Armistice

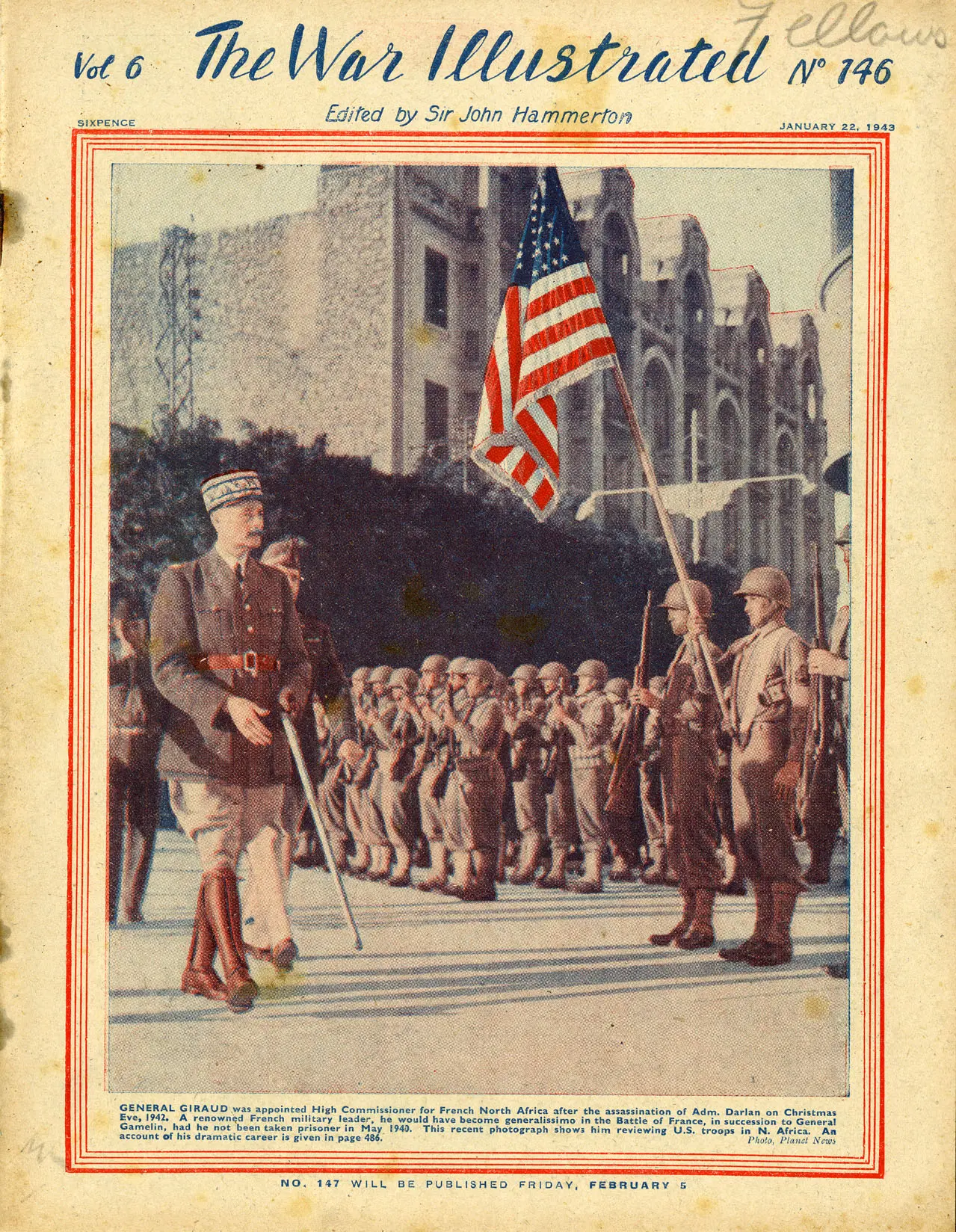

Before the invasion, the Allied war planners were looking for a collaborator — someone possibly within the Vichy government, friendly to the Allies, who could administer North Africa after the battle or even stop the French from resisting Operation Torch entirely. The Allies thought they found the man for the job, General Henri Giraud, but Giraud (to his own surprise as well) was not able to deliver on his promises.

When Giraud fell through, the Americans were forced to look for alternatives, and lucky enough, the French Commander-in-Chief Admiral (Jean) François Darlan had unexpectedly arrived in Algiers just before the invasion. Negotiations took place over four days and on November 11th, Darlan had agreed to an armistice to end the fighting in Morocco and Algeria. This deal was immediately controversial at home, but it did bring the Allies a much needed victory at a time when Germany and the Axis appeared unstoppable.

Breaking News

During Operation Torch, Battleship Texas carried a young correspondent with United Press named Walter Cronkite. Today, Cronkite is best known for his work on CBS in the 60s and 70s, but Operation Torch was a pivotal moment in his career. On November 15th, Battleship Texas left the coast of Morocco for Norfolk, Virginia. At first, Cronkite was disappointed and believed he had missed out on bigger stories by not staying in Africa. But Cronkite found a silver lining; he would be the first correspondent to return home, so he would be the first to publish uncensored stories from Operation Torch.

There was one big problem though, USS Massachusetts was also on her way home and carrying a rival reporter, International News Service's John Henry. Massachusetts was much faster and would beat Texas home without a doubt. All hope seemed lost until Cronkite spoke to one of the pilots, Lt. Fredrick Dally. Dally was due to fly off the ship early and on November 26th, Cronkite and Dally were catapulted off Battleship Texas together in a desperate attempt to beat John Henry home.

Cronkite went straight to work and wrote thirteen stories that night, and those stories went out for publication the following morning. This "scoop" proved to be a major boost for his career, but he later found out he owed that success in part to INS's John Henry. Massachusetts had beaten Texas back to the US by a week, but Henry took the week off for Thanksgiving, giving Cronkite the time he needed.

