Artifact Highlight: Leisure & Free Time

Posted by James Burke on June 13, 2025

The men that served on Battleship Texas did more than just their military duties while on board. A large contingent of the crew enjoyed their free time writing home, doing arts and crafts, or reading. Solitude aside, most of the crew participated in group activities throughout the ship. Robert L. Ripley wrote about the 1917 Texas crew in The Houston Post, “over 50 percent of the men were members of some athletic teams.” Sports did not occupy the crew in isolation. Large crowds gathered onto any surface they could fit during events, performances, and film screenings. Despite the limited space, the crew found myriad ways to entertain themselves. While servicemen experiences are frequently conflated with their rate onboard, they participated in many crew member organized activities, sailor-founded teams, and group outings that gave a break from their Navy duties.

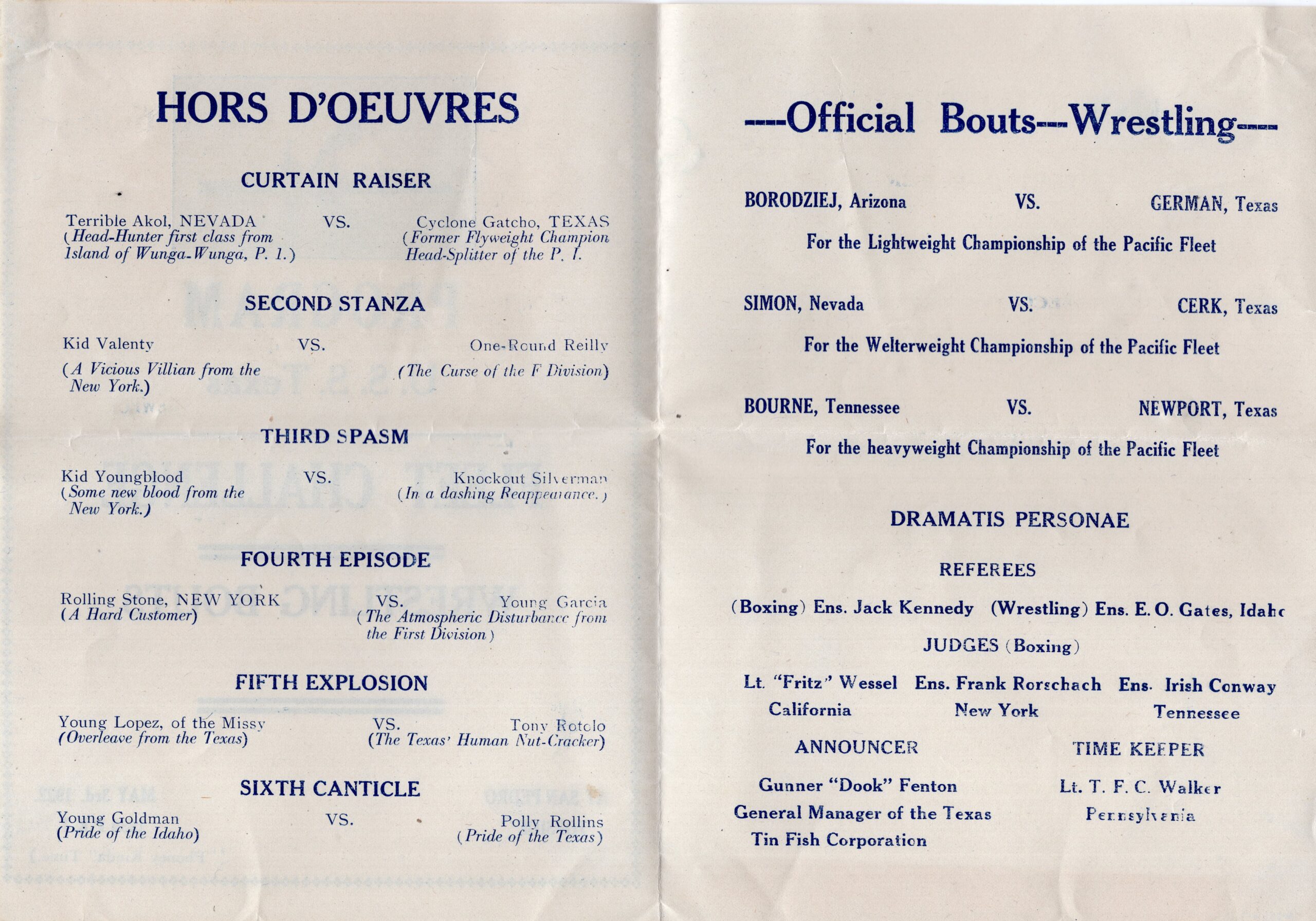

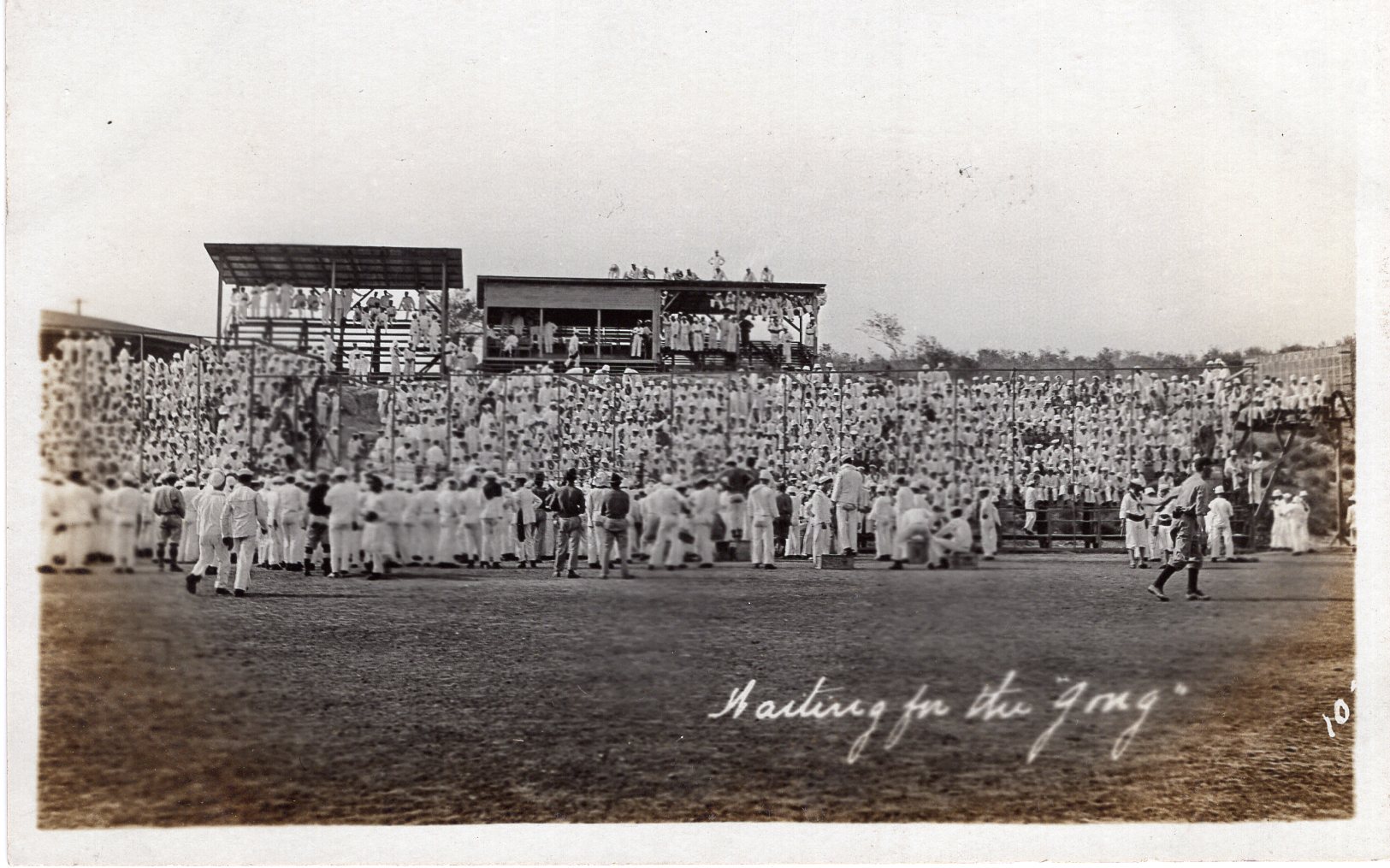

Sports were a particularly popular activity crew members could enjoy in their free time. Texas had fighting contact sports like boxing, wrestling, and spar fighting, along with traditional team sports such as football, baseball, and rowing. All sports fell under management by an officer and had specific rules on team composition. While it was a component of free time, sporting activity was regimented similarly to the rest of life on the battleship. A key benefit to the structure was an easy avenue for inter-ship competition. On May 3, 1922, the official Fleet Challenge contest for the Pacific Fleet was held for wrestling and boxing on Battleship Texas. Of the nine listed fights, six were against men from Texas, including the three weight class championships. In 1930, a similar championship was conducted for the United States Fleet in Cuba, wherein the only representation Texas had was a lone medical officer supervising the contest. In the same year however, the rowing team won the All-Navy Championship. A photograph owned by Orville Johnson and signed by all team members made its way to the Foundation’s collection.

