from his post on Mare Island in San Francisco Bay. While most admiral flags are blue, Simons’s flag is red. Red flags denote an admiral who is not the most senior of the rank in any given position in this case, the fleet. Simons was the first subordinate rear admiral of the fleet, hence his red flag. The second subordinate or non-commanding rear admiral had a white flag with two blue stars. The US Navy did away with subordinate admiral flags by the beginning of World War II.

The flag requires great care to manage and maintain. Patchwork covers the flag, indicating the fabric had degraded during its use throughout Simons’s admiralty. Apart from the degradation Simons or others repaired, several holes dot the piece. Despite the state of the fabric, repair is not recommended. The key to display and storage is stabilization rather than restoration. The patches present represent the work done to the flag while in use onboard Battleship Texas and elsewhere during the Simon’s service. Further repair would remove the authenticity the disrepair shows to viewers. The flag is stored in an aluminum shelf and lined with paper to protect the flag, similar to how we place uniform articles on paper even if put in archival boxes. Additionally, the flag should lay as close to completely unfolded as possible to avoid any creases forming in the ninety-year-old fabric.

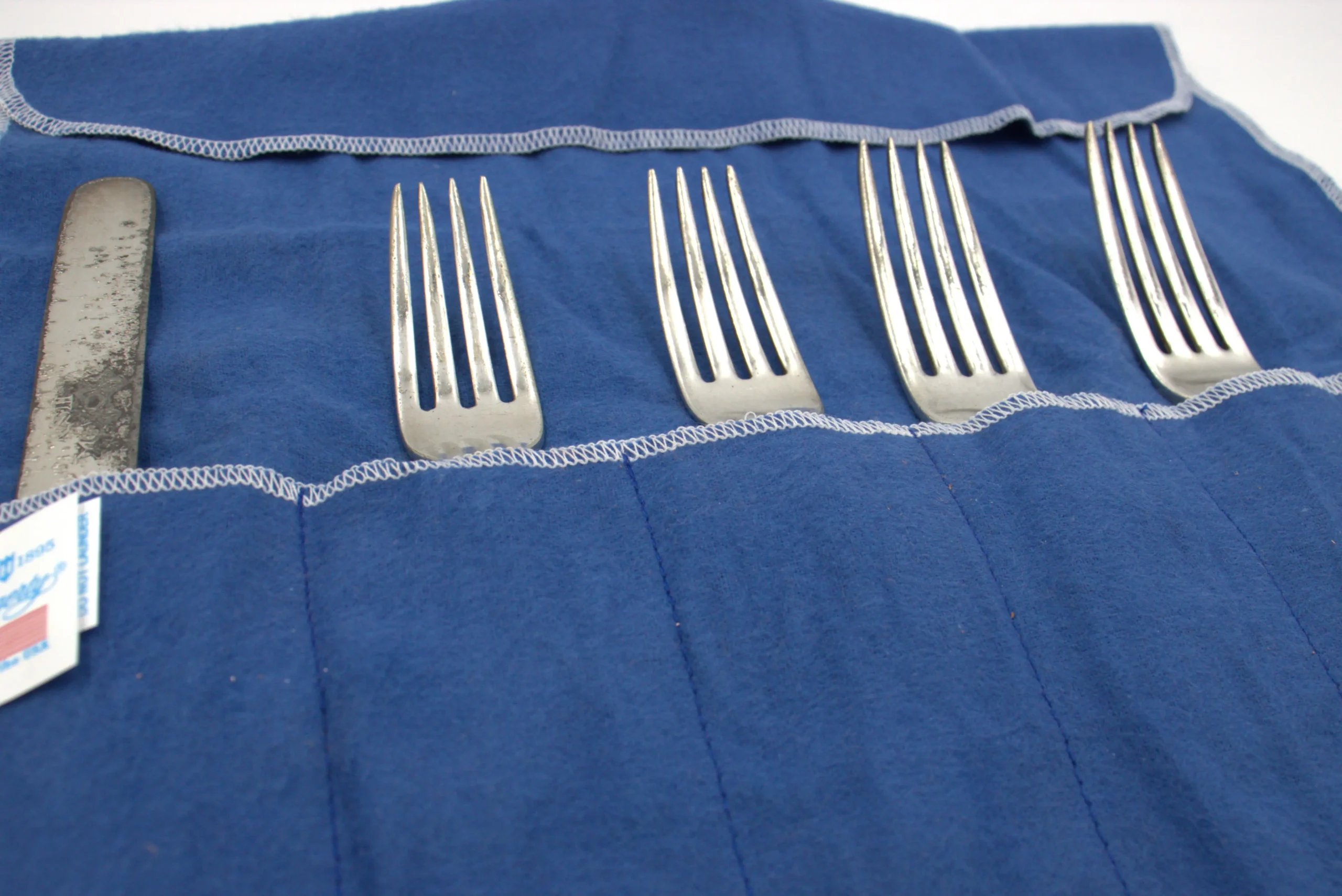

Not every symbol of admiralty was flown from the mast of a flagship. Many smaller articles of everyday life bore the signs of admiralty. In the admiral’s cabin, even the cutlery bear marks with stars to signify use by an admiral and to distinguish it from lower officers. The Battleship Texas Foundation received a collection with dozens of pieces of silverware from Stephen Nelson, a former curator of Battleship Texas when the ship fell under the management of the Texas Parks and Wildlife Department. Of the forty-seven pieces, many are marked with the fouled anchor used by wardroom officers or carry only the identifier “USN” to be used by the lower ranks. However, five have admiral’s stars on the handles. As Nelson collected these from across the United States, there is little chance they are from the same admiral, let alone one stationed on Texas. Additionally, the US Navy maintained the design of silverware throughout the twentieth century. Therefore, while difficult to date, the design is consistent with the variety used on board Texas in the admiral’s quarters and stateroom.

Silver is prone to tarnish, and thus in addition to their cleaning, must undergo a process to ensure its longevity. Handling of the silver, like with many artifacts, should be done with nitrile gloves to prevent further tarnishing, especially after polishing is completed. Polishing can take on myriad forms. Sulfur in the air forms a thin layer of silver sulfide on the surface of the silverware. Curatorial staff should apply polish, which contains an abrasive, and clean the object with a microfiber cloth. Specialized gloves that have the polish in the fabric are also usable and accomplish the same results. Cleanings should be rare since the abrasive in polish removes the surface of silver objects along with the silver sulfide. Maintaining silver is also a key factor after restoration. Items are stored in tarnish-proof cloth designed to hold silverware, with larger pieces going into bags of the same material. Anti-tarnish strips are placed in the drawer holding the silver, which reacts with sulfur-containing gases, prior to it tarnishing the silver itself.

Generous donors give new and interesting artifacts to Battleship Texas Foundation regularly. Artifacts on US Navy and Battleship Texas admiralty are rare but represent a key part of the ship and crew’s history. Battleship Texas Foundation is compiling the full history of Texas admiralty, and items like these allow a glimpse into their role and lifestyle onboard. The Battleship Texas Foundation is actively collecting historic items, photographs, and documents related to Battleship Texas (BB-35), Battleship New York (BB-34), or the other commissioned ships named USS Texas (SSN-775, CGN-39, and the first USS Texas commissioned in 1895). If you have an item that makes you say, “It belongs in a museum!” please email us at [email protected] with photos and any relevant information. Our staff is working diligently to collect, accession, and archive historical items of the Last Dreadnought.

James Burke is a History PhD candidate at the University of Houston and has worked as curatorial staff with Battleship Texas since 2020.