Learning from Operation Torch

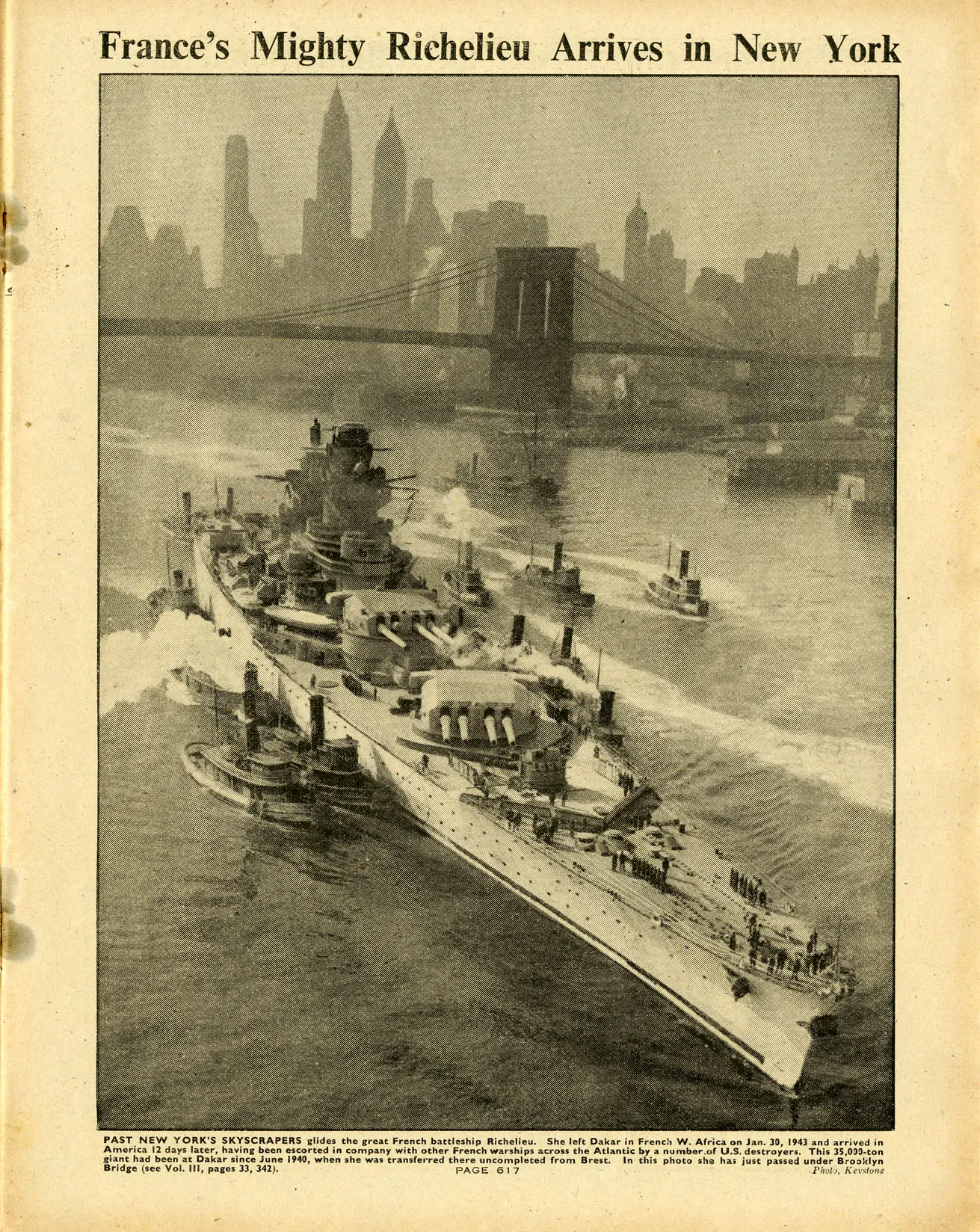

The Torch landings were successful, setting the stage for the invasion of Italy in 1943 and liberation of France in 1944. Battleship Texas supported the landings at Port Lyautey and would go on to play key roles on D-Day at Omaha Beach and in more amphibious landings in the Pacific. By 1943 more than a million and a half Americans were serving in uniform around the world. But the war would last two more years, and Torch's controversies did not go away. Torch might be easy to overlook in comparison with D-Day or the Pacific, but it highlighted tensions between Britain, America, and France, about how to fight the war and what the world should be like afterwards. To show these contradictions, the French battleship Richelieu was repaired in the United States after she and her sister ship Jean Bart had been fired upon by British and American ships. Richelieu later joined other Allied ships in the Pacific, helping to drive the Japanese from Indochina but thereby sowing the seeds of the Vietnam War.

The War Illustrated

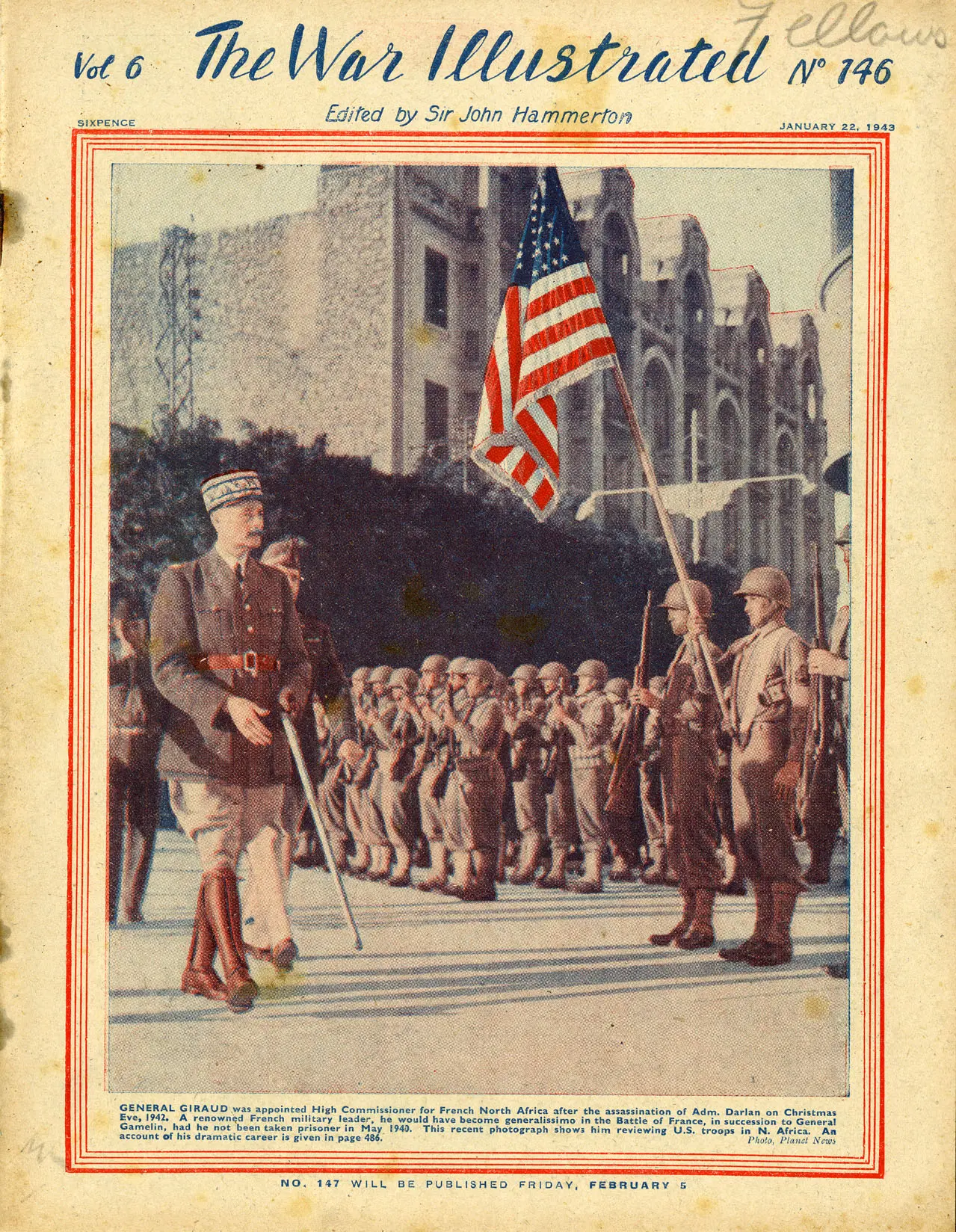

Edited by Sir John Hammerton January 22, 1943

GENERAL GIRAUD was appointed High Commissioner for French North Africa after the assassination of Adm. Darlan on Christmas Eve, 1942. A renowned French military leader, he would have become generalissimo in the Battle of France, in succession to General Gamelin, had he not been taken prisoner in May 1940. This recent photograph shows him reviewing U.S. troops in N. Africa. An account of his dramatic career is given in page 486.

Citation:

Image reproduced courtesy of The University of Sheffield Library Special Collections.

The War Illustrated

Edited by Sir John Hammerton January 22, 1943

GENERAL GIRAUD was appointed High Commissioner for French North Africa after the assassination of Adm. Darlan on Christmas Eve, 1942. A renowned French military leader, he would have become generalissimo in the Battle of France, in succession to General Gamelin, had he not been taken prisoner in May 1940. This recent photograph shows him reviewing U.S. troops in N. Africa. An account of his dramatic career is given in page 486.

Citation:

Image reproduced courtesy of The University of Sheffield Library Special Collections.