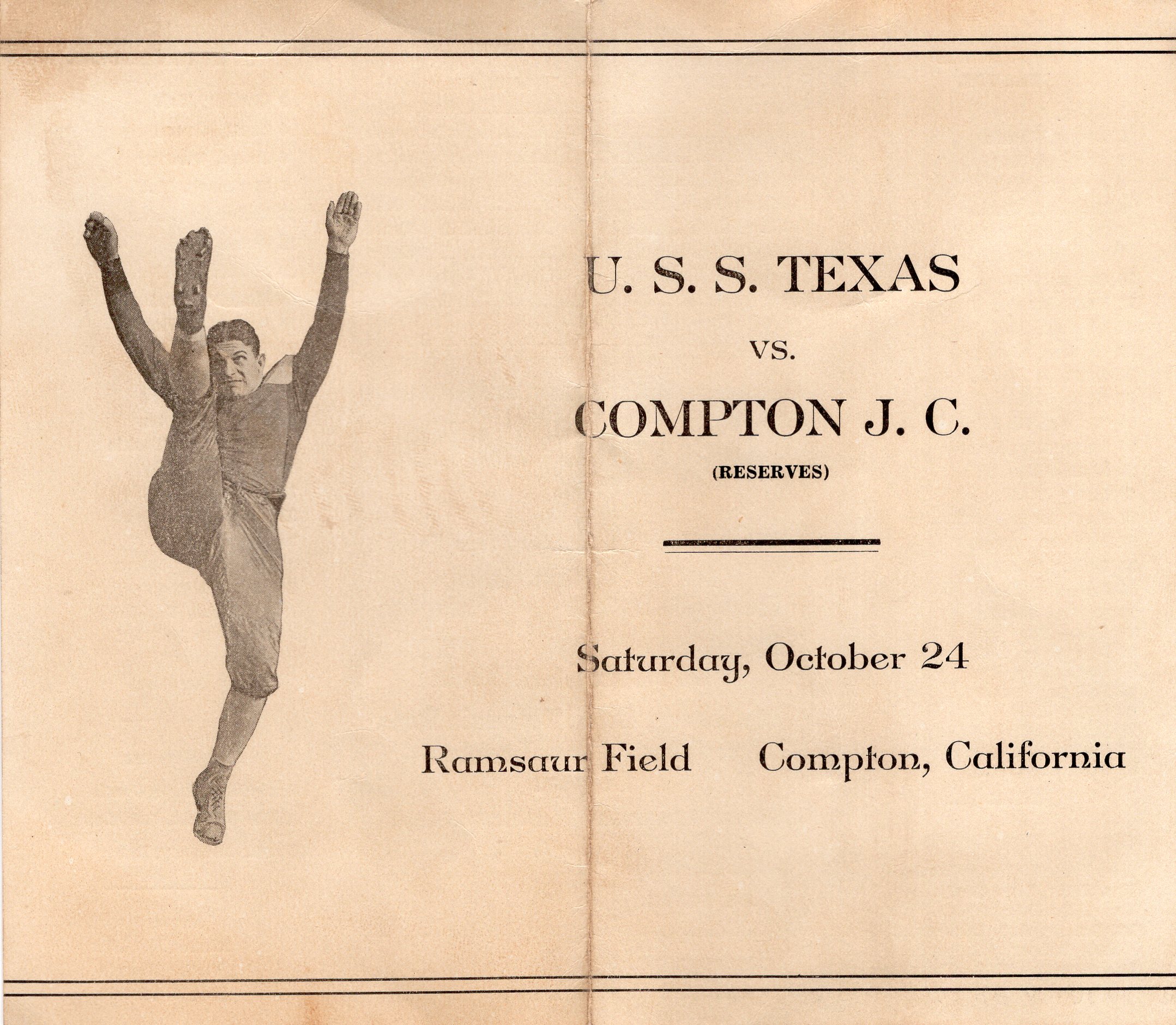

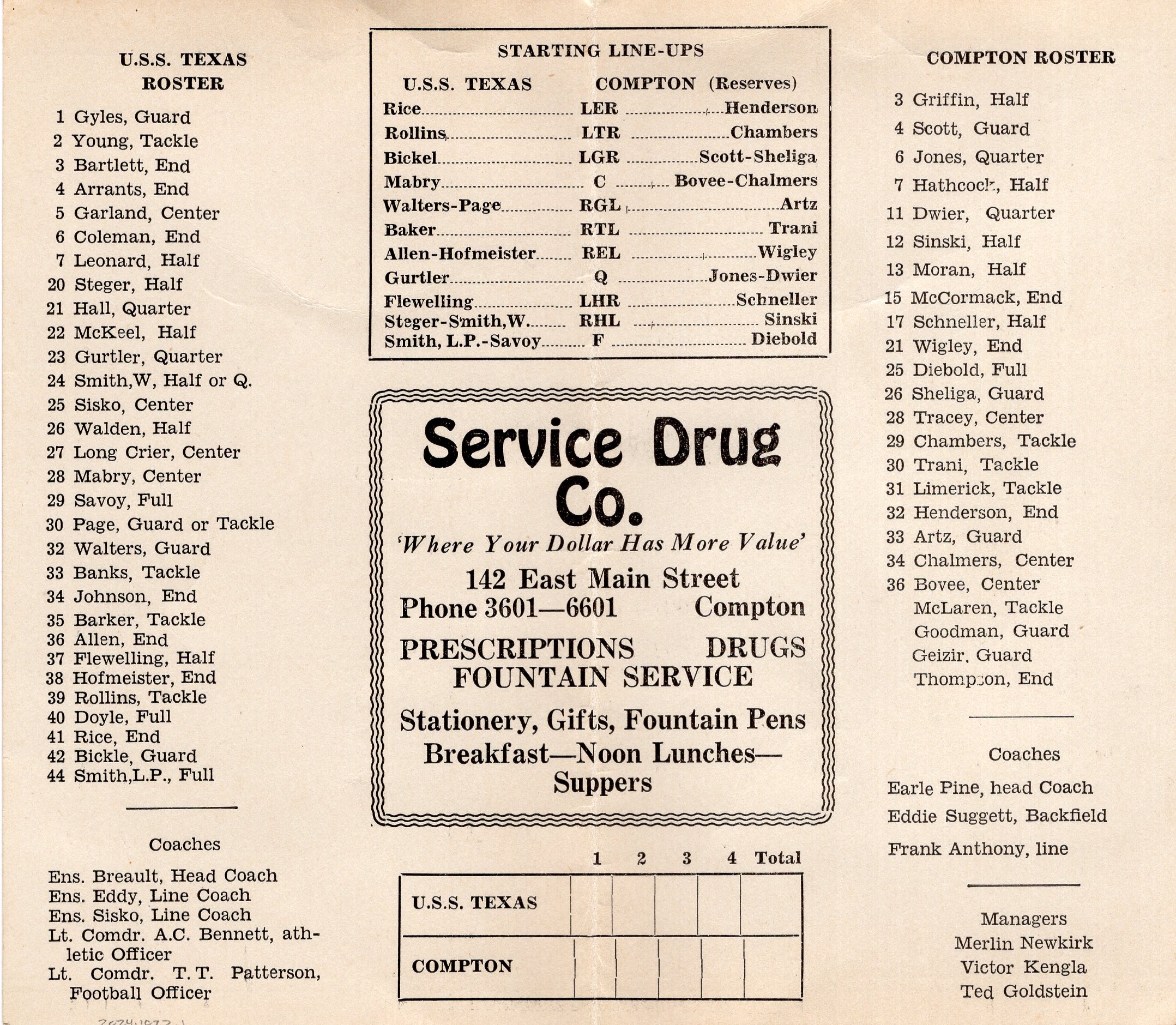

Competition could occasionally spill beyond the bounds of the US Navy. Texas’s football team of thirty men with five coaches faced off against Compton Junior College’s twenty-four with three coaches early in their 1931 season. Unfortunately, not every athletic bout ended in a Texas victory. Another program in collection from Compton Junior College revealed the less-than-stellar game performance of Battleship Texas as Compton’s team soundly beat their challengers 37-6. While competition beyond the bounds of the Navy certainly existed to a greater extent, the two game programs are currently the only within collection. Results for sporting events on and off the ship were frequently reported on the backside of crew member published papers like The Texan (1920-1924) or The Texas Steer (1924-1934). As with all paper items, they can be handled by trained staff without the use of protective gloves.

Other methods of contest existed for the men of Texas. It was a common sight to see several people huddled around a game board. One example of this-and recently donated to the museum by surviving family-is the cribbage set of Charles Pratt. Only nine of the set’s pegs survived to donation. Each is wrapped in archival paper and stored with the board. The board and pieces are placed in archival boxes aside the rest of the Pratt Collection. The wood structure carries unique challenges for preservation and storage. Wood is particularly susceptible to moisture, and the size of the object can change as moisture is absorbed into or out of the wood. Likewise, the angle at which the wood was harvested from the tree can affect longevity. Most of the faces appear to be vertical cuts, which fortunately are less susceptible to water damage due to the tighter grain. Regardless of this fact, dehumidification is especially important in wood preservation. Given our collection facility’s placement close to the Gulf of Mexico, the coastal environment allows for 55-60% humidity, allowing the wood to reach equilibrium. Any more could potentially risk molding or fungal growth, while too low could risk delamination.

