Lighting The Torch

The question was: where should the Allies begin their joint campaign? Land in France to liberate Europe and relieve the Eastern Front? Or in Norway to reduce the threat to the Russian convoys? President Roosevelt and British Prime Minister Churchill finally agreed on landings in Morocco and Algeria. Landing in French colonial territory, the Allies could finally defeat Germany's Afrika Korps, secure the Suez Canal and connections to Britain's empire, and support the Free French leader Charles De Gaulle. Important lessons would be learned for the future landings in Normandy.

Not everyone agreed: General George Marshall and Admiral Ernest King believed Torch would be a distraction from the real objectives of defeating Germany and Japan. World War II had been declared to demolish empires, not defend them. General Eisenhower, in command of Torch, was not sure that this 'desperate undertaking' would succeed. Two huge fleets were formed for the landings at Oran, Algiers and Morocco. The next convoy of aid to Russia had to be postponed to provide enough ships. New tactics and different types of landing craft had to be developed very quickly. Controversially, British warships had attacked the French Navy in 1940 to prevent Germany capturing its vessels. Several ships were sunk and many French sailors killed. No one knew if the Vichy French forces would oppose the Allied landings. The real aim was to overcome Axis forces in the North Africa: Torch's planners stated: 'The defeat of the Vichy French is only a means to an end.'

Crossing The Atlantic

A key piece of this plan was to move two substantial invasion forces to the coast of French North Africa without being spotted. A mostly British force left from Britain in October 1942 and headed for the British naval base at Gibraltar. The other invasion force – Task Force "HOW" or TF 34 – was an all-American force consisting of over one hundred American ships.

TF 34 was a hastily put together mix of some of the oldest ships in the US Navy, like Battleships Texas and New York, new ships like Battleship Massachusetts, and everything in between. Many of the sailors had never been to sea before, even more had never seen combat. Some ships drilled hard, multiple times a day to prepare their crews, others did not.

So many ships would be difficult to move out of any single port at once, so TF 34 was split in four and left from different ports to meet in the Atlantic. Once regrouped, the ships were spread out over an area 26 miles long and 16 miles wide. The biggest concern was encounters with German submarines or "U-Boats", but TF 34 took all manner of precautions. Neutral aircraft sighted at sea were to be shot down and neutral ships were to be boarded and sent to the nearest Allied port for the crew to be detained, all to ensure the secrecy of the Task Force's movements.