France's Mighty Richelieu Arrives in New York

PAST NEW YORK'S SKYSCRAPERS glides the great French battleship Richelieu. She left Dakar in French W. Africa on Jan 30, 1943 and arrived in America 12 days later, having been escorted in company with other French warships across the Atlantic by a number of U.S. destroyers. This 35,000-ton giant had been at Dakar since June 1940, when she was transferred there uncompleted from Brest. In this photo she has just passed under Brooklyn Bridge.

Citation:

Image reproduced courtesy of The University of Sheffield Library Special Collections.

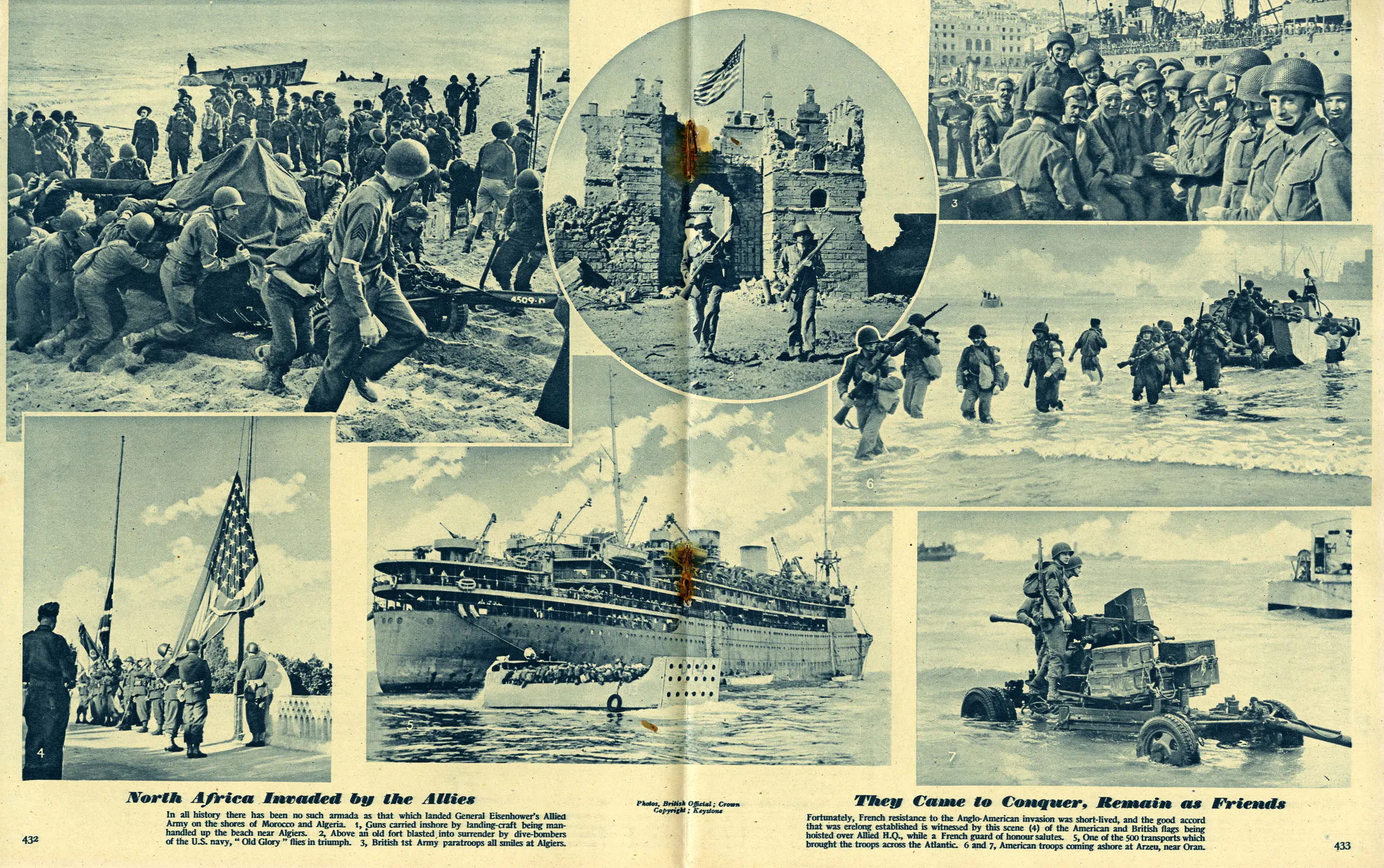

North Africa Invaded by the Allies

In all history there has been no such armada as that which landed General Eisenhower's Allied Army on the shores of Morocco and Algeria. 1, Guns carried inshore by landing-craft being man-handled up the beach near Algiers. 2, Above an old fort blasted into surrender by dive-bombers of the U.S. navy, "Old Glory" flies in triumph. 3, British 1st Army paratroops all smiles at Algiers.

They Came to Conquer, Remain as Friends

Fortunately, French resistance to the Anglo-American invasion was short-lived, and the good accord that was erelong established is witnessed by this scene (4) of the American and British flags being hoisted over Allied H.Q., while a French guard of honour salutes. 5, One of the 500 transports which brought the troops across the Atlantic. 6 and 7, American troops coming ashore at Arzeu, near Oran.

Citation:

Image reproduced courtesy of The University of Sheffield Library Special Collections.