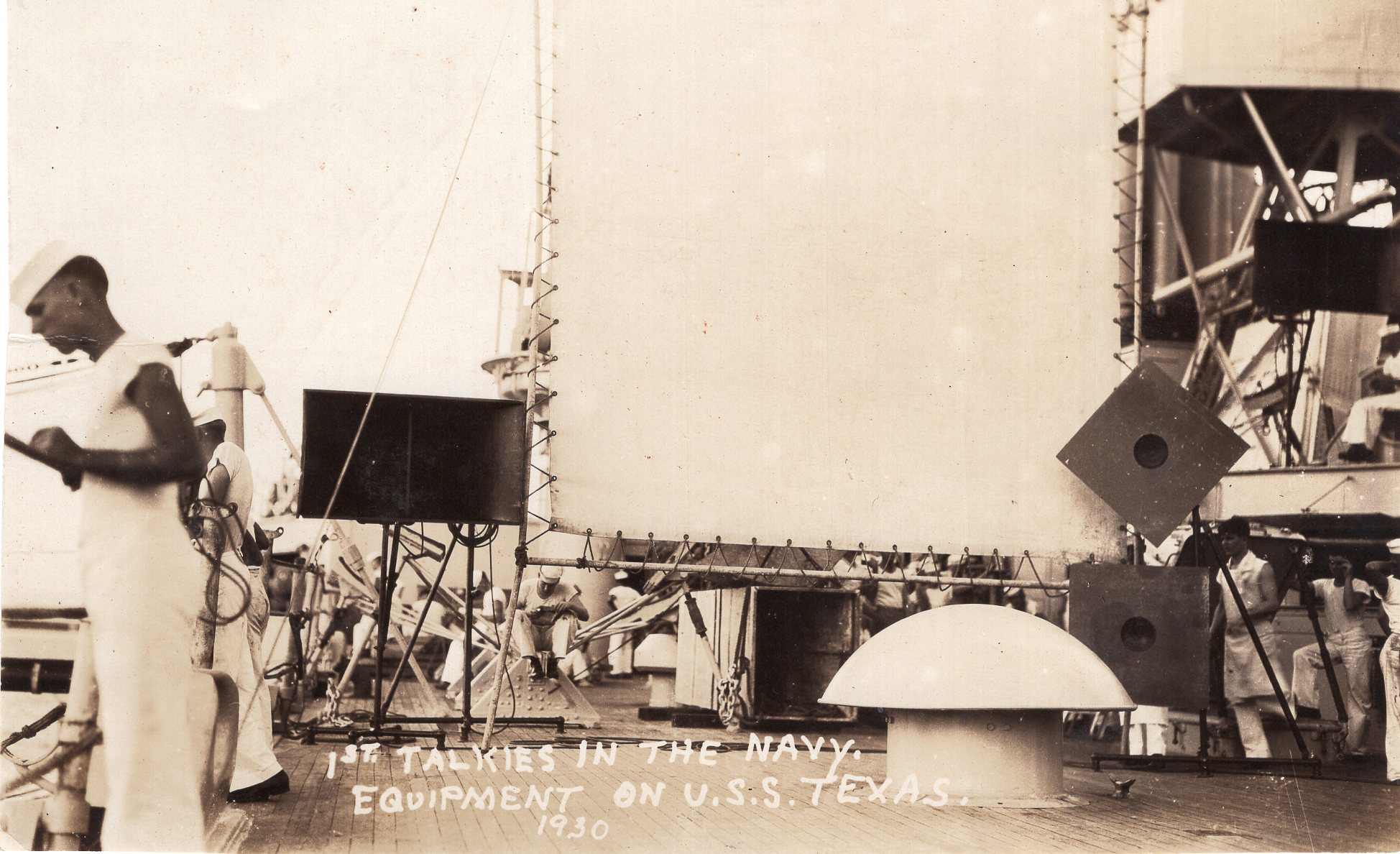

When crew members were not at contest with one another, they could relax side by side during shows and performances onboard. In fact, Texas gained some notoriety for such events. In 1930, the first talkie in the US Navy was shown on main deck aft of the air castle. A postcard donated by the Los Angeles Maritime Museum commemorates the event. Apart from movies, the fantail of the ship commonly hosted visiting performances. While a frequent spot for dignitaries and officials to address the crew, it held an entertainment value as well. A photograph from the 1930s shows performers from the Rose Parade dancing as the crew wrapped around the stern creating a sort of amphitheater. The bow tended to favor few or single performers, though often featured crew members clambering onto any higher surface for a view. Unfortunately, the only items on ship events in collection are photographs; fortunately, these photographs do an excellent job of showing crew member enthusiasm, wherever a show occurred.