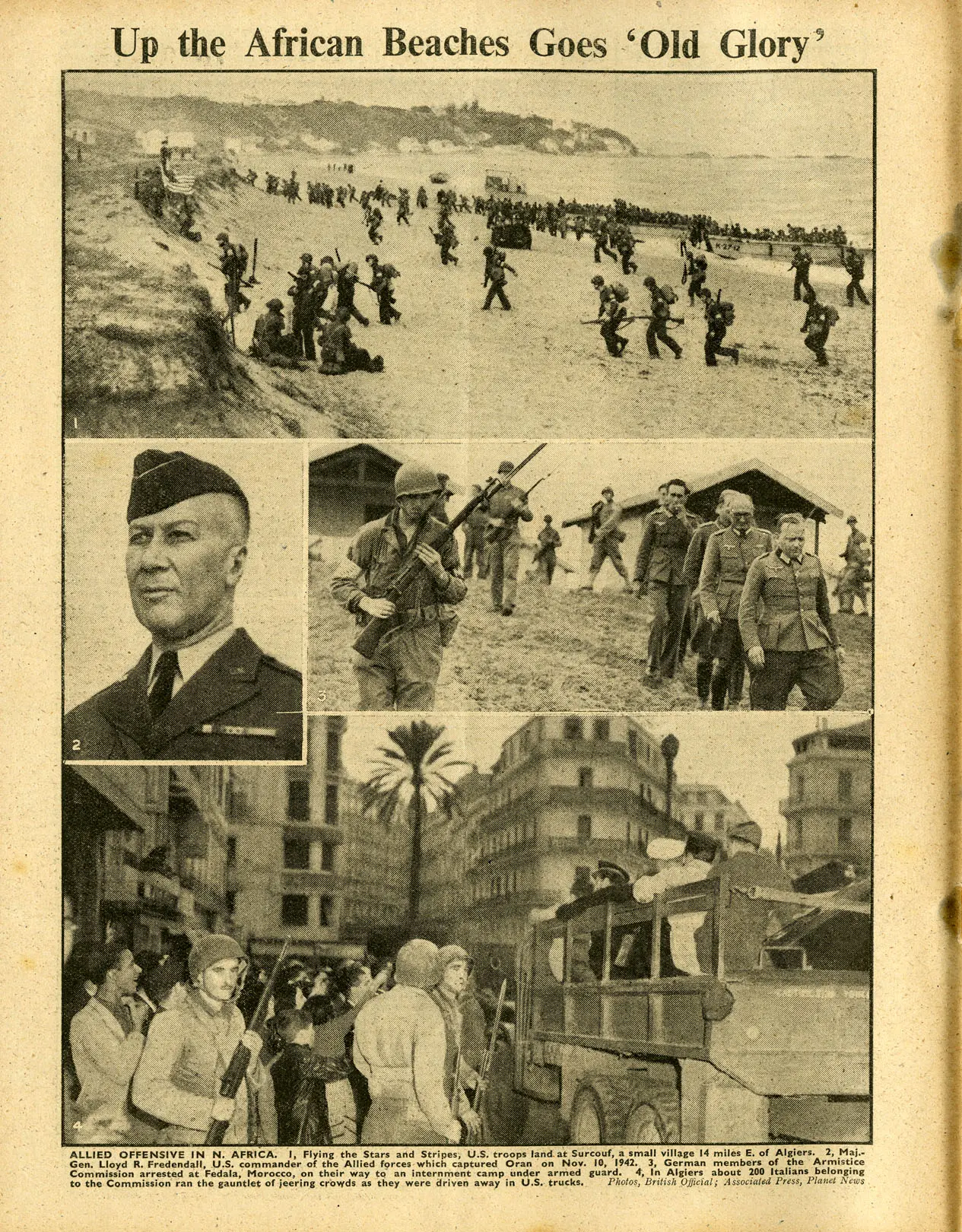

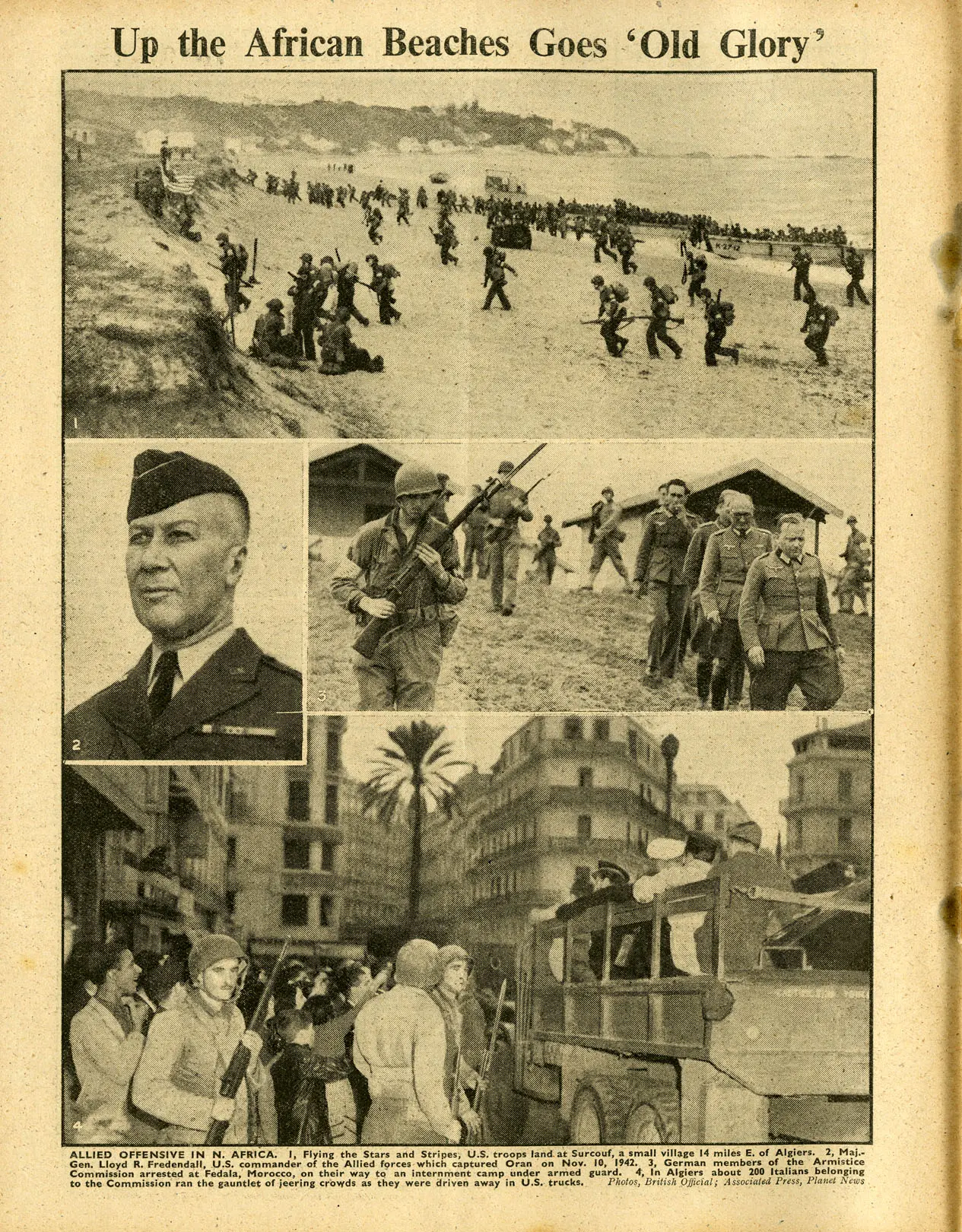

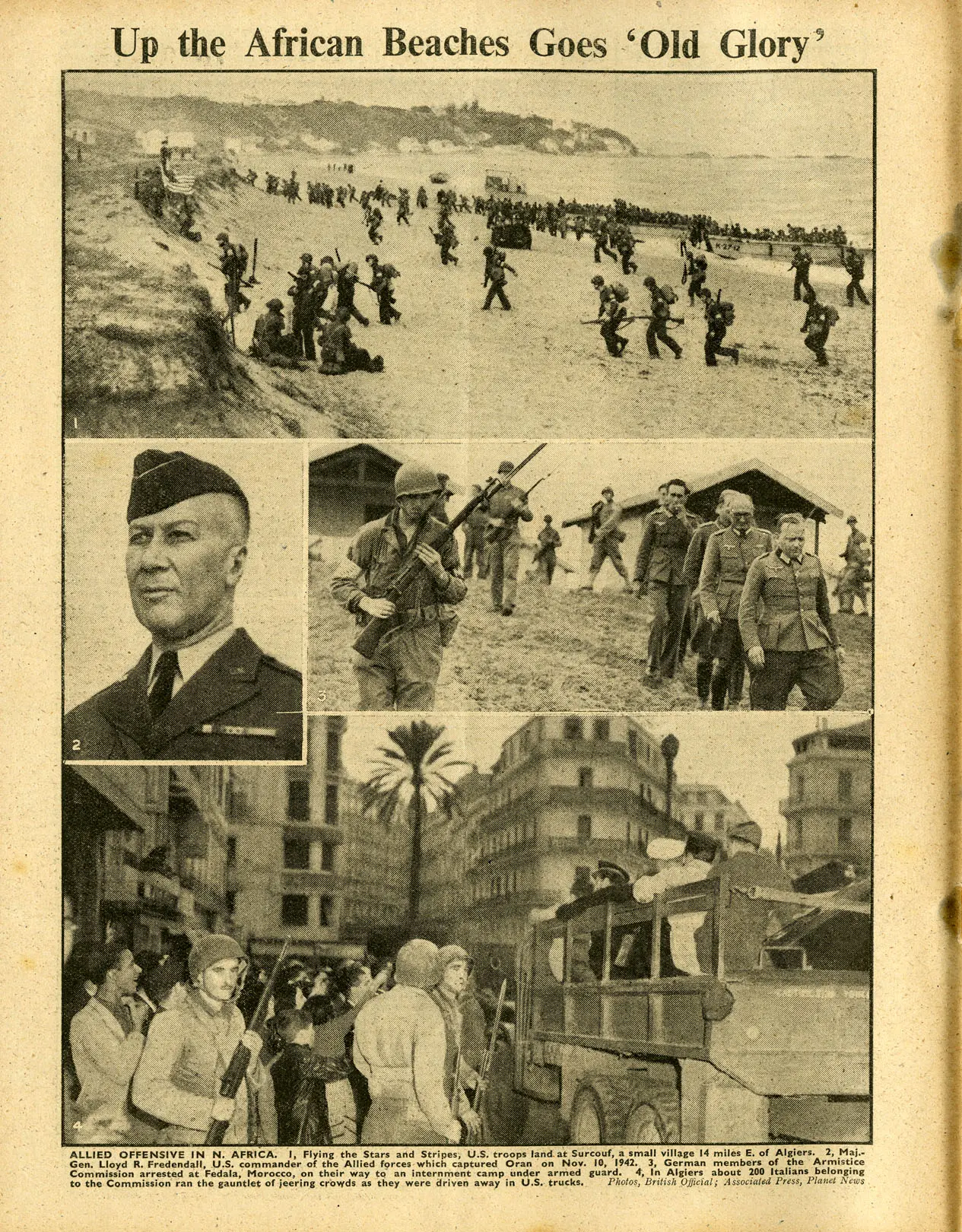

Up the African Beaches Goes 'Old Glory'

ALLIED OFFENSIVE IN N. AFRICA. 1, Flying the Stars and Stripes, U.S. troops land at Surcouf, a small village 14 miles E. of Algiers. 2, Maj.-Gen. Lloyd R. Fredendall, U.S. commander of the Allied forces which captured Oran on Nov. 10, 1942. 3, German members of the Armistice Commission arrested at Fedala, Morocco, on their way to an internment camp under armed guard. 4, In Algiers about 200 Italians belonging to the Commission ran the gauntlet of jeering crowds as they were driven away in U.S. trucks. Photos, British Official ; Associated Press , Planet News

Citation:

Image reproduced courtesy of The University of Sheffield Library Special Collections.

Up the African Beaches Goes 'Old Glory'

ALLIED OFFENSIVE IN N. AFRICA. 1, Flying the Stars and Stripes, U.S. troops land at Surcouf, a small village 14 miles E. of Algiers. 2, Maj.-Gen. Lloyd R. Fredendall, U.S. commander of the Allied forces which captured Oran on Nov. 10, 1942. 3, German members of the Armistice Commission arrested at Fedala, Morocco, on their way to an internment camp under armed guard. 4, In Algiers about 200 Italians belonging to the Commission ran the gauntlet of jeering crowds as they were driven away in U.S. trucks. Photos, British Official ; Associated Press , Planet News

Citation:

Image reproduced courtesy of The University of Sheffield Library Special Collections.