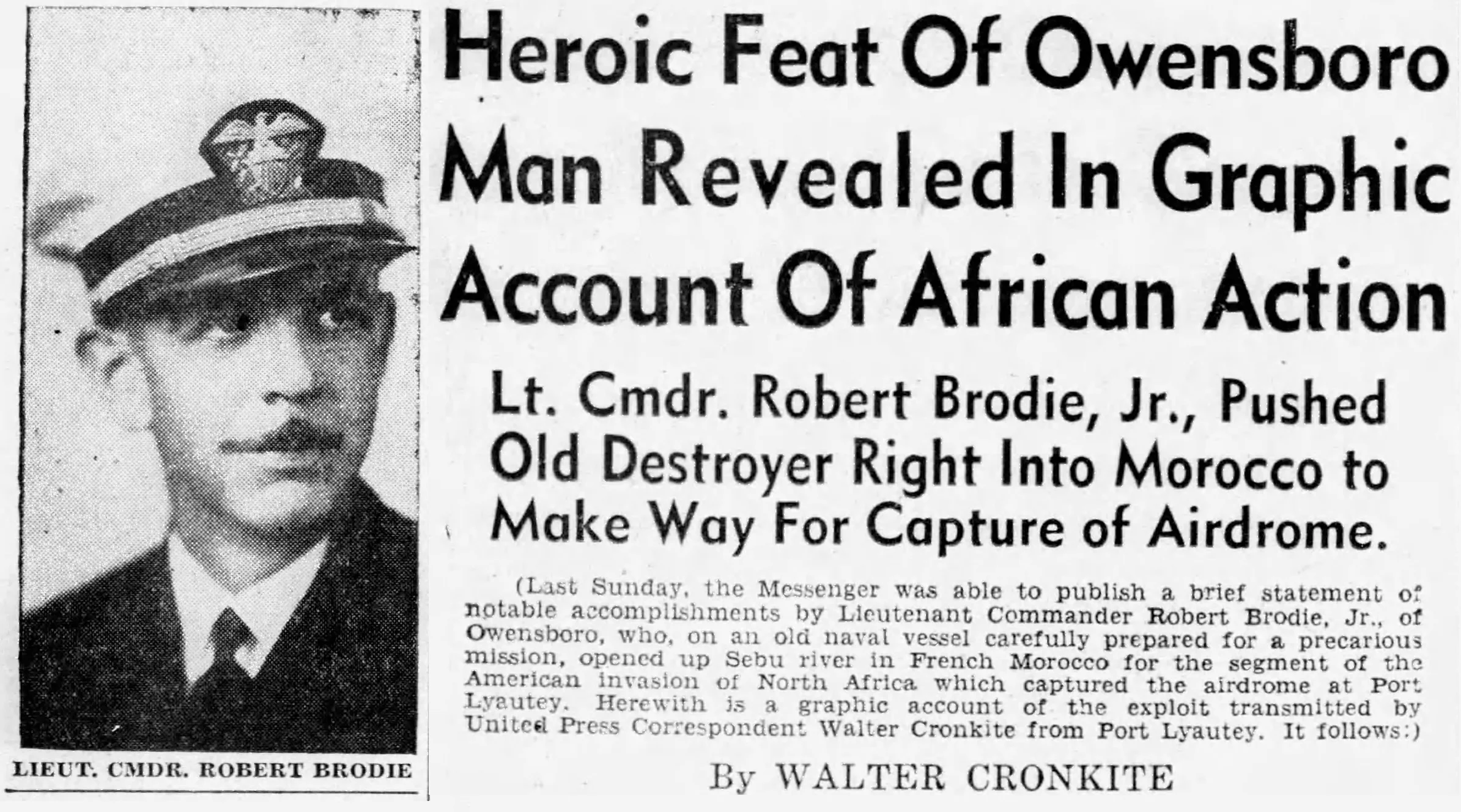

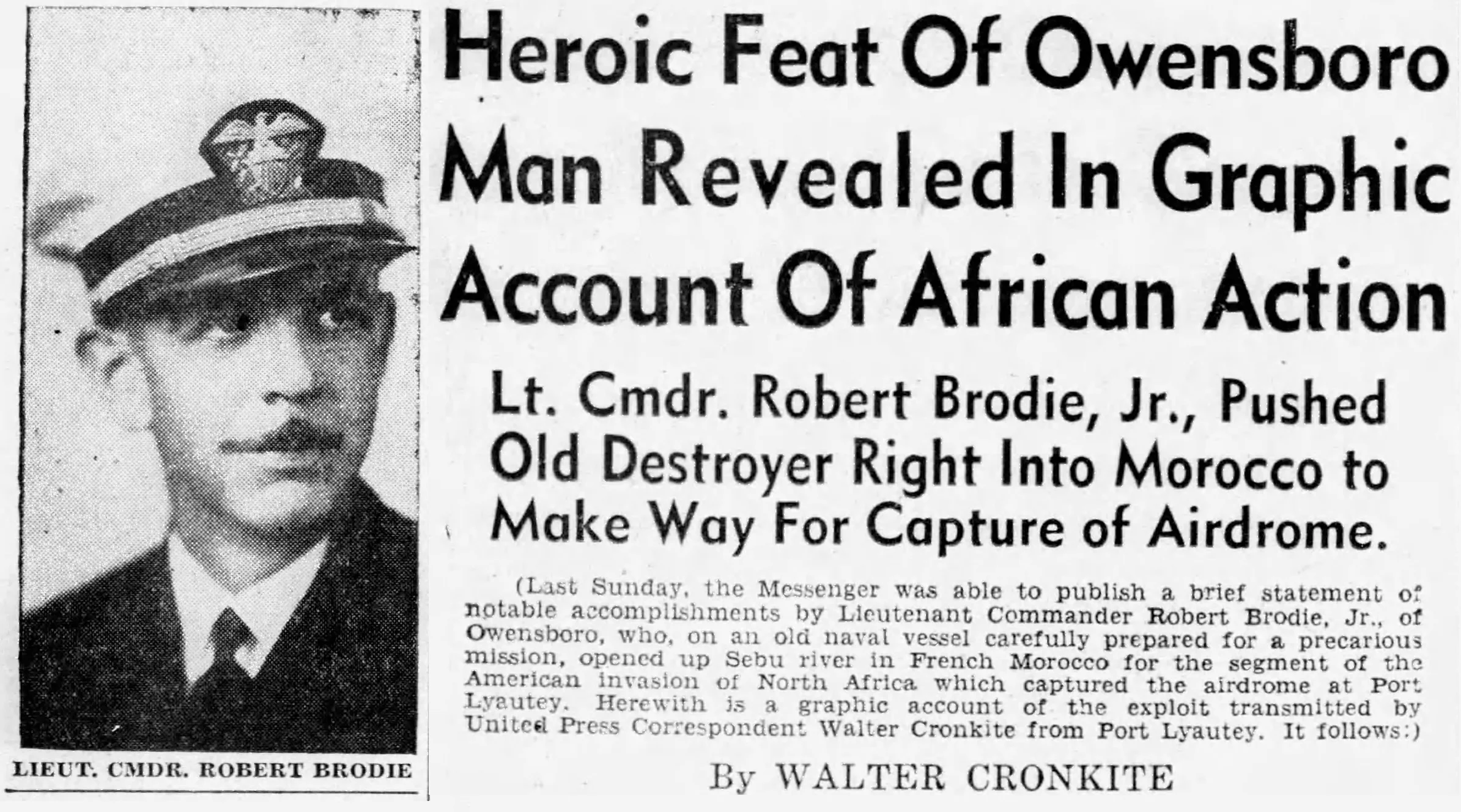

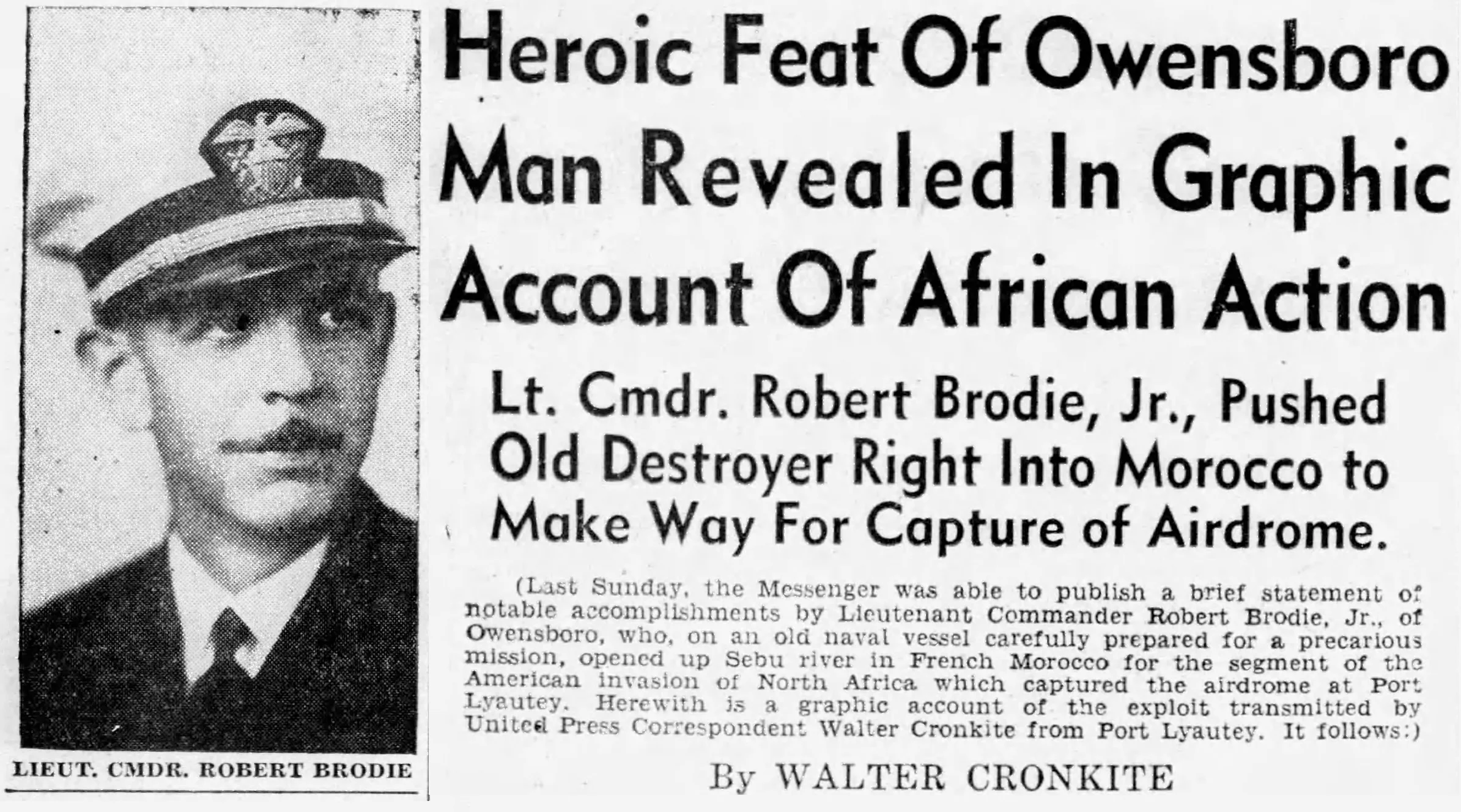

Heroic Feat Of Owensboro Man Revealed In Graphic Account Of African Action

Lt. Cmdr. Robert Brodie, Jr., Pushed Old Destroyer Right Into Morocco to Make Way For Capture of Airdrome.

(Last Sunday, the Messenger was able to publish a brief statement of notable accomplishments by Lieutenant Commander Robert Brodie, Jr., of Owensboro, who, on an old naval vessel carefully prepared for a precarious mission, opened up Sebu river in French Morocco for the segment of the American Invasion of North Africa which captured the airdrome at Port Lyautey. Herewith is a graphic account of the exploit transmitted by United Press Correspondent Walter Cronkite from Port Lyautey. It follows:)

By WALTER CRONKITE

This Steve Brodie took a chance, too.

But instead of jumping off a bridge, this Steve Brodie stood on the bridge of a stripped-down old American destroyer and pushed her through the mud of the shallow Sebu river to capture the Port Lyautey airdrome.

Today is the deadline for Lieut. Cmdr. Robert Brodie, Jr., Washington, D. C.–known in the Navy as Steve. He has 122 officers and men under him and their assignment is to drive their destroyer through the big net that guards the mouth of the Sebu river.

Tried Twice

Steve has made two runs for the net, but the French have batteries of 75's on the banks and both times the fire has been so thick that the destroyer has been forced to turn back. But American planes, based on a carrier lying out to sea, need the airdrome and they need it badly. Ground troops are stymied and the whole operation depends on Steve getting up the river and landing a party to attack the airdrome. Lieut. James W. Darroch and six men have gone up to the net in a small boat and weakened it with wire cutters. Now Steve is ready to make his third run.

"We're going to ram the net," he messages Admiral Monroe Kelly, who is waiting on the flagship outside the river mouth.

A few minutes pass and then Brodie messages again: "We're through the net."

Meets Gunfire

Now the destroyer is in the Sebu river and is catching hell from machine gunners and riflemen on both banks.

"We're being fired on and have returned the fire," Steve messages. The destroyers' [sic] guns knock out a machine-gun nest and scare away an antitank battery that has been holding up the American advance from the beach for two days.

The destroyer's keel begins to scrape bottom. A month ago Steve had been ordered to lighten the ship by getting rid of everything except essentials, but the river still is so shallow that the engines threaten to pound through the sides.

Full Speed Ahead

"The engine room called up and said we were turning at near full speed," said Lieut. John Ferguson, executive officer. "I look over the side and we were barely moving. All the time the enemy was shooting at us and we were crawling on our belly through the mud with the old lady threatening to stop for good in the middle of the stream."

The old lady made it though. She ploughed on up to where some troops, tired and hip-deep in mud, were trying to attack the north side of the airfield. Some of them had lost their helmets and guns in the mud and they were getting ready to go to their rubber boats when the old lady sailed into view.

"Hell, men, there's the Navy," one of the soldiers yelled. "If they can do it, we can."

Only One Casualty