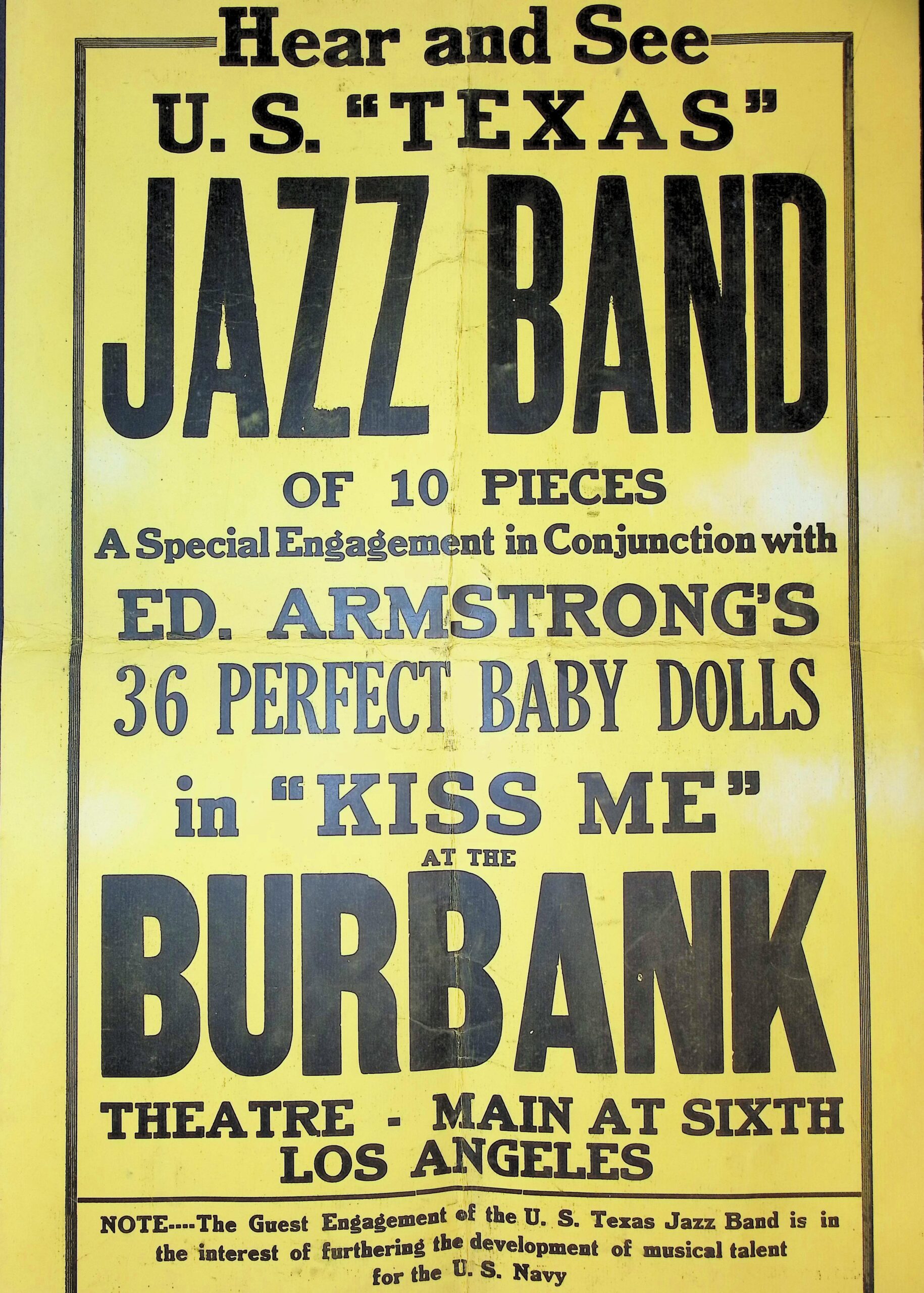

On certain occasions, performances were conducted by the crew, rather than visitors. The band often played onboard, with location varying with each performance. Sometimes, they could move off the ship entirely. The band played in concert halls, pavilions, parades, or any number of public venues when the ship made port. Crew members were encouraged to attend. Our best examples of such concerts come from Lawrence J. Gaddis, a Musician 1st Class during the early 1920s. His collection contains many items pertaining to these musical events such as tickets, flyers and other ephemera. The most impressive is a large yellow poster for the U.S. “Texas” Jazz Band. Preservation of the poster, while cumbersome due to size, is relatively simple, and no more arduous than regular paper documents. Above all, keep the paper dry.