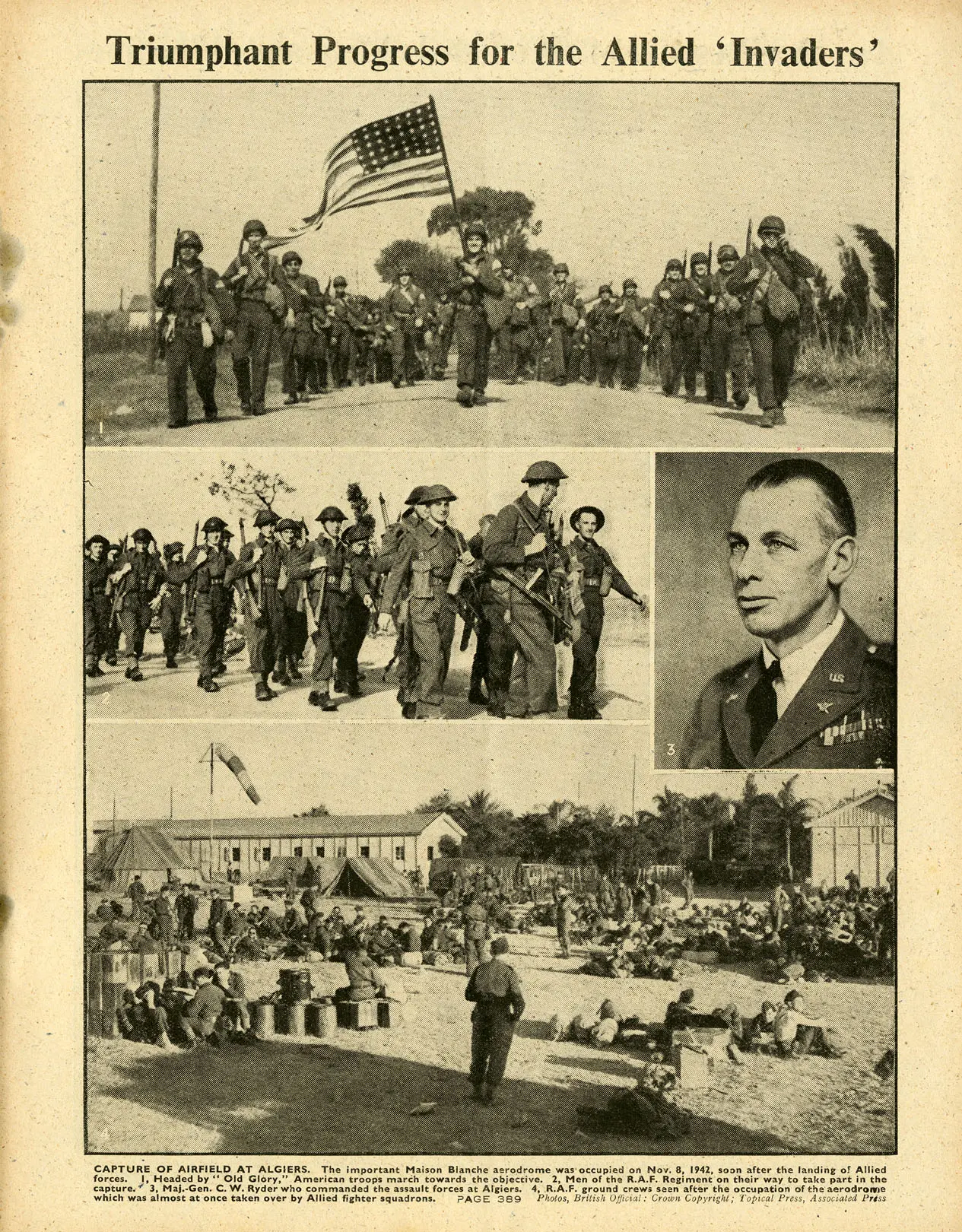

Triumphant Progress for the Allied 'Invaders'

CAPTURE OF AIRFIELD AT ALGIERS. The important Maison Blanche aerodrome was occupied on Nov. 8, 1942, soon after the landing of Allied forces. 1, Headed by "Old Glory," American troops march towards the objective. 2, Men of the R.A.F. Regiment on their way to take part in the capture. 3, Maj.-Gen. C. W. Ryder who commanded the assault forces at Algiers. 4, R.A.F. ground crews seen after the occupation of the aerodrome which was almost at once taken over by Allied fighter squadrons. Photos, British Official : Crown Copyright ; Topical Press, Associated Press

Citation:

Image reproduced courtesy of The University of Sheffield Library Special Collections.

'THE GREATEST ARMADA IN HISTORY' was no exaggerated claim for the vast assembly of ships that carried Anglo-American forces to French N. Africa. There were 850 vessels, 500 being in convoy, and as many as 350 warships escorting the expedition. Ahead of schedule the Royal Navy landed thousands of men off Algiers and Oran (more than 200 miles apart) at the same time on Nov. 8, 1942. Here is a section of the enormous convoy, seen from one of the R.A.F. Coastal Command aircraft that formed a unit in the protecting air umbrella. Air Vice-Marshal Douglas Colyer (inset) was responsible for this great air operation, in the course of which the R.A.F. flew over 1,000,000 miles and 8,000 flying hours. Photos, British Official: Crown Copyright ; Bassano

Citation:

Image reproduced courtesy of The University of Sheffield Library Special Collections.

American Invasion Convoy

View of the troop transports for Task Force "HOW" as seen from an SBD Dauntless bomber. The transports are formed into nine columns roughly in the center of the convoy, with the outermost columns led by Battleship Texas on one side and her sister, New York, on the other.

Citation:

Image provided by the National Archives & Records Administration.

American Invasion Convoy

View of the troop transports for Task Force "HOW" as seen from an SBD Dauntless bomber. The transports are formed into nine columns roughly in the center of the convoy, with the outermost columns led by Battleship Texas on one side and her sister, New York, on the other.