The soldiers turned back for another try at attacking the airport. At the same time Steve sent his raiders, headed by Lieut. Quentin Hardige, of Madden, Masss., over the side on cargo nets into tiny rubber boats. Machine-guns opened up and the rubber boats paddled 300 yards through machine-gun fire. On the east side of the river 75's opened up against Steve's destroyer. One shell clipped the aerial and others sprayed shrapnel across the deck.

But the only casualty was Lieut. B. H. Mathers, Jacksonville, Fla., the ship's doctor, who was injured early in the trip up the river. He slipped and sprained his ankle.

Hardige's raiders landed with tommy guns spitting at the defenders of the airport building.

"We didn't lose a man crossing the river," Hardige said later, "and when we hit the opposite bank the Moroccans came out of the airport buildings with their hands up."

Steve Brodie is passing compliments among the crew tonight.

"She's a Raggedy Ann ship and a Raggedy Ann crew," he said, "but we think we helped turn the tide of battle and we're pretty damned proud of it."

BRODIE'S WIFE WAS SURE HE'D DO A GOOD JOB

When Skipper Brodie's wife, who had not seen him since October, was reached at their home, 4800 block forty-seventh St., NW., (Washington, D. C.) she was unaware that the commander had become a hero, but proudly remarked: "I am sure that whatever he did was well done." Commander Brodie graduated from Annapolis in 1927.

The Brodies have two sons, Robert, III, 13½-year-old student at Alice Deal Junior high school, and Reid, 2½. Mrs. Brodie belongs to a real Navy family. She is the former Dixie Plummer Hill, the daughter of Lieut. Cmdr. Patrick Hill, U.S.N., retired, of the 3800 block Cathedral Ave., NW.

Commander Brodie is a son of the late Dr. Robert Brodie and of Mrs. Brodie, of Owensboro, Ky., where he was born December 2, 1904.

Citation:

Clipping from The Owensboro Messenger (Owensboro, Kentucky), December 6th, 1942, page 11. Original article by Walter Cronkite for United Press.

Heroic Feat Of Owensboro Man Revealed In Graphic Account Of African Action

Lt. Cmdr. Robert Brodie, Jr., Pushed Old Destroyer Right Into Morocco to Make Way For Capture of Airdrome.

(Last Sunday, the Messenger was able to publish a brief statement of notable accomplishments by Lieutenant Commander Robert Brodie, Jr., of Owensboro, who, on an old naval vessel carefully prepared for a precarious mission, opened up Sebu river in French Morocco for the segment of the American Invasion of North Africa which captured the airdrome at Port Lyautey. Herewith is a graphic account of the exploit transmitted by United Press Correspondent Walter Cronkite from Port Lyautey. It follows:)

By WALTER CRONKITE

This Steve Brodie took a chance, too.

But instead of jumping off a bridge, this Steve Brodie stood on the bridge of a stripped-down old American destroyer and pushed her through the mud of the shallow Sebu river to capture the Port Lyautey airdrome.

Today is the deadline for Lieut. Cmdr. Robert Brodie, Jr., Washington, D. C.–known in the Navy as Steve. He has 122 officers and men under him and their assignment is to drive their destroyer through the big net that guards the mouth of the Sebu river.

Tried Twice

Steve has made two runs for the net, but the French have batteries of 75's on the banks and both times the fire has been so thick that the destroyer has been forced to turn back. But American planes, based on a carrier lying out to sea, need the airdrome and they need it badly. Ground troops are stymied and the whole operation depends on Steve getting up the river and landing a party to attack the airdrome. Lieut. James W. Darroch and six men have gone up to the net in a small boat and weakened it with wire cutters. Now Steve is ready to make his third run.