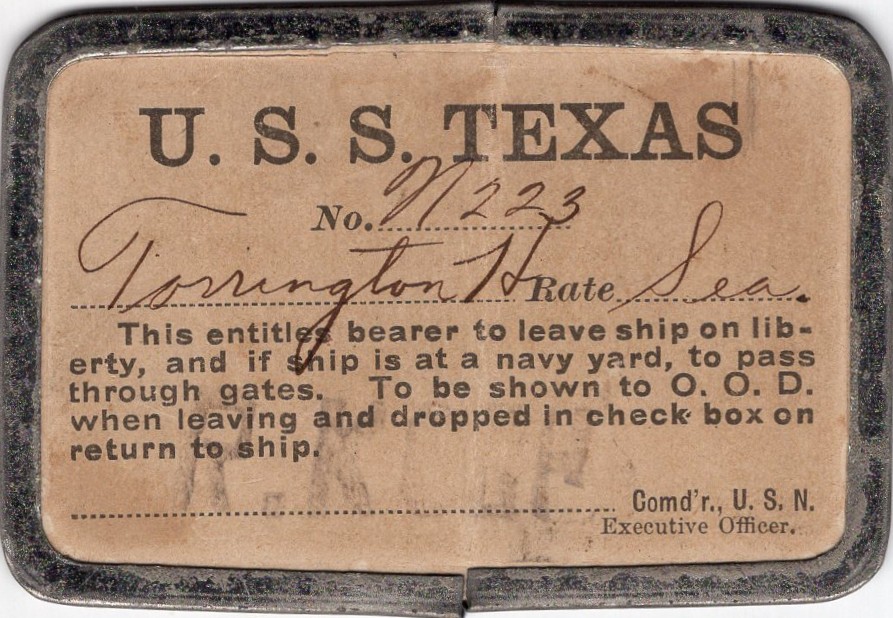

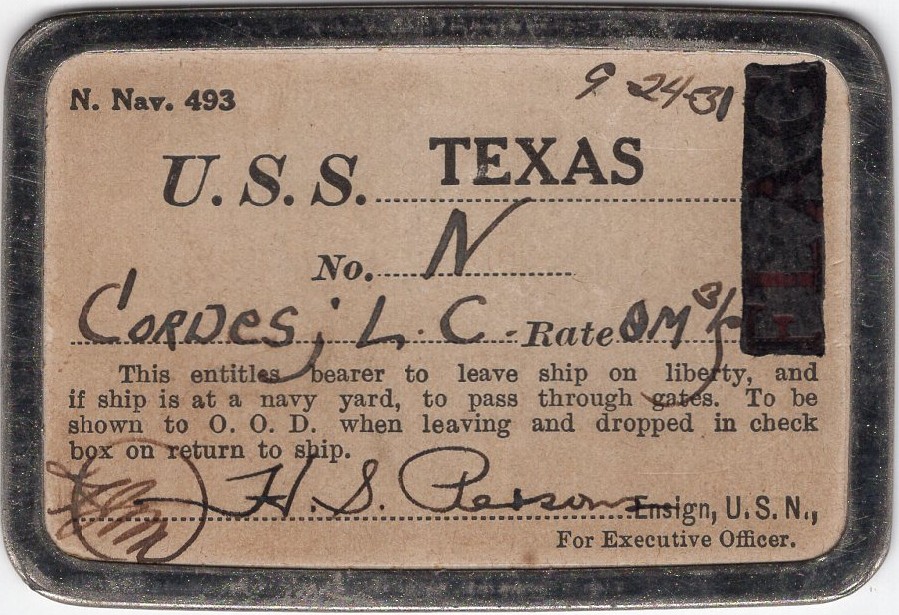

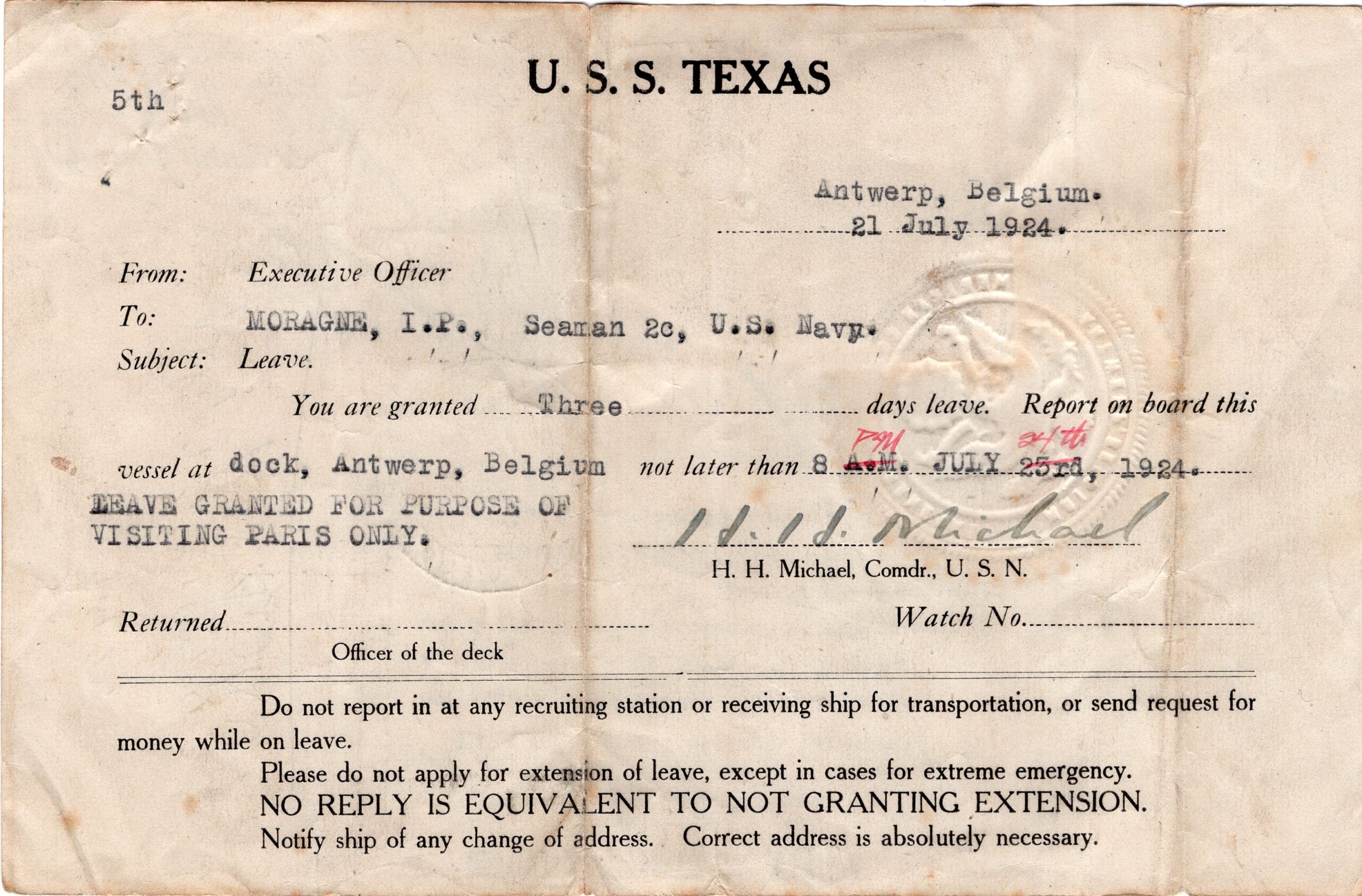

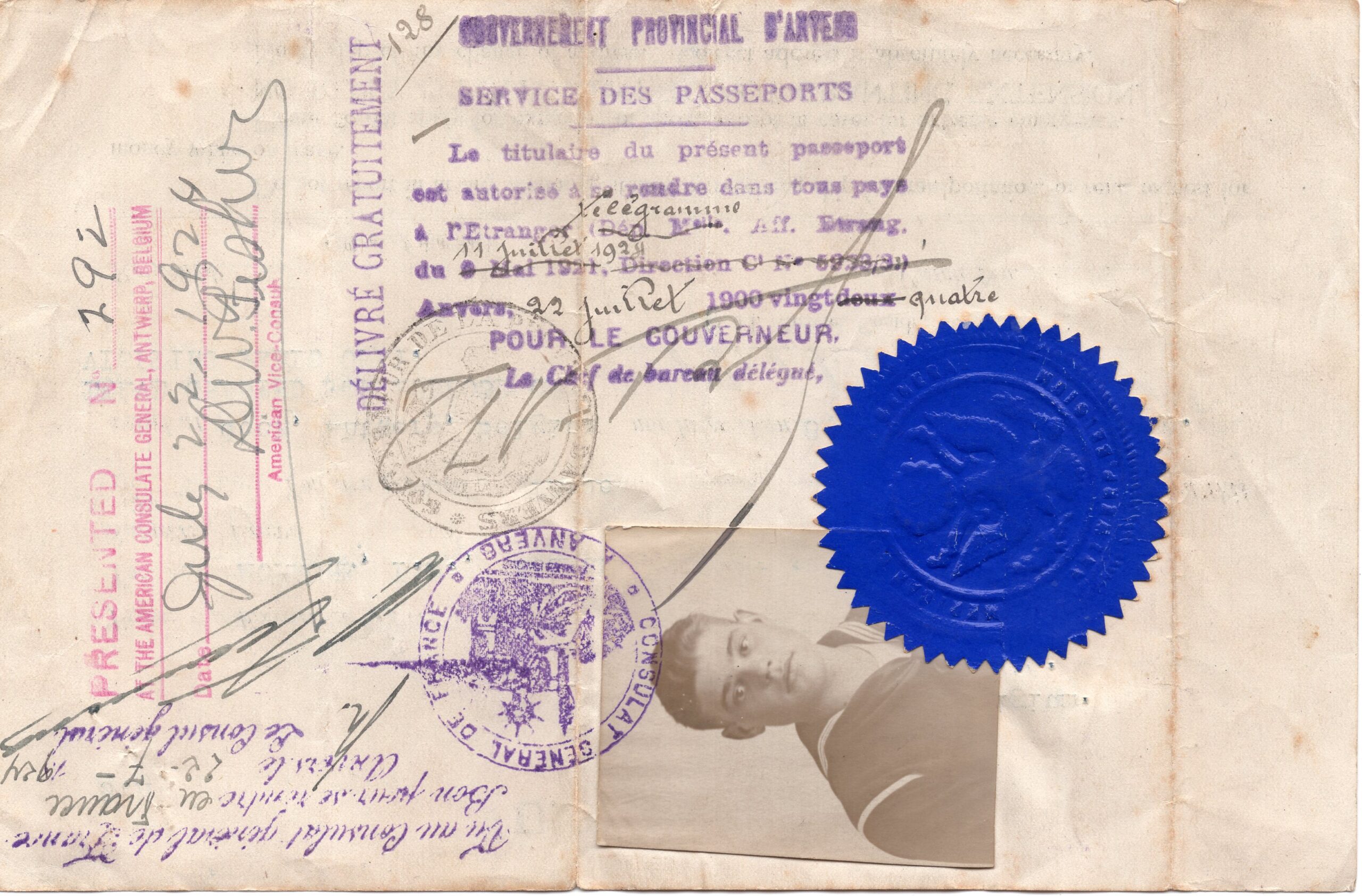

As indicated previously, many men elected to spend available time off the ship. Allowance for departure required specific documentation. These came in the form of liberty passes – two of which exist in collection, one from 1920, and the other from 1931. An officer would sign or stamp a pass with the name and rate of the requesting party written in provided blanks, granting a personalized ticket off the ship. While permission was granted frequently, it was not guaranteed. According to the deck logs, when Texas was moored in New Orleans for the 1930 Mardi Gras celebrations, officers found seven men guilty of absence without leave, four of which were found in the possession of stolen liberty passes. Each pass was framed in a light metal, which has remained largely undamaged on both. With the benefit of no corrosion, storage bears less concerns of further damage and can follow the same guidelines for paper storage. A larger Leave Pass covered longer outings and allowed sailors to visit home and acted more like a passport than a ticket.

Generous donors give new and interesting artifacts to Battleship Texas Foundation regularly. Sailor and Marine leisure free time activities show a side of military history not often witnessed or considered much by the general public. While crew members are often conflated with their service, time onboard featured games, sports, outings, and any manner of personal entertainment. The Battleship Texas Foundation is actively collecting historic items, photographs, and documents related to Battleship Texas (BB-35), Battleship New York (BB-34), or the other commissioned ships named USS Texas (SSN-775, CGN-39, and the first USS Texas commissioned in 1895). If you have an item that makes you say, “It belongs in a museum!” please email us at [email protected] with photos and any relevant information. Our staff is working diligently to collect, accession, and archive historical items of the Last Dreadnought.

James Burke is a History PhD student at the University of Houston and has worked as curatorial staff with Battleship Texas since 2020.