At the time, this convoy was one of the largest amphibious invasion forces ever assembled. Its magnitude can be easily lost when thinking of later battles, like Normandy or Okinawa. On October 24th, Walter Cronkite was briefed on the operation and had this to say in his journal "Strictly a dull Saturday at sea. EXCEPT: Admiral Kelly today told me the whole story of our operation, pointing out the scenes of activity on reconnaissance maps, charts and photographs. The scope of the movement absolutely startled me. This truly is the second front, greater in implications, more necessary of complete success than anything in which America has yet been involved. This is THE SHOW!"

Citation:

Image provided by the National Archives & Records Administration.

USS Ranger on Alert

Gun crews man two 5"/25 caliber anti-aircraft guns on USS Ranger during the convoy to North Africa.

Citation:

Image provided by the National Archives & Records Administration.

Drills on USS Santee

Santee's crew exercising on the flight deck during the convoy to North Africa.

Citation:

Image provided by the National Archives & Records Administration.

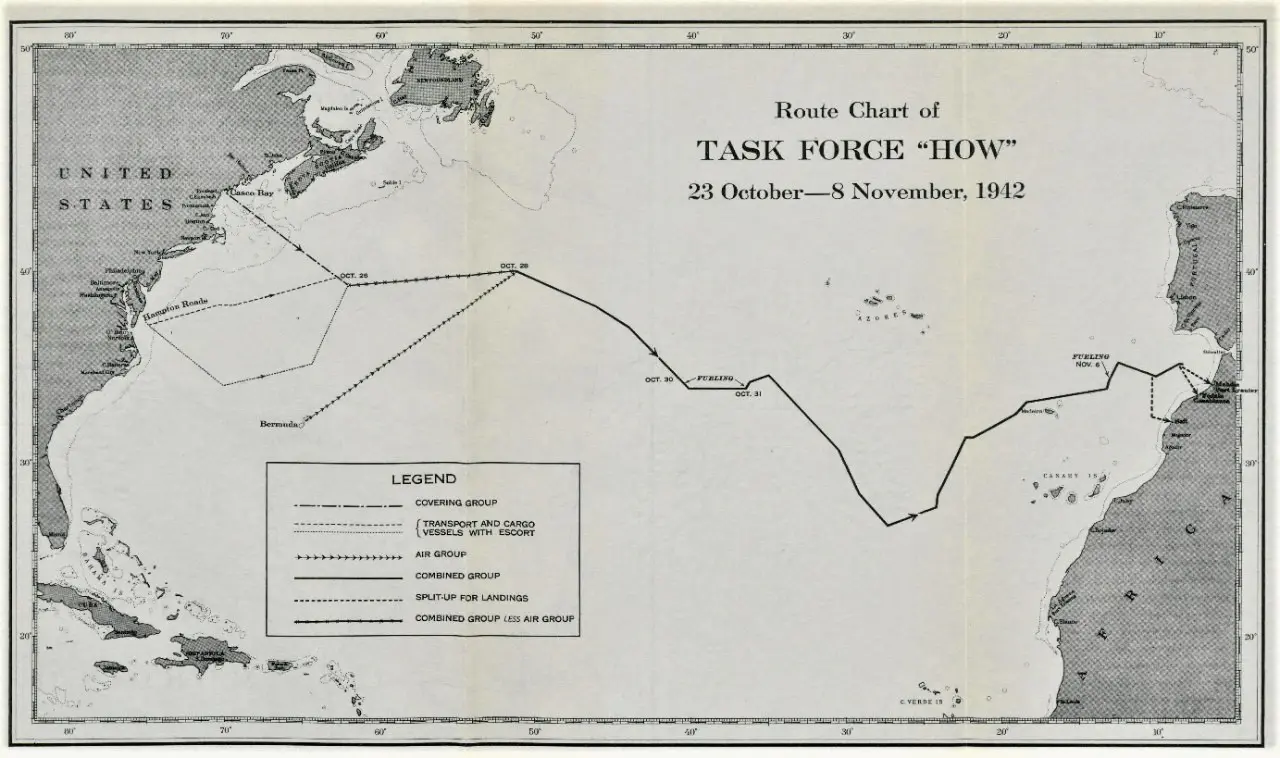

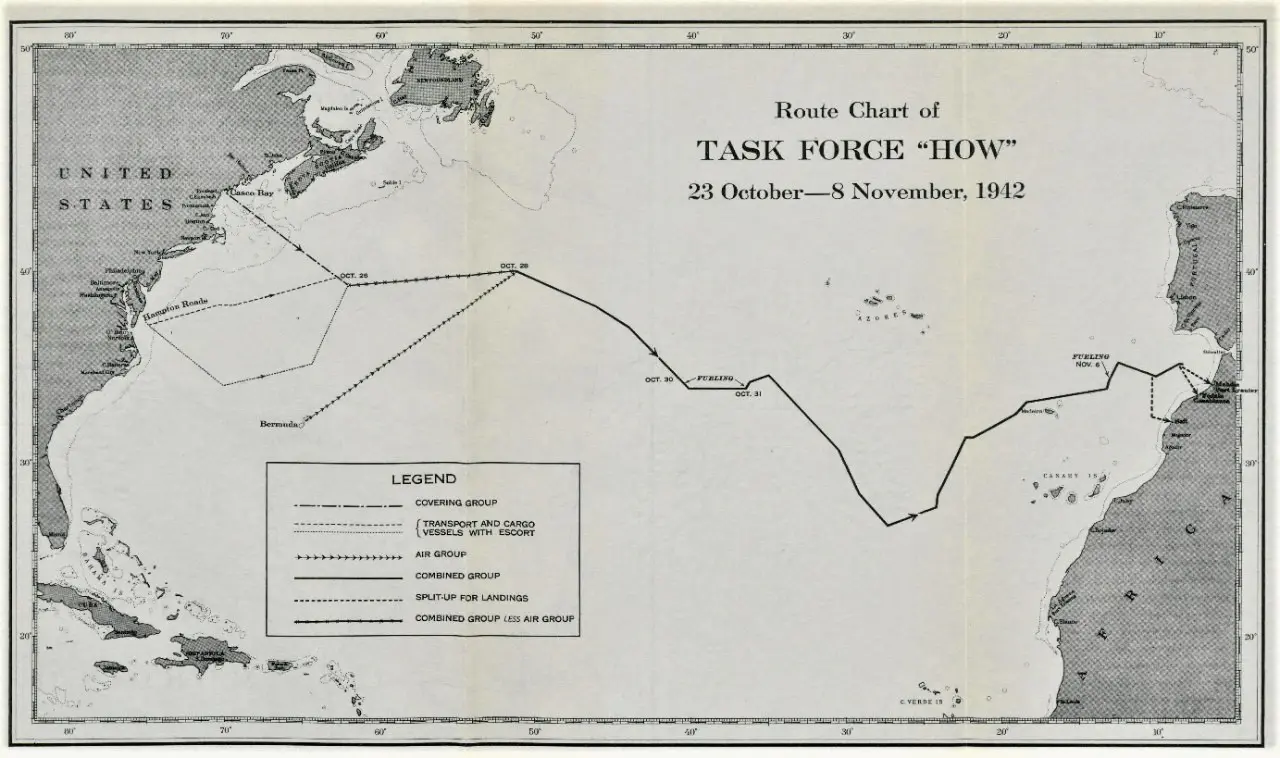

Route Chart of TASK FORCE "HOW"

23 October—8 November, 1942