"We're going to ram the net," he messages Admiral Monroe Kelly, who is waiting on the flagship outside the river mouth.

A few minutes pass and then Brodie messages again: "We're through the net."

Meets Gunfire

Now the destroyer is in the Sebu river and is catching hell from machine gunners and riflemen on both banks.

"We're being fired on and have returned the fire," Steve messages. The destroyers' [sic] guns knock out a machine-gun nest and scare away an antitank battery that has been holding up the American advance from the beach for two days.

The destroyer's keel begins to scrape bottom. A month ago Steve had been ordered to lighten the ship by getting rid of everything except essentials, but the river still is so shallow that the engines threaten to pound through the sides.

Full Speed Ahead

"The engine room called up and said we were turning at near full speed," said Lieut. John Ferguson, executive officer. "I look over the side and we were barely moving. All the time the enemy was shooting at us and we were crawling on our belly through the mud with the old lady threatening to stop for good in the middle of the stream."

The old lady made it though. She ploughed on up to where some troops, tired and hip-deep in mud, were trying to attack the north side of the airfield. Some of them had lost their helmets and guns in the mud and they were getting ready to go to their rubber boats when the old lady sailed into view.

"Hell, men, there's the Navy," one of the soldiers yelled. "If they can do it, we can."

Only One Casualty

The soldiers turned back for another try at attacking the airport. At the same time Steve sent his raiders, headed by Lieut. Quentin Hardige, of Madden, Masss., over the side on cargo nets into tiny rubber boats. Machine-guns opened up and the rubber boats paddled 300 yards through machine-gun fire. On the east side of the river 75's opened up against Steve's destroyer. One shell clipped the aerial and others sprayed shrapnel across the deck.

But the only casualty was Lieut. B. H. Mathers, Jacksonville, Fla., the ship's doctor, who was injured early in the trip up the river. He slipped and sprained his ankle.

Hardige's raiders landed with tommy guns spitting at the defenders of the airport building.

"We didn't lose a man crossing the river," Hardige said later, "and when we hit the opposite bank the Moroccans came out of the airport buildings with their hands up."

Steve Brodie is passing compliments among the crew tonight.

"She's a Raggedy Ann ship and a Raggedy Ann crew," he said, "but we think we helped turn the tide of battle and we're pretty damned proud of it."

BRODIE'S WIFE WAS SURE HE'D DO A GOOD JOB

When Skipper Brodie's wife, who had not seen him since October, was reached at their home, 4800 block forty-seventh St., NW., (Washington, D. C.) she was unaware that the commander had become a hero, but proudly remarked: "I am sure that whatever he did was well done." Commander Brodie graduated from Annapolis in 1927.

The Brodies have two sons, Robert, III, 13½-year-old student at Alice Deal Junior high school, and Reid, 2½. Mrs. Brodie belongs to a real Navy family. She is the former Dixie Plummer Hill, the daughter of Lieut. Cmdr. Patrick Hill, U.S.N., retired, of the 3800 block Cathedral Ave., NW.

Commander Brodie is a son of the late Dr. Robert Brodie and of Mrs. Brodie, of Owensboro, Ky., where he was born December 2, 1904.

Citation:

Clipping from The Owensboro Messenger (Owensboro, Kentucky), December 6th, 1942, page 11. Original article by Walter Cronkite for United Press.

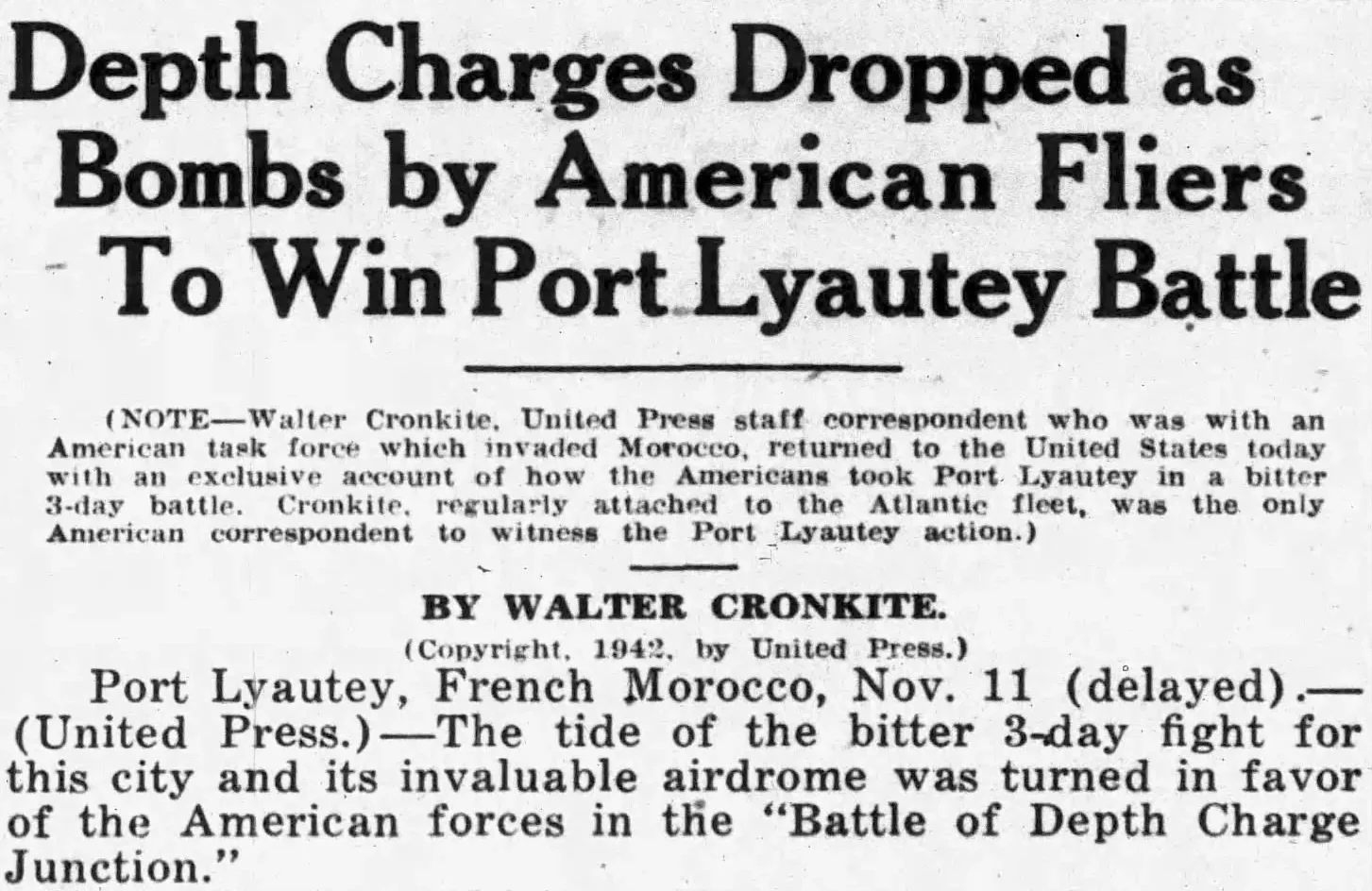

Depth Charges Dropped as Bombs by American Fliers To Win Port Lyautey Battle

(NOTE–Walter Cronkite, United Press staff correspondent who was with an American task force which invaded Morocco, returned to the United States today with an exclusive account of how the Americans took Port Lyautey in a bitter 3-day battle. Cronkite, regularly attached to the Atlantic fleet, was the only American correspondent to witness the Port Lyautey action.)

BY WALTER CRONKITE

(Copyright. 1942, by United Press.)

Port Lyautey, French Morocco, Nov. 11 (delayed). –(United Press.) –The tide of the bitter 3-day fight for this city and its invaluable airdrome was turned in favor of the American forces in the "Battle of Depth Charge Junction."

The junction is a road intersection five miles south of Port Lyautey on the broad highway to Rabat. It was along that road that the French tried to move columns of tanks and motorized troops to reinforce their beleaguered garrison here.

Twice tanks and troops from the crack Moroccan garrison at Rabat–the most decorated single battalion in all Morocco is there–tried to get by the junction and twice they were blasted, decimated and turned around by depth charges used as aerial bombs.

The road was blocked by combination action of slow footed scouting planes, dive bombers, naval shell fire from off shore and American tank columns which rushed down from the northern beachheads to engage the enemy–but it was the scouting planes that led the attack.

They are ponderous craft unequipped for serious fighting or bombing over land, but behind their controls were fealess [sic] aviators. When they spotted the enemy columns moving up the Rabat road, they hastened back out to their ships, refitted their big depth bombs – which carry hundreds of pounds of explosives to blast open the hulls of subrines [sic] – with instantaneous fuses and dove to dangerous low altitudes to lay them squarely on the leaders of the French

Their attacks slowed the columns until, first, naval shell fire could be brought to bear, and, later, dive bombers and the American tanks could join the fray.

Important Part.

Their action was deemed to have played an important part in enabling the combined amphibious forces of the United States army and navy to capture today this colonial city of 17,000, mostly Europeans, and its modern seaplane and landplane airdrome.

Fear of axis intervention by planes made imperative capture of the Port Lyautey airdrome, northernmost of the American objectives in Morocco, but the French Foreign Legion and crack Moroccan rifle and cavalry battalions fought viciously against the allied occupation and the American forces had to blast their way inland with all the weapons at their command.

They went ashore in the predawn dark of Sunday morning. Many already were on the beaches and the landing boats were shuttling back out to the transports at sea, for the second load before the French opened fire.

The 10 miles from the beach back to the city represented French "defense in depth" carried to its ultimate. Anti-aircraft batteries filled the woods and marshes and grouces of bushes and mobile 75 batteries surround them. The mobility of the 75's proved the most treacherous problem for the Americans. The batteries laid down a short barrage, then moved to another spot before American spotting planes or scouting parties could plot their positions.

On Beach Two Days.

For two days the American forces were stuck on the beach. A withering blanket of fire proved impenetrable until navy dive-bombers took the Kasba city-fortress under fire and silenced it with one hour of well-laid eggs.

While the Kasba held out, other American forces, landed above and below it, had managed some penetration. Tanks landed on the beach to the north moved overland several miles to stifle native Morroccan [sic] resistance but they were prevented from coming in behind the Kasba by the Sebu river. Troops on the beaches to the south of the Kasba were able to offer little assistance to the main central force. They were engaged, instead, in blocking the road from Rabat, 20 miles to the south, from which the French tried twice to send assistance to the beleaguered garrison at Port Lyautey.

American mastery of the air–gained the first day despite gallant resistance from the outnumbered French fighters based here–and the inability of the French to send reinforcements along either the road from Meknes or Rabat finally wore down the French.

Citation:

Clipping from The Rock Island Argus (Rock Island, Illinois), November 27th, 1942, page 10. Original article by Walter Cronkite for United Press.

Revenge Day Draws Nigh

North Africa Anti-Axis Ready to Wreak Vengeance

By WALTER CRONKITE

United Press Staff Correspondent

PORT LYAUTEY, French Morocco.–A baby-faced boy of 18, bundled into an overcoat which concealed the French Foreign Legion uniform that would have branded him a deserter, offered me a list of Frenchmen.

"We want you to shoot them as soon as possible," he explained.

Those on the list were pro-Vichy Frenchmen. They had been in the minority, but for two years they had matters their own way and ruled with an iron hand under Nazi guidance. The festering bitterness which has arisen between them and pro-Allied Frenchmen is a baffling problem for the ablest diplomats with the American occupation forces in French West Africa.

Before I encountered that boy I had been sitting at a sidewalk café filled with laughing, gleeful Frenchmen. It was the "pro-Allied" café of Port Lyautey. Across the street was the "pro-Vichy" almost empty.

"We have had to whisper just as they whisper in Germany and France," an Allied sympathizer told me. He was wearing the tri-color badge his friends had broken out when the American troops arrived.

"We've waited two long years for you to come," he said, "so we could talk out loud once more."

There were sullen looks from the pro-Vichy cafe. I felt uncomfortable sitting there, as though I had stepped into a family feud. So I left, and then I met the boy who wanted to kill all pro-Vichyites.

He stopped me to inquire the way to American army headquarters. He answered my quizzical look by opening his overcoat just a bit to reveal a glimpse of the bright uniform of the Foreign Legion.

"I have waited two years for a chance to escape so I could fight with the democracies again," the boy said. "When the Americans came I ran away from my regiment at Meknes and walked 80 miles here. Now will you tell me where the Americans are?"

HAD TO BE RETURNED

I told him, but I knew he faced a rude shock. The American forces had received scores of French Legionnaires – Poles, Russians, Czechs and others – who had similar ideas. But the Americans had no facilities to care for them and, technically, now that the armistice delegates were meeting in Algiers, they were under obligation to return these lads to their troops.

Another problem is what to do with the merchants of Morocco who want to do a little "business as usual" with the help of American merchandise and American money.

There are a score of first-class shops in this modern colonial outpost of 17,000 persons, some fancier than those in an American city of similar size. From the hardware merchant to the beauty operator, they told the same story to the first Americans to arrive.

"Now if America will just send us something to sell," they said.

RECEIVED LITTLE GOODS

They pointed to empty shelves. Virtually isolated since the fall of France, little merchandise had reached them.

The population would like something to buy. They have a fair amount of staples like meat, fish, cereals and the like, which they can produce themselves, but they need clothing, other foodstuffs and gasoline for their immobilized machines.

The ravages of idleness are visible throughout Port Lyautey. Its modern docks and warehouses once handled thousands of tons of shipping annually, sending millions of dollars worth of merchandise inland to Meknes and Fez.

But when the Americans came they found the machinery of the dock cranes rusted. Ships had been up the river for months or years either interned or hiding.

The merchants are clamoring for American goods to speed up the slowing commercial heart of West Africa.

Citation:

Clipping from Saskatoon Star-Phoenix (Saskatoon, Saskatchewan, Canada), December 24th, 1942, page 7. Original article by Walter Cronkite for United Press.