Battleship Texas departed from Hampton Roads on October 23rd, taking the southerly route to Task Force HOW's meeting point. The path across the Atlantic had been carefully planned to avoid detection in three ways — this path avoided common shipping lanes which would lead to contact with neutral merchant ships, the route spent most of its time appearing to head towards Dakar in French West Africa (modern day Senegal) in case the Task Force was spotted, and particular care was taken to avoid the Azores (controlled by neutral Portugal) and the Canary Islands (controlled by neutral Spain).

The war planners had done an excellent job planning this route, at least as far as deceiving Texas's crew. Walter Cronkite was aboard for the ride as a war correspondent and made this entry in his journal "Thought I'd talk to some of the crew today just to see how they speculated about our future operations, our destination, etcetera. Consensus: 'We watch which way the ship is going,' they said, 'and we can pretty well figure out where we are bound. Before we left Norfolk we figured we were going to Martinique. They hadn't issued us any winter clothing and we saw all the transports loaded with landing barges, tanks, airplanes and stuff. Then when we started out and sailed south, we figured we were right. When we zigged northward a little bit we began to decide it was Dakar we were going to, and some of the boys even thought we might be going around to the Indian Ocean and up to Alexandria. We've got the straight dope though that there are going to 154 ships along. Then we zigged again and now we're going straight north. Damned if that doesn't confuse us.' "

Citation:

Image provided by Naval History & Heritage Command.