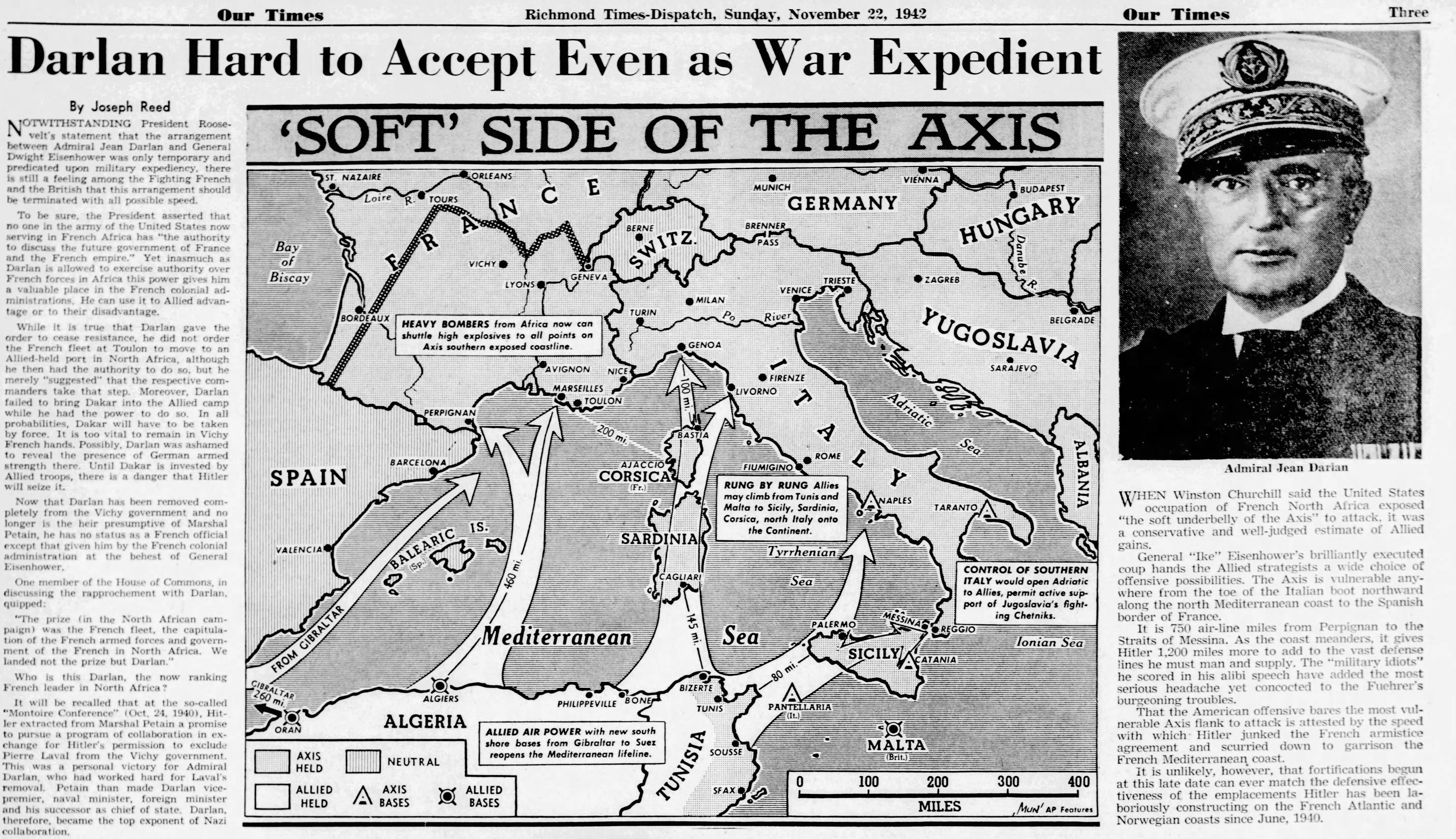

The Deal with Darlan

The "Deal with Darlan", as it came to be known in American and British press, was controversial at the time. Darlan was considered a Fascist by the general public in the US and Britain, due to his role in the Vichy government. The armistice deal had made Darlan the High Commissioner of France in Africa, the political leader of French Africa, a high position for someone who had been cooperating with the Axis until this point.

This article highlights the mixed reception of the armistice that concluded Operation Torch. Securing the cooperation of French North Africa had opened many potential lines of attack against the Axis, particularly Italy, and ended the battle with less bloodshed than a protracted campaign across Morocco and Algeria. But Darlan's participation in the Vichy government and collaboration with the Nazi regime was still difficult for the public to accept.

The controversy surrounding Darlan was cut short the following month. Darlan was assassinated by a French man and former resistance fighter on December 24th, 1942. The assassination was apparently in retaliation for his participation in the Vichy government and failure to overturn many of its policies in North Africa after the armistice. With Darlan gone, Giraud - who had been chosen as Commander-in-Chief after the cease fire on November 11th - succeeded him as the political leader of French Africa.

A transcript of the shown newspaper article follows. Keep in mind that the claims in this article are based on information available in November 1942. Not all reporting at this time was accurate due to wartime secrecy surrounding these events but did reflect some common public views from the time period.

Darlan Hard to Accept Even as War Expedient

By Joseph Reed

NOTWITHSTANDING President Roosevelt's statement that the arrangement between Admiral Jean Darlan and General Dwight Eisenhower was only temporary and predicated upon military expediency, there is still a feeling among the Fighting French and the British that this arrangement should be terminated with all possible speed.

To be sure, the President asserted that no one in the army of the United States now serving in French Africa has "the authority to discuss the future government of France and the French empire." Yet inasmuch as Darlan is allowed to exercise authority over French forces in Africa this power gives him a valuable place in the French colonial administrations. He can use it to Allied advantage or to their disadvantage.

While it is true that Darlan gave the order to cease resistance, he did not order the French fleet at Toulon to move to an Allied-held port in North Africa, although he then had the authority to do so, but he merely "suggested" that the respective commanders take that step. Moreover, Darlan failed to bring Dakar into the Allied camp while he had the power to do so. In all probabilities, Dakar will have to be taken by force. It is too vital to remain in Vichy French hands. Possibly, Darlan was ashamed to reveal the presence of German armed strength there. Until Dakar is invested by Allied troops, there is a danger that Hitler will seize it.

Now that Darlan has been removed completely from the Vichy government and no longer is the heir presumptive of Marshal Petain, he has no status as a French official except that given him by the French colonial administration at the behest of General Eisenhower.

One member of the House of Commons, in discussing the rapprochement with Darlan, quipped:

"The prive (in the North African campaign) was the French fleet, the capitulation of the French armed forces and government of the French in North Africa. We landed not the prize but Darlan."

Who is this Darlan, the now ranking French leader in North Africa?

It will be recalled that at the so-called "Montoire Conference" (Oct. 24, 1940), Hitler extracted from Marshal Petain a promise to pursue a program of collaboration exchange for Hitler's permission to exclude Pierre Laval from the Vichy government. This was a personal victory for Admiral Darlan, who had worked hard Laval's removal. Petain than [sic] made Darlan vice-premier, naval minister, foreign minister and his successor as chief of state. Darlan, therefore, became the top exponent of Nazi collaboration.

WHEN Winston Churchill said the United States occupation of French North Africa exposed "the soft underbelly of the Axis" to attack, it was a conservative and well-judged estimate of Allied gains.

General "Ike" Eisenhower's brilliantly executed coup hands the Allied strategists a wide choice of offensive possibilities. The Axis is vulnerable anywhere from the toe of the Italian boot northward along the north Mediterranean coast to the Spanish border of France.

It is 750 air-line miles from Perpignan to the Straits of Messina. As the coast meanders, it gives Hitler 1,200 miles more to add to the vast defense lines he must man and supply. The "military idiots" he scored in his alibi speech have added the most serious headache yet concocted to the Fuehrer's burgeoning troubles.

That the American offensive bares the most vulnerable Axis flank to attack is attested by the speed with which Hitler junked the French armistice agreement and scurried down to garrison the French Mediterranean coast.

It is unlikely, however, that fortifications begun at this late date can ever match the defensive effectiveness of the emplacements Hitler has been laboriously constructing on the French Atlantic and Norwegian coasts since June, 1940.

Citation:

Clipping from the Richmond Times-Dispatch (Richmond, Virginia), November 22nd, 1942, page 55.

Thanks for reading!

This exhibit has been produced in cooperation with Professor Jonathan Rayner of the University of Sheffield, UK. Thank you to The University of Sheffield Library Special Collections, National Archives & Records Administration, Naval History & Heritage Command, and Texas Parks & Wildlife Department for providing most of the images for this exhibit.